The Taliban have started their spring offensive of 2016, a year in which the coordination group charged with bringing peace to the country, perhaps ironically, has made its strongest push for resolution. The Afghan government has responded by pledging to ramp up security operations in kind. All this would appear to bode ill for the peace prospects of a country still in the throes of a 14-year war. But there are also some reasons for optimism. Many countries have a vested interest in securing Afghanistan, placed as it is to link the regions surrounding it. That is not to say peace will necessarily prevail, but it is to say that the future of Afghanistan, as with all countries, will be determined by the convergence of domestic politics, international politics and geopolitics.

Analysis

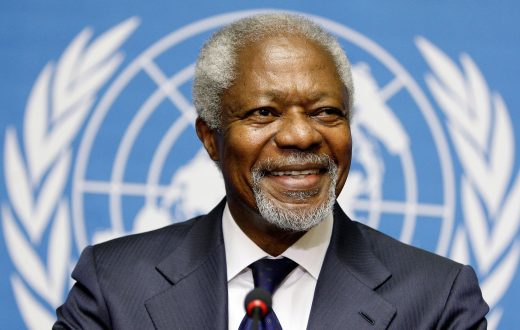

Four key developments have emerged in Afghanistan over the past few weeks, developments that bear directly on the future of the embattled nation. First, representatives from 14 countries, including India, Pakistan, China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and the United States, have gathered in New Delhi for the Heart of Asia Conference-Istanbul Process, which has convened annually since 2011 to promote peace in Afghanistan. In addition to mapping out a blueprint to end the war in Afghanistan, the delegates will discuss funding — the country’s largest source of income — as well as reconstruction and regional infrastructure development. That such a wide range of states has convened to discuss Afghanistan speaks to the country’s geopolitical significance, both as a hotbed of transnational extremism that still threatens regional stability and as a highly strategic energy bridge that promises to connect the Middle East, Central Asia, South Asia and China.

The second key development was the launch of the Taliban’s spring offensive on April 12. The opening salvo — a suicide attack in Kabul on April 19 that killed 64 people — was the deadliest of its kind in five years. Although the spring offensive is an annual event, this year’s is a bit more significant than usual because of its timing. In 2016, the four members of the Quadrilateral Coordination Group — Afghanistan, Pakistan, China and the United States — have made the strongest push for peace talks since the war began in 2001. In addition, the government in Kabul is politically vulnerable, battling corruption, unpopularity and economic stagnation. The Taliban may be trying to take advantage of this weakened position. After the April 19 attack, the militant group released a statement saying they regretted the death of innocent bystanders, claiming they were only targeting government officials. Such a statement is probably intended to broaden the group’s support as it plans its next political move.

Third, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani delivered a speech to a rare joint session of the National Assembly on April 25 outlining a change in strategy. Whereas Ghani had previously prioritized negotiations with the Taliban, he now says he will ramp up attacks against the group as part of a new five-year war strategy to be finalized at NATO’s Warsaw Summit in July. Of course, a deteriorating security situation, an emboldened insurgency and a faltering base of political support likely informed Ghani’s decision. (Many Afghans, in fact, blame him for the country’s security and economic woes, a perception he is eager to reshape.) Hence some of the criticism he levied against Pakistan in his April 25 speech, which lambasted the country many have accused him of accommodating. Ultimately, Ghani wants to position Afghanistan as a cause still worth funding for ahead of two major donor conferences this year, including the Warsaw Summit and the Brussels conference on Afghanistan in October.

Fourth, a three-member Taliban delegation from the organization’s political office in Qatar arrived in Pakistan on April 27 to explore negotiations. While the meeting should be seen as another precursor to actual peace talks, it is significant because it demonstrates Pakistan’s continued leverage over the organization, highlighting the centrality of Islamabad’s role in the process of conflict resolution. The delegation’s visit, moreover, suggests that a negotiated end to the war is possible, albeit fraught and complicated. Notably, some see the visit as a jab at Ghani, who has said he does not expect Pakistan to bring the Taliban to the negotiating table.

There is, of course, a hint of irony in the timing of these four developments: The international community is trying to peacefully resolve a conflict whose participants have both recently pledged to escalate their attacks. The success of either side will depend less on any one factor than on the confluence of factors that continue to challenge Afghanistan.