Renata Segura is an expert of Latin America. She currently works for the IPI Global Observatory.

Since the peace process between the government of Colombia and the guerrilla group Fuerzas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) began in October 2012, perhaps the greatest question has been if the negotiations will yield an agreement that both facilitates peace and also responds to the claims for justice. The justice architecture that was made public on September 23, 2015 addresses both, and while pending questions on how exactly will it operate remain, the newSistema Integral de Verdad, Justicia, Reparación y No Repetición(Cohesive System of Truth, Justice, Reparation and No Repetition) unveiled in Havana is an innovative take on transitional and restorative justice. By announcing this new agreement, together with a final date for the negotiations (March 2016), and that the FARC would demobilize and disarm 60 days after the signing, a peace process that at times seemed moribund has regained strength, with most (but certainly not all) Colombians celebrating the possibility of a near-end to the 60-year civil war.

A very important feature of this new system is that it aims to address all crimes committed during the conflict, and not only those of the FARC. This has been a salient feature of the process, which has infuriated its opponents. The FARC has consistently argued that their actions need to be reviewed within the context of a conflict that saw excesses from the state and the paramilitary. In fact, early in the negotiations, the FARC declared themselves a victim of the war. It is notable, then, that the FARC has decided to admit their responsibility. The system announced last week creates two main institutions to address these issues while seeking to have some balance between peace and justice:

- A Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de la Verdad, la Convivencia y la No Repetición (Commission for Truth, Coexistence, and No Repetition) will be created, and will focus on reparations for victims. With 7.6 million registered victims, achieving fair reparations will demand important resources. It hasn’t been established what assets will be used for that purpose.

- A Jurisdicción Especial de Paz (Special Jurisdiction for Peace), formed by Salas de Justicia (Justice Halls) and a Tribunal para la Paz (Peace Tribunal), will be staffed by a majority of Colombian Justices, and also some foreign ones. Besides contributing to the goal of finding truth and help with reparations, this will be the central tool to impart sanctions to those responsible for the gravest crimes committed during the conflict. The statement emphasizes they will focus on the most serious and representative crimes.

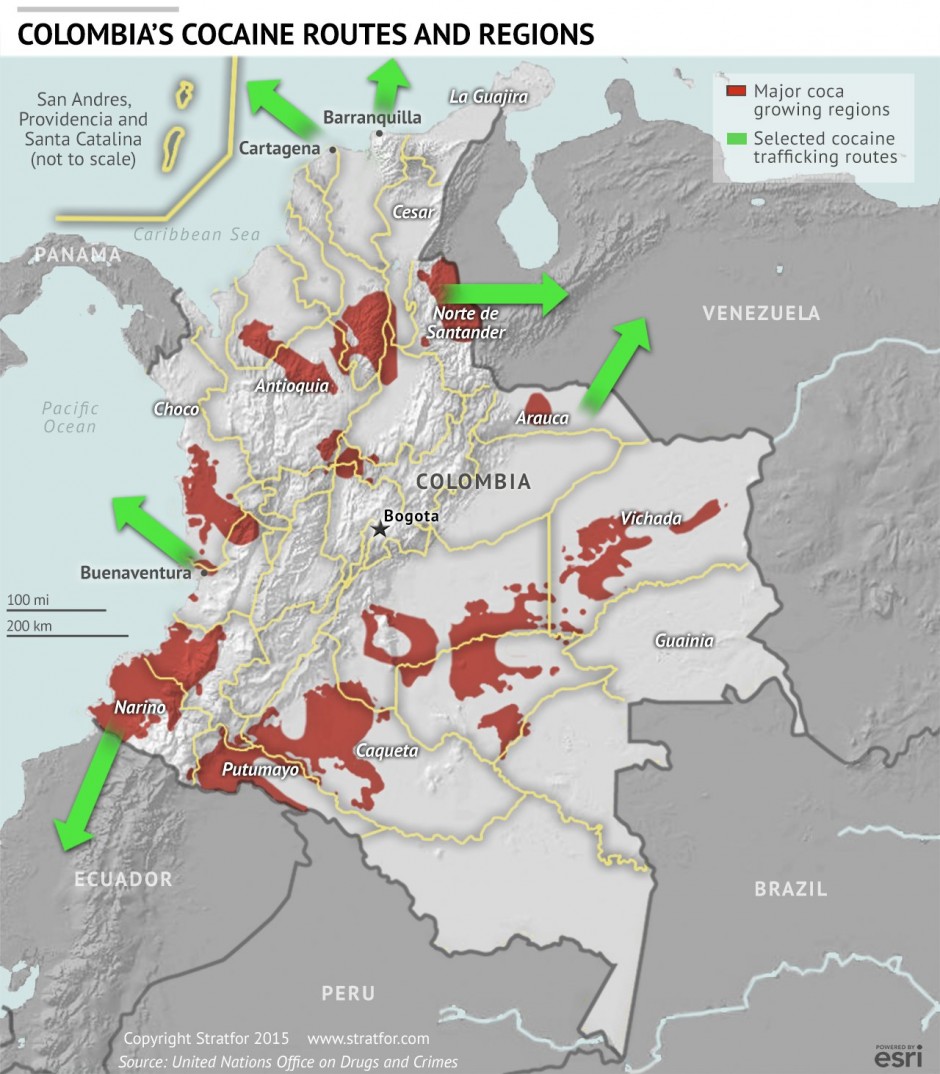

From the beginning of the process, a central tension was evident: as the FARC came to the table as a negotiating party and not a defeated army, they openly refused to “spend one day in jail.” At the same time, the Rome Statue and other international legislation that hadn’t been in place in previous peace negotiations with other armed groups in Colombia imposed new justice standards. Additionally, the question of how an already overwhelmed justice system could handle trying every single guerilla member remained.The agreement announced a law granting “the widest possible amnesty” for political crimes and the crimes associated with them. To satisfy the requirements of Humanitarian International Law, this amnesty law will exclude crimes against humanity, genocide, war crimes, including taking of hostages, torture, forced displacement, extrajudicial executions and sexual violence. These crimes will be investigated and judged by the Special Jurisdiction.The Special Jurisdiction has laid out two different processes. Those who are willing to acknowledge their responsibilities in the conflict will get sentences between five and eight years—sentencing guidelines that mirror those of the demobilization process of right wing paramilitaries in 2005. The announcement, however, refers to these sentences as “restrictions of freedoms and rights,” which means that these guerrillas won’t serve regular jail sentences, as they had stated from the beginning. It is important to note that the system will also apply to members of the Colombian Armed Forces or right wing groups. In particular, there has been a preoccupation that the almost 3,500 extrajudicial executions known as the “falsos positivos” were not left in impunity. Those unwilling to acknowledge their responsibilities, or do so late, will receive sentences of up to 20 years.To be sure, there are numerous open questions, and as always, the devil will be in the details. Who gets elected to the Tribunal and the Justice Halls, and how this endeavor will be financed are the first and most obvious ones, but far from the only ones. The agreement, for example, includes a component of restorative justice which states that the sentencing will guarantee the fulfillment of duties and work that satisfy victims’ rights. This vague description will no doubt invite complicated debates. Another important pending question is if drug trafficking can be conceived as a political crime (or an associated crime) and thus eligible for amnesty. A clue in this regard can be found in the recent statement of the President of the Supreme Court José Leonidas Bustos, who said it could be understood in this way if it was used “as a tool to financially support the political ends of the armed struggle.” Given the widespread involvement of both FARC and right-wing paramilitary in the traffic of illicit drugs, this decision will be hugely important—and no doubt the United States will keep a close eye on this issue.The road ahead is by no means clear, especially as the parties have decided that “nothing is agreed until everything is agreed,” and there is strong opposition to the process led by ex-president and now Senator Álvaro Uribe. The sticking point at the negotiating table on how the demobilization and disarmament will take place will be no doubt extremely difficult. The government has promised that this peace agreement will be endorsed by the Colombian public, but it’s not clear yet if there will be a referendum or a different tool will be used. In the meantime, Congress is already studying a constitutional reform that would allow for the implementation of the agreements, and the Attorney General announced a halt on the imputations of charges to all members of the FARC. For Colombia to succeed in the enormous task ahead, it will need broad support from the international community. But more importantly, it will need support from Colombians themselves in the form of a radical step: to search for forgiveness and reconciliation. Ending the longest and one of the most violent conflicts in the continent surely is worth all of these efforts.