Summary

Three and a half months after regional elections concluded, the Catalan Parliament finally appointed a government Jan. 10. The new regional president, Carles Puigdemont, promised that his administration would proceed with a plan to declare independence from Spain within 18 months. But the new government will encounter the same problems that have undermined previous secession campaigns.

Analysis

Puigdemont’s appointment was the result of long and difficult negotiations between pro-independence forces. Together for Yes, a coalition of conservative and center-left parties that supports secession, won the regional elections Sept. 27 but failed to secure enough seats in the regional parliament to appoint a government. Forced to seek a partner, Together for Yes turned to the Popular Unity Candidacy (CUP), a small left-wing party that supports independence but is critical of Catalonia’s political establishment. The CUP’s refusal to support another term for Catalonia’s former president, Artur Mas, impeded negotiations for months. They finally agreed on Puigdemont, the mayor of Girona and a member of Mas’ party.

The agreement has exposed the fragility of the pro-secession camp. Some members of Together for Yes believe their party has made too many concessions to the CUP and will probably resist compromise in the future. More important, Together for Yes and the CUP have different views on economic matters and the handling of the Catalan state. Although the CUP will not be a formal member of the Catalan government, friction between it and Together for Yes could re-emerge and again threaten the secession process.

Madrid’s Many Options

According to a roadmap to independence presented in November, Catalonia will begin creating the institutions and structures of an independent state over the next 18 months. This involves the creation of new ministries and a central bank and the drafting of a constitution. Catalonia will then hold a referendum to ratify the constitution once it is ready, according to the roadmap. If the secessionists have their way, Catalonia will become independent in early to mid-2017.

Spain has many options to stop the process. The most drastic would be to suspend Catalonia’s regional autonomy and take direct control of the Catalan regional government itself. This option is nothing short of a last resort because it would aggravate tension with Catalonia and call into question the entire system of regional autonomies created in the late 1970s.

Instead, Madrid will gradually put the squeeze on Catalonia, which relies on regional funds controlled by Madrid. The Spanish government also will rely on the Constitutional Court, which last year gained the authority to introduce penal and financial sanctions on regional governments that violate the Spanish Constitution. So far, most of Catalonia’s steps toward secession have been symbolic, such as the approval of a “solemn proclamation” of the beginning of the process of independence. These measures are inconsequential. But if Catalonia takes steps that change its relationship with Madrid, the Constitutional Court could impose fines or even order the arrest of Catalan politicians.

Catalonia’s National Impact

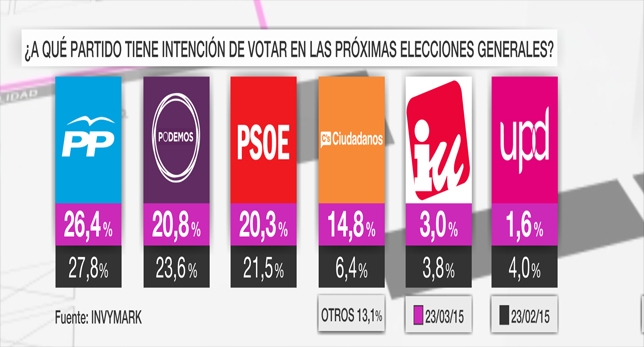

Even if Madrid can resist Catalonia’s secessionist push, some significant problems remain. To begin with, a caretaker government is in charge in Madrid because the general elections in December produced a hung parliament. The Spanish parliament will restart sessions the week of Jan. 18 and, under King Felipe’s supervision, will begin formal negotiations to create a government. The formation of a government in Catalonia probably will add a sense of urgency to this process, but Spain’s four largest parties (the Popular Party, Ciudadanos, the Socialist Party and Podemos) still have to overcome important ideological and strategic differences before they can agree on a government.

Acting Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy’s conservative Popular Party is seeking support from the centrist Ciudadanos and the center-left Socialist Party to remain in power. Even if these parties do not actively support the Popular Party, if they both abstain during a vote in parliament, the Popular Party could form a minority government. Ciudadanos said it could help the Popular Party get reappointed, but the Socialist Party said it would not.

The appointment of a Catalan government lowers the likelihood of an alliance between the Socialist Party and left-wing Podemos because Podemos supports an independence referendum in Catalonia and the Socialists do not. In fact, one of the reasons the Socialists are reluctant to support Rajoy’s Popular Party is the fear that doing so would strengthen the anti-establishment Podemos because voters would see Podemos as the only force opposing the Popular Party.

The Socialist Party said Jan. 11 it would support any measure to protect Spain’s territorial unity but insisted it would not enter a grand coalition with the Popular Party. However, the Socialists will encounter greater political pressure to allow the Popular Party — their traditional rival — to form a government, or even to be a part of a Popular Party-led government. Catalonia’s renewed push for independence, along with King Felipe’s intervention in talks to form a government in Madrid, could soften the Socialists’ resistance to a new government led by the Popular Party.

The second problem related to Catalonia’s push for independence is whether the rebel government in Barcelona will respect any decisions by the Constitutional Court and whether Madrid will use security forces to enforce court decisions. Madrid hopes that internal tensions, financial pressure and legal threats will cause the Catalan government to collapse. Stratfor believes this is the most likely scenario. But should Catalan authorities ignore the rulings by the Constitutional Court, Catalan police could be given the order to arrest local politicians.

In the past, Catalan police have said they would respect the chain of command and obey any orders given by the Spanish court. However, the use of security forces against Catalan officials probably would lead to social unrest; almost half the electorate in Catalonia voted for pro-independence parties and could be moved to protest the use of police against Catalan elected officials. As a result, Spanish authorities will continue to follow a gradual and cautious strategy when dealing with Catalonia.