Even though Bulgaria is one of the oldest country in Europe, it has almost all its history be under foreign control. Three Empires (Byzantine,Ottoman and Soviet Union) have ruled the small country. Still the country despite its key Geographic location has always played a very important role in the geopolitics of the Balkans, usually being the HeavyWeight. Despite that fact , Bulgaria has never play any important role in the European Union. Still the country has a high potential and was a key country in the Soviet Union, even being called the” Silicon Valley” of the USSR because of the high numbers of engineers.

In the past, Bulgaria worked to protect its heartland in the Danubian Plain, south of the Danube River and north of the Balkan Mountains. When nearby Constantinople (or its successor, Istanbul) was weak or friendly, Bulgaria focused benefitting from the Thracian Plain’s fertility and its position as a communication corridor between Europe and Asia. With the 19th century ascendance of both the European powers and the Russian Empire, Bulgaria found itself wedged in the middle and needing to balance both sides.

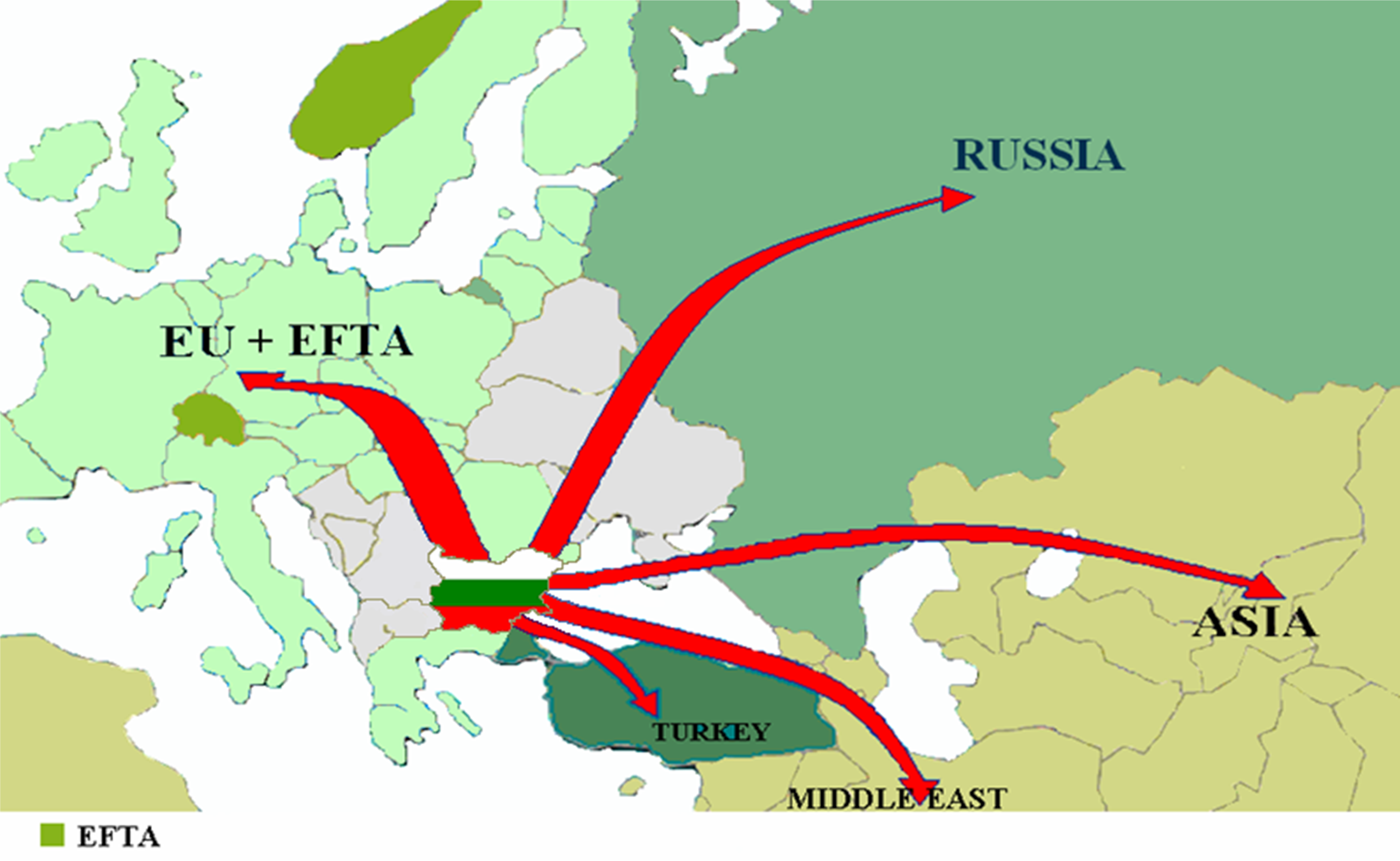

Today, Bulgaria is shielded by its membership in NATO as well as in the European Union. Under this protection, Sofia is building up its economic and military power. But both of these blocs are in precarious positions. In addition, Bulgaria’s balance between Russia and Europe is delicate and Turkey is experiencing a resurgence. These factors mean that Bulgaria may once again become subject to foreign interests.

Analysis

Bulgaria is located at the southeastern end of the Balkan Peninsula, the tapering wedge of land that connects Europe with Asia at the Bosphorus Strait. “Balkan” is a Turkish word meaning “wooded mountain chain,” an apt description for much of the territory. In the west, the clustered mountains extend all the way to the Adriatic Sea, where sheer hilly ramparts line much of the coast. In the eastern Balkans, where Bulgaria is located, the terrain is less harsh.

Bulgaria’s northern border mostly follows the great Danube River as it makes its final descent to the Black Sea. The river is not enough of a barrier to discourage a determined invader (it has failed to do so to many times), but it has served as a clear boundary marker for modern Bulgaria as well as for the Byzantines and Romans before. The Wallachian Plain, on the Danube’s northern bank, has never supported a polity strong enough to seriously threaten Bulgaria. However, greater powers from further afield have invaded from this direction, including Russia and Germany. The Black Sea lies on the country’s eastern flank, where the coastline is less rugged than that of the Adriatic. This coast has always been the focus of a substantial naval presence by greater powers (the Byzantines and later the Russians). As a result, Bulgarians have rarely tested their maritime boundaries.

To Bulgaria’s southeast, is the country’s greatest threat: a city that has had many names but was called Constantinople throughout much of modern history. Bulgaria’s southeastern border slices across the Thracian Plain, a horseman’s paradise which extends down to that city and up into the heart of modern Bulgaria’s territory. Finally, the Rhodope and Balkan mountain ranges are along the southern and western borders and, beyond them, the Western Balkans.

The interior of the country is dominated by the jutting extension of the Balkan Mountains, which cleaves the country in two as it traverses from west to east, providing a barrier that becomes less formidable as it approaches the Black Sea. North of the mountain wall is the highly fertile Danubian Plain, south of it the Thracian Plain. How the country’s residents use this mountain barrier has been shaped by — and has shaped — its relationship with the outside world and particularly with Constantinople.

Bulgaria’s core population center has historically been situated in one of two ways, depending on the strength of foreign powers. When the threat of invasion is low, Bulgaria can act as a connection between East and West; when the threat is high, Bulgaria’s center of power tends to shift to the more protected region north of the Balkan Mountains and south of the Danube River. Under the Roman Empire, Bulgaria took on the first configuration, acting as an important thoroughfare between Europe and Asia. During this time, Serdica and Philippopolis, today’s Sofia and Plovdiv, were key outposts on the Via Militaris, the old Roman road, which stretched from Belgrade south to Constantinople. The cities grew rich on the trade that passed through them.

But this setup becomes problematic when Constantinople is in hostile and powerful hands — as it was when the Bulgar tribe first settled the area. The Bulgars had previously lived in the area of modern Ukraine and Russia on the northeast shores of the Black Sea. But in A.D. 681, another Central Asian tribe, the Khazars, drove them into what is now Bulgaria. Crossing the Danube brought the Bulgars into conflict with the Byzantine Empire based in Constantinople. When the Bulgars settled in the area, they mixed with the resident Slavs who had also recently migrated. Because of the powerful status of Constantinople, the group adopted Bulgaria’s second settlement pattern and three capital cities emerged at different points south of the Danube. While not as favorably placed for trade, the Danubian Plain can sustain a sizable population. The mountain barrier also provided plenty of opportunities for ambushing any approaching Byzantine armies. In fact, the mountains are particularly suited to the purpose: The steep southern face gives an advantage to the northern defender.

Constantinople’s Long Shadow

Despite the antagonistic relationship and threat Constantinople’s proximity creates, Bulgaria’s place on the Danubian and Thracian plains still give it a unique advantage to create a strong power base. Typically, flat land facilitates the formation of stronger states and fertile river plains tend to have greater capacity to support large cities. Bulgaria has both, and its mountainous regions provide the military with excellent training grounds to prepare for Balkan conquest. Thus, when Constantinople is weak and under attack by others, such as Crusader and Muslim armies, Bulgaria has the ability to project its power westward into modern Macedonia, southern Serbia, northern Greece and even as far as Albania on the Adriatic coast. It managed to do this twice, once during the First Bulgarian Empire from A.D. 681 to A.D. 1018 and from A.D. 1185 to A.D. 1396 under the Second Bulgarian Empire. Expansion is attractive for Bulgaria because with increased size comes increased protection for its heartland.

But the opportunity to expand does not arise often. The fragmented Balkans is a crossing point that has historically been situated near great centers of power — first Constantinople and later Russia and Europe. And because much larger powers surround it, the country has spent 694 years of its 1335-year existence under foreign rule (649 under Constantinople and 45 under Moscow.) Generally, domination has not been positive for Bulgaria and has arrested its development.

Facing a Changed World

After five centuries of Ottoman subjugation, Bulgaria regained independence in 1878. It emerged as an ambitious new nation, although one that was not officially recognized until 1908. The Ottomans had been in decline for centuries, and Bulgaria sensed a rare opportunity to once again spread its influence westward. As a result, the country adopted the Roman configuration for the rejuvenated state, choosing as its capital the small city of Sofia in the western mountains. The city’s location on a high plain acted as a central point from which a Bulgarian and Macedonian empire could be governed and from which the Thracian Plain and the ancient city of Plovdiv could open. Railways were built around Sofia, and a new port was created at Burgas (today, Bulgaria’s fourth largest city) ready to accept goods from across the country and from the sea.

But the empire that Sofia was meant to govern never emerged. The world had changed and Turkish weakness no longer automatically led to Bulgarian opportunity. Bulgaria was now caught up in a global game and the Balkan countries were chess pieces. During the first 40 years of its independent existence, Bulgaria fought losing battles to regain former territories to its west and southwest, predominantly in modern Macedonia. At different points, its adversaries in the struggles included Serbia, Greece, Turkey, various European powers and (during both world wars) Russia. Bulgaria invariably came out on the losing side of these confrontations, including in World War II, which it was drawn into without having any great desire to take part. At the war’s end, Bulgaria was once again under foreign rule — that of Russia.

Soviet Repercussions

Russia’s rule touched every aspect of Bulgarian society — social, political and cultural — but perhaps the most lasting effects were economic. Between 1878 and 1945, Bulgaria’s attempts to modernize achieved mixed results. The increased importance of Sofia, which is isolated in the mountains and therefore relatively inefficient, combined with a lack of initial investment and various wars to slow Bulgaria’s development. By 1944, the country was still poor with a largely agrarian economy, although periods of rapid growth had helped it along toward the end of the 19th century.

Soviet-inspired attempts to rapidly modernize led to the expropriation of land and giant industrial projects, increasing Bulgaria’s production, as was often the case in Soviet states. But it also resulted in uncompetitive production techniques and inefficiencies compared with Western states. Bulgaria became the premier electronics producer for the closed Soviet trade bloc, the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon), and at one point was producing 40 percent of the Eastern Bloc’s computers.

The Bulgarian export machine was coming to rely more and more on Western inputs, however, and these were becoming harder to pay for with the weakening Soviet currency. The shortcomings of the system became unavoidably evident with the fall of the Soviet Union. Bulgarian exports plummeted, and inflation and unemployment soared. Even more damaging was the exodus of people that resulted from the opening of the borders. In 1989, Bulgaria had 9 million people and by 2015 that number had plummeted to 7.11 million.

However, after the 1990s the economy began to recover, galvanized by the new prospect in 2007 of joining the European Union. Before its Soviet days, Bulgaria had tight economic ties with Europe (first with the United Kingdom and France and later with Italy and Germany), and once the Comecon network collapsed, it seemed an obvious step to rekindle them.

Newly European

During the 2000s, the newly created euro area was awash in investment capital, some of which flooded into Bulgaria, driving its current account deficit of net foreign assets down as far as -24.3 percent of GDP in 2007. Unsurprisingly, the economy boomed, averaging more than 5 percent growth a year between 2000 and 2008. While the 2008 economic crash took some of the shine off that growth, real GDP per capita today is double what it was in 2000. (Though a declining population during this time does slightly exaggerate the numbers.) This success is in sharp contrast to the plight of Greece, Bulgaria’s Balkan neighbor. Though Greece began with a higher GDP that climbed faster than Bulgaria’s (and still has a higher GDP), it has since lost much of what it gained in the first decade of this century, while Bulgaria has maintained many of its gains.

Bulgaria has also had success in its electronics and information technology sectors, which have recently been showing signs of recovery following the fall of the Soviet Union. In the last 10 years, exports of electrical equipment have increased by 3.5 times, boosting these goods from Bulgaria’s seventh largest export to its second. Moreover, with Europe’s most competitive labor costs and with Internet speeds in the global top 20, Bulgaria has become a hub for IT outsourcing. Once referred to as the “Silicon Valley of the Soviet Union,” Bulgaria is now being called the “Silicon Valley of Eastern Europe.” But the economic outlook is not all positive.

Transparency International recently published a survey that ranked Bulgaria the European Union’s most corrupt member, another lingering consequence of Soviet rule. Joining the European Union has also fueled emigration, considering it is now easier for Bulgarians to leave the country in search of better wages elsewhere. Today, Bulgaria, which has already lost 20 percent of its population since 1990, is the country with the worst demographic outlook in the world; the U.N. predicts a further 27.9 percent population drop by 2050.

The Big Picture

Bulgaria has spent much of its history either menacing the area to its west, or itself being menaced by larger states all around. But accession to the European Union and NATO (which it joined in 2004) appear to have placed these geopolitical trends on hold. Turkey is relatively unthreatening, as it has been since Bulgaria escaped its influence in 1878, and Russia is no longer projecting power like it did when it was the Soviet Union.

Time also appears to have isolated Bulgarian ideas of westward expansion to fringe political parties. Bulgaria and Macedonia still have spats, for example over the latter’s potential EU accession, but the relationship is not explosive. Balkan countries no longer view Bulgaria as a threat, as it was in the first half of the last century. It would seem then, drawing from recent growth, that the immediate future should be relatively stable.

However, the long-term picture is somewhat gloomier. Bulgaria’s demographic outlook is likely to undermine its aspirations for growth in the coming decades and will leave the country weaker than its peers. Meanwhile, Bulgaria’s imperative to balance great powers to avoid being dominated has over time proved extremely challenging to carry out. The latest attempt, aligning with Europe through the European Union while also maintaining relations with Russia, has been successful, but the sustainability of the tactic is questionable. The European Union has provided stability, but the flaws in its model are becoming apparent. If the European project unravels, Bulgaria will fully rely on NATO for its security. NATO was an alliance created to counter a Soviet and then Russian threat — meaning that if the threat diminished enough, the security bloc could become obsolete. It is not hard to imagine a world in the next few decades in which Bulgaria is stripped of both its EU and NATO protections.

A weakened Bulgaria without protections could theoretically be fine if it existed in a region without threats. But that has never been the case. In the middle of the Balkans, the fragmented crossroads of Eurasia, Bulgaria has never lacked for attention from foreign powers. For most of Bulgaria’s 13 centuries in existence, Turkey has defined the country’s position. During the last two centuries, Turkey’s attention has been diverted elsewhere, but it cannot be assumed that it will remain so indefinitely. The country has been strengthening, and if and when Turkey does resurge, Bulgaria will likely be under determined pressure to yield to Constantinople yet again.