In autumn 2013, China’s president Xi Jinping, announced the One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative. OBOR seeks to rebuild the historical Silk Road—which connected China to Europe during the Han Dynasty. Mr. Jinping announced an intercontinental megaproject comprising of the land based ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ and the ‘Maritime Silk Road of the 21st Century’. (LSE, 2017)

The program is an estimated $5 trillion infrastructure spending spree that spans over more than 60 countries. Together, the 64 nations plus China account for 62% of the world’s population and 30% of the global economic output. (Huang, 2017)

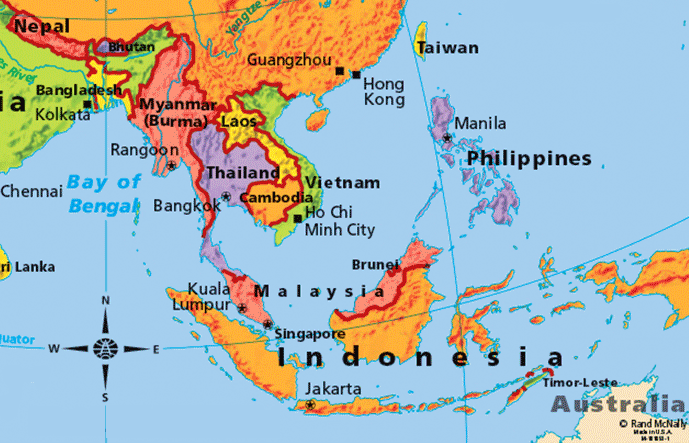

The Silk Road Economic Belt will link China to Europe through Central Asia and Russia; it will connect China with the Middle East through Central Asia; and bring together China and Southeast Asia, South Asia and the Indian Ocean.

The twenty-first-century Maritime Silk Road will focus on using Chinese coastal ports to link China with Europe through the South China Sea and Indian Ocean, as well as connect China with the South Pacific Ocean through the South China Sea. Along these routes, six international economic cooperation corridors will be built. (Shah, 2016) Building transport and information infrastructure that will foster the development of energy and industrial economic zone along these economic corridors. Everything from roads, to bridges, gas pipelines, ports, railways, and power plants. And along this process, foster growth and develop the regions along its way. OBOR will enable the realization of such growth, providing alternative sources of funding to traditional public finance. (LSE, 2017)

The ambitious initiative certainly serves a number of Chinese diplomacy functions. It is meant to help China overcome its growth decrease, through the export of many of its companies abroad. The export of China’s overcapacity in infrastructure building, would turn this problem into an opportunity. Except its economic functions, OBOR has important geopolitical goals. Beijing is seeking to expand its sphere of influence throughout the region, as China becomes a competing superpower to the United States of America. (Shah, 2016)

OBOR and China’s Foreign Policy:

Since China transitioned its leadership to Xi Jinping in November 2012, there has been a significant change in the Chinese strategy of positioning itself in the world and dealing with foreign policy in general. Under this new leadership, Beijing has changed Deng Xiaoping’s former principle of “keeping a low profile” is being replaced by a new Xi Jinping paradigm of move towards ‘striving for achievement’ (fen fa you wei). In order to support and achieve the goals of this new foreign policy paradigm of recentering China as a main international great power, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) initiated a series of megaprojects in China and abroad financed through Chinese owned financial structures. One Belt One Road OBOR is China’s most ambitious initiative. (YAĞCI, 2016) The main official goals of the project according the CCP, is to improve “peace, development, cooperation and mutual benefit” and that the initiative is “designed to uphold the global free trade regime and the open world economy in the spirit of open regional cooperation”. The OBOR document also stated that it “will enable China to further expand and deepen its opening-up, and to strengthen its mutually beneficial cooperation with countries in Asia, Europe and Africa, and the rest of the world”. (Shaohui, 2015) These official statements make this project perfectly fit in Xi Jinping’s Foreign policy aspirations. Through this project among others, China is pursuing its goal of becoming a new global power. By providing a positive leadership to developing countries and increasing their dependency on China. As a parallel, China created some financial development national and international institutions like the Asian Infrastructure and

Investment Bank (AIIB), The New BRICS Development Bank (NBDB). The AIIB will be the main structure to finance OBOR. Which means it will loan billions of dollars to other countries and in that sense play a role of competitor to their Western aquivalents – IMF and World Bank. Although the Chinese banks have a totally different approach on international economics that collide with the Bretton woods institutions in various fields. OBOR has for aim to connect 3 continents and more than 60 countries via roads, railways, and bridges. This will take a long time to complete and for a country with numerous economic challenges, it represents a test to see if a China is capable of such a megaproject. If it proves to be successful in the long run it could change the way the West and especially the US will be portrayed in the world. However, even the mere proposal of this project officializes China’s aspirations of assuming a new role in the global political and economical arena. (YAĞCI, 2016)

China’s grand strategy for OBOR:

International Cooperation:

In China’s OBOR project, the Chines Communist Party puts a major focus on the idea of cooperation between countries. And the image that China’s goal is to boost trade in the countries in development where the route is passing through, in order to help them and China develop their economies.

One of the ways through which it seeks to achieve this goal, is by cooperating within the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) where for now Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan Armenia—and China are part of. On 29 May 2014, Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan signed the ‘EEU Treaty’ in Astana, Kazakhstan. Armenia joined in 2015. The medium-term goal is realize the free flow of goods, services, capital and labor between member countries by 2025, and, ultimately, to create a union similar to the EU. The main reasons for this cooperation framework is that the construction of the new Silk Road requires China to work with Russia and Central and West Asian countries, because these are part of the most important areas for the silk road route. The five countries of the EEU are therefore pivotal to extending the Silk Road Economic Belt westward and northward. Moreover, countries like Kazakhstan, Belarus and especially Russia have important resources like oil, natural gas but also water and agriculture, which are key to the success of OBOR. The EEU also provides a good structure for Sino-Russian relations. They are able to work bilaterally on economic integration that is beneficial for both states, without having to deal with sensitive political issues that may divide them. A regional economic plan like the one of the EEU will enhance the competitiveness of all the participating states, similar to the economic phenomenon that was achieved through the EU for Europe. China understands that this kind of cooperation will be key in achieving their foreign policy goals in general, and OBOR in particular. We’ve seen a rise of FDI by China to the EEU from only $97 million in 2003 to $22.8 billion in 2015—an increase of 235 times. (Biliang Hu, 2017)

Financial Cooperation:

For the realization of the project, China has announced the ‘pillars’ of OBOR: policy communication, road connectivity, unimpeded trade, money circulation, and cultural understanding. In order to finance the initiative, China will have to go through great lengths in amassing funds for the megaproject. In addition to other financial institutions that will help finance OBOR, the Chinese government has created two OBOR-dedicated financial institutions: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), with an initial capitalization of $100 billion, and the Silk Road Fund (SRF), with total investment of $40 billion. The establishment of large dedicated public financial institutions like AIIB and SRF will be the main actors in the achievement of OBOR. The additional three existing Chinese financial institutions that will be key in financing OBOR are the China Export-Import Bank, the China Development Bank, and the China Investment Corporation. (Shah, 2016).

OBOR will make financing of the infrastructure along the route possible mainly, by providing alternative sources of funding to traditional public finance.

OBOR will make financing of the infrastructure along the route possible mainly, by providing alternative sources of funding to traditional public finance. The initiative will be driven largely through Public Private Partnerships (PPPs). Where Chinese companies will play a key role. With the OBOR financing model of Chinese loans paying for Chinese contractors. With this model, the investments in the respective countries where the road goes through is de facto building economic ties between China and the host government. OBOR will serve to facilitate greater market access to economies along the trade routes for Chinese companies, secure natural resources for China, expand and strengthen Chinese hegemony, and provide an outlet for China’s investment led growth model to continue. The vast majority of countries along the Silk Road are developing countries that need to improve their general infrastructures. Pressures continue to mount as populations rise, urbanization continues, and ongoing industrialization and economic development requires higher level infrastructure which they can’t afford and lack the expertise to realize. For these reasons China’s investment model of PPP’s will allow these countries to build the necessary infrastructures through the realization of OBOR. The private sector across many of the developing countries along the Silk Road is still relatively new and lacks resources to develop the required high capacity infrastructures. Relying on domestic companies for these states is thought to be very difficult and will surely lack in quality and high capacity requirements.

The OBOR financing model is based on loans from Chinese financial institutions like the AIIB for example to pay for Chinese contractors that will be responsible in building the projects along the way.

The OBOR financing model is based on loans from Chinese financial institutions like the AIIB for example to pay for Chinese contractors that will be responsible in building the projects along the way. These firms are capable in terms of resources and expertise to build high capacity infrastructures, and are a great way for these countries to achieve their goals. However, this will facilitate greater Chinese control of projects, create economic benefit for China and develop the capacity of domestic private sector firms. This Chinese engineered model offers the developing countries alongside OBOR an opportunity they can’t refuse, while securing Chinese influence over an extremely vast area.

To show an idea of what this model will represent in the future, the initiative has already hugely boosted trade and investment between China and countries along the OBOR routes to more than US$1 trillion in 2015. Chinese exports to these countries exceed those to the US and the EU; China’s top two export destinations. This trend will continue as ongoing investment in supporting infrastructure encourages trade flows. (LSE, 2017)

The Shift towards a Beijing consensus?

Under the framework of Xi Jinping’s ‘fen fa you wei’ foreign policy, Beijing’s astonishing economic ambitions are largely supported through the financial institutions put in place. These banks have been thought and installed for national purposes and for international expansion purposes as well, OBOR being a perfect example of it. Internationally, the AIIB, the NBDB, and the other Chinese initiated institutions have comparable goals as the IMF and the World Bank have for the West and especially for the U.S. But the largely differ in economic ideology and decision-making. This different policy choices China utilizes in their economic assistance to developing countries is commonly known as the “Beijing Consensus”. The “Beijing Consensus” is used to distinguish China’s economic development experience from the “Washington Consensus”, the policy toolkit offered to developing countries by US-based and influenced international organizations. An emerging BC has been recently pushed forward by China, with potential to significantly influence the developing countries’ economic development.

The BC, differs greatly form the WC, and represents Chinese economic ideology on how to export its economic influence. In a way, it does not try to export its economic model to developing countries but rather merely offers its help and allows the receiving country to choose its general economic path as it wishes. Whereas, the WC sets policy recommendations to establish a free-market, an outward orientation, and prudent macroeconomic policies. The economic objectives like growth, low inflation, a viable balance of payments, and an equitable income distribution would be results of policy recommendations known as the WC. However, these recommendations in practice work in the form of “coercive conditionality”. The developing country has to confine with the policy recommendations to liberalize their economy, and maintain almost no government control on it. The country receiving help is to accept the Western liberal economic model and change their existing system, and in return, economic assistance will be delivered. This fundamental difference between both notions has pushed some developing countries to turn towards the BC instead of the WC. OBOR is a way for China to convince the world to turn towards the Beijing Consensus. “Welcome aboard China’s train of development. China is willing to offer opportunities and room to Mongolia and other neighbors for common development. You can take a ride on our express train or just make a hitchhike, all are welcome”.- Chinese President Xi Jinping.

There have been major setbacks, and dissatisfaction with the results the WC has brought in some developing countries. Mainly in the 1990s, with a global economic crises arising in the global south. The US-influenced international tried to slightly change the WC and reinventing it into a Post-Washington Consensus more adapted to individual cases and dropping the ‘one size fits all’ policy. Nevertheless, on the one hand the recent financial crises that started in the US, and on the other a Chinese example of exceptional economic growth have had its effects in the developing world. The Chinese experience stands as the ultimate success story among developing countries. China has achieved significant economic development progress by having an average economic growth rate of 10%, leaving the category of a classic developing country to an upper-middle income country. This success story led gave the BC a strong argument as enabling developing countries to fit into the international system by achieving economic success still while preserving their independence.

The AIIB and NDBD, are the main Chinese initiatives to integrate the idea of the BC as a new alternative for the world. As initiator and main contributor in these projects, these institutions will serve Chinese interests in achieving the latter’s foreign policy goals.

The AIIB is a multilateral development bank, and is created as the Asian alternative for the US-based World Bank. It consists of 57 founding members from Asia, Africa, Europe and South America, and is headquartered in Beijing. It has started its operations in 2016. The AIIB has an initial capital of US$ 100 where China has provided about US$ 30 billion, India US$ 8 billion; and Russia US$ 6.5 billion making them the three largest contributors to the AIIB’s initial capital. China will have 26.06% of the total votes and thus the largest voting right. With this voting power, China will be able to block any decision that requires a super majority. But the CCP has recently declared that they will not exercise their veto power, in contrast to the American practices at the IMF and World Bank. The AIIB will focus on financing infrastructure projects mainly in Asian countries and as stated before will be the main financer of OBOR. The AIIB is to become a major influencer of economic development trajectory of Asian countries in the near future, and will inevitably be in competition with the Washington backed international organizations.

The NBDB is a multilateral development bank that will provide funds to its member states during times of crisis and will also finance infrastructure and development projects around the world. It is set to have a capital of US$ 100 billion. China provides US$ 41 billion, India, Russia and Brazil US$18 billion, and South Africa US5$ billion for the authorized capital. It is a Chinese-based institution with its headquarters in Shanghai and the first president is from India. This organization plays a major role in institutionalizing the BRICS cooperation, and potentially rivaling the US-backed IMF and World Bank. It works without veto power and all BRICS countries will have equal votes. The appeal of this organization to developing countries will shape its future influence, and China as the biggest contributor to the funds will inevitably play a key role in operations of the bank. (YAĞCI, 2016)

Main Challenges of OBOR :

Despite China’s great ambitions, The Chinese Communist Party founds itself in challenging domestic problems. Remaining corruption is still an issue even after Xi Jinping’s aggressive anti-corruption policy. The country also faces a widening income gap, an aging population, and a concerning deteriorating environment. Even with enormous growth over the last decades, 200 million Chinese still live in poverty today. China is well aware of these pressing issues in light of its new foreign policy initiatives. It would be a mistake to not take them into consideration when analyzing China’s political and economic expansion. As an aspiring rising power, the way through which they will deal with the numerous domestic challenges will be the determinant factor of the extent at which China’s ambitions will or will not be met.

OBOR is a central Chinese project in the struggle to deal with domestic challenges. Many of the infrastructure projects proposed under OBOR would benefit China’s poor rural inland regions, integrating them in the global economy and helping to rebalance the rapidly growing wealth gap. They are to help China reach a more sustainable development and allow it to move its labor-intensive activities overseas. This move will help solve the severe environmental problem that China faces today. However, China faces many challenges in implementing OBOR.

There are many questions as to the financing of AIIB and OBOR. Both projects demand enormous concentrations of funds. This means China can’t tolerate slowing growth any longer. The AIIB and OBOR are supposed to boost innovation and productivity for China and prevent a slowing growth issue. But it remains to be seen if they will be capable of sustaining the actual slowing economy growth and a falling foreign exchange reserve China faces today. Funding the AIIB and OBOR may present China with a real challenge.

Next to the enormous economic challenges OBOR is representing for China, security will be another major issue. For example, as part of OBOR, China will build 81,000 kilometers of high-speed railway, more than the current world total, involving 65 countries. Who is going provide the necessary security for the building and maintaining of so many projects in so many different countries and regions. The Kashgar-Gwadar economic corridor links western China and Pakistan with roads and pipelines and will send electricity to Pakistan. The route passes through some of the world’s most vulnerable and conflict-ridden territory. The land route also means to pass through Myanmar, in areas where security would be impossible to guarantee right now. These issues raise questions about how China plans to deal with the security threats alongside OBOR.

As a third challenge, many recipient countries in Asia have poor credit, which means many projects may be promising at the beginning but will be difficult to pursue when more investments will be needed. Partnership agreements in most of these states are reached at the top levels of government. However the implementation of projects are dealt with at the local or regional level only. Local governments often collide with the will and interests of the central government’s policies and do not always cooperate with foreign investors. The public-private partnerships that are to be made with the states therefore are not sufficient to put it into reality. This means that depending on the geographical positions of the infrastructure projects the waiting time and processes will vary greatly in time. And some projects might take many years to see light. (Zhu, 2015)

The South East Asian Challenge:

Next to the evident economic challenges OBOR represents for China, a number a geopolitical factors puts China in a complicated situation that might harm the materialization on the megaproject. One of the current issues it is facing is in relation to the South China Sea conflict. With regard to the South China Sea dispute, Xi Jinping has been much more assertive in China’s territorial claims over the disputed waters. Since late 2013, China began transforming seven small islands under Chinese sovereignty in the Spratly Islands into massive artificially built islands. This move backlashed into strong accusations that Beijing was “militarizing” the South China Sea dispute. And in January 2013, China refused to participate in an international law case legal case brought against it by the Philippines under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which challenged Beijing’s maritime jurisdictional claims in the South China Sea, and rejected the final verdict when it was announced three years later. In May 2014, China deployed the HYSY-981 drilling platform into Vietnam’s claimed exclusive economic zone (EEZ). This provocative move triggered a major crisis in the respective countries’ relations.

At the same time, Xi has also showed clear signals of goodwill and cooperation towards the countries of Southeast Asia. One of the main signs of this goodwill lies in the OBOR initiative. Especially for the Maritime route, which is meant to pass through the disputed territorial waters of the South China Sea. This project seeks to help South East Asian nations develop needed infrastructures to enhance trade in the whole region. So are Xi’s assertive policies in the South China Sea and OBOR contradictory? It is delicate for China to promote cooperation via OBOR while simultaneously engaging in assertiveness towards the South China Sea. The dispute, over the past decade, has led to rising tensions between Beijing and the Southeast Asian claimants (Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei and even Indonesia). But also between China and other stakeholders like the United States and Japan. The Asia pivot policy, carried out by the previous US administration has intensified the tensions in the South China Sea. China faces the threat of a diplomatic rapprochement or even an alliance from the South East Asian countries with the US at some point. (Nie, 2016) With that in mind, China is still the biggest trading partner of ASEAN. And both entities seek to foster their trade relations and increase their volume to 1 trillion USD by 2020. Something that would be made possible through OBOR. China’s moves may eventually demand a unilateral response from the ASEAN intergovernmental organization. But for now, it seems that economic interest exceeds political positions. Still, The South China Sea conflict may pose a significant challenge to the development of maritime Silk Road of China’s OBOR. (Lim, 2015)

India’s Position:

India finds itself in a complicated situation, regarding the OBOR initiative. It is geographically situated within its maritime route, and the cooperative views shared amongst most of its neighbors towards the project, signifies a loss of influence from India on its geographic influential zone of South Asia.

India’s views on the Chinese initiative “One Belt One Road”, has been a subject of intense debate in the country. For Beijing, New Delhi’s response is extremely important and could change the core of the project in South Asia. Whether India joins it or not, the decision is going to have a lasting impact on Sino-Indian relations but more importantly on overall power relations landscape of the whole region. India itself will be significantly impacted by the project weather or not it joins it.

The official response by the Indian government to the OBOR initiative has been very vague for now. China on the other hand raised the issue at the highest level of discussion with its Indian counterparts.

Chinese President Xi Jinping raised OBOR with Prime Minister Narendra Modi, when they met for the first time on the discussion about the BRICS summit in Brazil, in 2014, where he proposed that India joins the initiative. But India did not give its official response yet.

The mere official words India has provided the international world was when Foreign Secretary S.Jaishanker during a conference in Singapore said: “it is not incumbent on other countries to necessarily buy into such unilateral initiatives.” From this remark, it can be presumed that India sees OBOR initiative as a National Chinese initiative. From what can be understood, given the ambiguity of such an Asian Marshall Plan, India has chosen the path to wait and watch in order to buy some time for crafting its own role and position in such initiative (Krishna, 2016)Though, India has recently released a statement urging China to engage in a meaningful dialogue with India, specifically on the China-Pakistan economic zone problematic. (Ministry of External Affairs of India, 2017)

In any case, India’s main direct problematic of OBOR is obvious. The China-Pakistan economic zone (CPEC) has maritime and land implications for India, and more specifically it violates Indian territorial claims on disputed territories in Kashmir. Finalized in April 2015, with of 51 agreements, the CPEC consists of a number of highway, railway and energy projects, all connected to the newly developed port of Gwadar on the Arabian Sea. The entirety of the project is estimated to be valued at $46 billion. And together it is meant to be generating 700,000 future jobs in Pakistan. India’s opposition to CPEC is very clear. CPEC passes through Pakistani-Occupied Kashmir, which is a contested region between India and Pakistan. Agreeing to this project would mean that India indirectly denounces its claim over Pakistani-Occupied Kashmir, which is not India’s actual policy towards it. (AHMAD, 2016)

In addition, CPEC is not merely an economic corridor, but also has strategic significance. The total investment in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor is disproportionate to the projected Chinese profit of this project. This corridor would allow China to have access to the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean, which is a great strategic position.

China is open to discuss the possibility of including India within the CPEC project with consultation of Pakistan. But as for now, India is extremely unlikely to accept the invitation. The Indo-Pakistani quarrel seems to be very tense today, with Pakistan denying India trade route to Afghanistan, which damages the whole Northern India economy. But on the other hand, with India’s accession to the project, the whole could reap a lot of benefits. India will not only get a direct land route to Afghanistan and Central Asia. But it will also be given an opportunity to de-escalate the tensions between India and Pakistan based on economic cooperation. However, today this scenario seems very unlikely.

In addition to its worries over the Indian Ocean, India perceives the growing Chinese influence in the Indian subcontinent. The increasing Chinese aid and investment in its neighborhood, and the development of OBOR, forces India to take counter-initiative to balance China’s assertiveness. These Chinese initiatives do challenge Indian supremacy in South Asia.

To counter this trend, India has initiated its own infrastructure connectivity projects for trade and commerce in the region. India signed a cooperation agreement with Iran to connect and develop Chabahar port with Afghanistan, through a series of Highways. This Highway gives India passage to the Central Asia up to Kazakhstan, and thus getting around the Pakistani problem.

Next to this initiative, India has put forward 2 major Asian projects with important implications. The first one is called Project ‘Mausam’. It is a unique project, launched in 2014 at the 38th World Heritage Session at Doha, Qatar. The main purpose of this project is to re-explore the cultural routes and maritime landscapes countries around the Indian Ocean. And in the process re-connect India with these coastal countries and establish a mutual understanding like in the past. The second project is called The Spice Route Project. India launched Spice Route project in order to connect it to 31 countries lying along the ancient Spice Route. The route starts in India’s state of Kerala, the major producer of world famous Indian spices. Kerala has maritime trade access to more than thirty countries and India wants to reorient the relationship with all these nations through trade, tourism, and cultural exchange.

China has expressed its desire to connect its One Belt One Road initiative with India’s spice route project and Project Mausam. But the future of Sino-Indian rivalry over strategic assets in Asia is likely to intensify in the near future, and OBOR will still be central for the development of this rivalry. (Krishna, 2016)

The US Position:

The US response to the Chinese proposal is ambivalent for now. Though, almost all American assessments on the issue begin their discussion of Beijing’s goals by claiming that China seeks to use OBOR to export its surplus capacity in construction materials, engineering services, and perhaps even labor. (Chance, 2016)

Although the U.S. has expressed its wishes to take part in OBOR, concerns are frequently raised by American officials and scholars about the fact that China seeks to create new international institutions or economic frameworks that work as parallel alternatives to US-led organizations. Mainly the Bretton Woods institutions (WTO and IMF), which have been the main regimes leading the global economy since the end of World War Two. To some, OBOR and AIIB represent the main entities that challenge the American foundations of the economic order. And they introduce the beginnings of a “Sino-Centric” economic world order.

In addition, China’s activities in other policy areas, such as in the South China Sea, shape interpretations of OBOR’s place in Chinese strategy. Assertiveness, or aggressiveness in the security domain results in economic policy being viewed as assertive or aggressive as well. (Chance, 2016)

Recently, the Trump administration has expressed its concerns on the Belt and Road initiative. From U.S. secretary of state Tillerson recent speech ahead of his trip to New Delhi, his comments about China and OBOR led to believe the US is working on a counter-strategy, to balance the rise in influence of China. In addition, U.S. Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis’ recently noted that “In a globalized world, there are many belts and many roads, and no one nation should put itself into a position of dictating ‘one belt, one road’.”

This new narrative implies an alignment with Indian interests. It’s unclear how specifically the United States if and how the United States will go about to contain the Belt and Road initiative. But it seems increasingly likely that Washington will align its position to other like-minded Asian states including India. But also Japan, and possibly Australia. (Panda, 2017)

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the effort in this paper has been to portray the implications of China’s the One Belt One Road infrastructure megaproject. The relatively new foreign policy goals of the People’s Republic of China, are literally “striving for achievement” (fen fa you wei). OBOR is the incarnation of this new paradign China seeks to create. This truly gigantic and ambitious project will mean immense changes for many regions in Asia and beyond. Further, it has the potential of reshaping the region’s economic situation as a whole, and change the Asian balance of power towards China. And to an even further extent, reshape the leadership and the landscape of the international economy towards a more Sino-Centric position. The new concept of this Beijing consensus shows many signs of success, especially as a consequence of its attractiveness in the developing world. This new trend will most certainly demand adaptations in the Washington consensus if it is meant to maintain its leadership, and not be replaced by a Chinese economic hegemony.

Liam Weberman