Politics can be a rough business. What happens when leaders lose their positions of authority, the halls of power close, and their supposed friends and allies desert them? What happens when a leader’s very survival is in jeopardy? Political defeat can come from the ballot box or the bullet, and there’s a big difference between leaders who find themselves shut out of their political system but who can remain in their countries and those who, through the loss of power to rivals or a popular uprising, end up banished from their homelands. Leaders in many parts of the world are not always afforded the luxury of safety when the political tides turn against them.

So when a leader — whether a democratically elected figure or a brutal strongman — falls in a country where the political system is defined more by personal status than institutions, the stakes are high, even life-threatening. In certain circumstances, the threat of being sent to the International Criminal Court can motivate embattled leaders, such as Syrian President Bashar al Assad, to dig in and fight. In other cases, the vanquished must flee for safety abroad out of fear of retribution, prison or death at home. When the decision to flee is made, some countries may step forward to take them, but the decision to do so does not always come out of altruism. And more often than not, the final destination of a defeated leader can be geopolitically illuminating, for the locations of their extended exile generally depend on the foreign policy interests and domestic concerns of the host state. A long-standing relationship between a potential host and the now-banished leader can also play a role.

When a leader feels as if his or her back is against the wall — what Sun Tzu called being on “death ground” — the chances of bloodshed escalate dramatically. When Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos faced massive protests in 1986, he considered staying and fighting, which would have inevitably sparked widespread violence. At that point, Washington decided that despite his kleptocratic rule, Marcos, who had been a stalwart Cold War ally, had earned an extended stay in the United States. Marcos and nearly 100 members of his family (as well as heaps of plundered Philippine goods) piled into two U.S. Air Force aircraft bound for Hawaii. The incident revealed just how far America would go for a fallen ally — and to prevent chaos and violence.

Relying on a Patron

If a leader must choose where he or she must flee, their first choice is usually a patron state, oftentimes the former colonial power. Client-patron state relations are commonly a determining factor because of the close political, economic and cultural dynamics between the two countries. Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovich’s flight to Russia in 2014 is one such example. A political golden parachute may even be part of the deal between a patron state and its client state leader, just as regime security can be.France is a master of this tactic, having negotiated dozens of secret defense agreements with its former colonies during the Cold War, guaranteeing the client states’ national security in exchange for economic and political concessions. Successive French governments have frequently opened their arms to downtrodden leaders, including some from France’s former colonies in Africa, who can benefit from living in Paris near their countries’ diasporas and slowly rebuild their political fortunes. In certain situations, however, leaders fall as a result of a patron state’s meddling, as many French-speaking African leaders discovered when they tried to reduce France’s influence in their countries. When this happens, ousted leaders can end up in the state that backed them in their battle against the patron state or in an entirely neutral country, as Madagascar’s deposed president, Marc Ravalomanana, did. When Ravalomanana, who was seen as much closer to the United States than to former colonial power France, was chased from office in 2009, he took refuge in Swaziland and South Africa instead of France, as did his predecessors.

A Tempting Intelligence Source

In the early 1500s, Florentine statesman Niccolo Machiavelli warned the princes of his day to be wary of exiles because their advice could lead to “shame or very grave injury.” But the prospect of gaining intelligence from an expert from the highest level of a given country, capable of providing the best intelligence regarding country-to-country relations or the decision-making process of opaque administrations, has proved tempting — and rewarding in some cases. That an exiled leader’s stay is predicated on the continued goodwill of the host country means that it is less likely the exile will turn down calls for an intelligence debriefing. Moreover, the ability of a host country to keep tabs on a former leader in its midst, and even provide a generous stipend, increases the dependency of the latter on the former, a dependency the host could cash in on later.

After falling out with Libyan dictator Moammar Gadhafi, Gen. Khalifa Hifter realigned with the CIA in an attempt to unseat his former master. When his group failed in that effort, Hifter and 350 of his men were airlifted to Zaire before eventually ending up in the United States. The general was made a U.S. citizen and lived in Virginia for nearly two decades. There is little doubt that providing intelligence about the Libyan government to U.S. officials was part of the deal. His return to Libya in 2011 to command forces in the Libyan civil war means that although his fortunes have changed dramatically, there is almost certainly some form of an ongoing relationship between him and the United States as he attempts to exert his influence.

On the downside, inaccurate intelligence gained from an exiled political figure can warp the host country’s interpretation of events in another country. Machiavelli’s warning that exiles are biased in their own ways and often want to return to their homeland above all else still rings true. Before the United States invaded Iraq in 2003, Ahmed Chalabi, an Iraqi exile who founded the Iraqi National Congress and was considered a leading Iraqi political dissident, promised eager U.S. policymakers that Iraq — in which he had not stepped foot for decades — was ripe for democracy. American planners were convinced of his influence in Iraq and partly relied on his claims in their preparations. But when the troops went in, the United States discovered a reality very different from what Chalabi had sold them.

Influence From a Distance

Naturally, exiled leaders can wield power from abroad. Sometimes the distance even magnifies their clout as the leaders remain untainted by the vicissitudes of domestic politics. For example, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini lived in self-imposed exile starting in 1964, first in Turkey, then in Iraq and France, but bootleg recordings of his speeches were widely popular on the streets of Iran. This seemingly invisible influence paved the way for his triumphant return to Iran, where an estimated 6 million people greeted him. Another leader who pulled the strings from exile was ousted Thai Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, who orchestrated the installation of not one but two close family members as successors.

The biggest benefit of providing a haven for a leader under fire is devising a political solution to an existing conflict, such as a civil war. Another potential upside — although much less likely — is a political comeback. When a country takes in a leader on the run, it might be placing a bet on the future.

Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif is a rare example of a successful return from exile. After he was deposed by the military in 1999 and thrown into prison to serve a life sentence, the Pakistani government unexpectedly released him. Several hours later, he landed in Jeddah aboard a jet owned by the Saudi royal family to begin eight years of exile in Saudi Arabia. After political forces sufficiently changed, Sharif returned to Pakistan in 2008, built an opposition coalition and won an unprecedented third term as prime minister in 2013. Around that time, Pakistani-Saudi diplomatic and military ties warmed. But Saudi Arabia seemingly overestimated what it thought it was owed by the leader of the Muslim world’s only nuclear power and second-most populous country. Riyadh wanted Pakistan to forgo its long-held neutrality in the Muslim world by sending troops to help the kingdom in the Yemeni civil war and by turning away from Iran. Pakistan refused on both counts, demonstrating that personal relations rarely trump national interests.

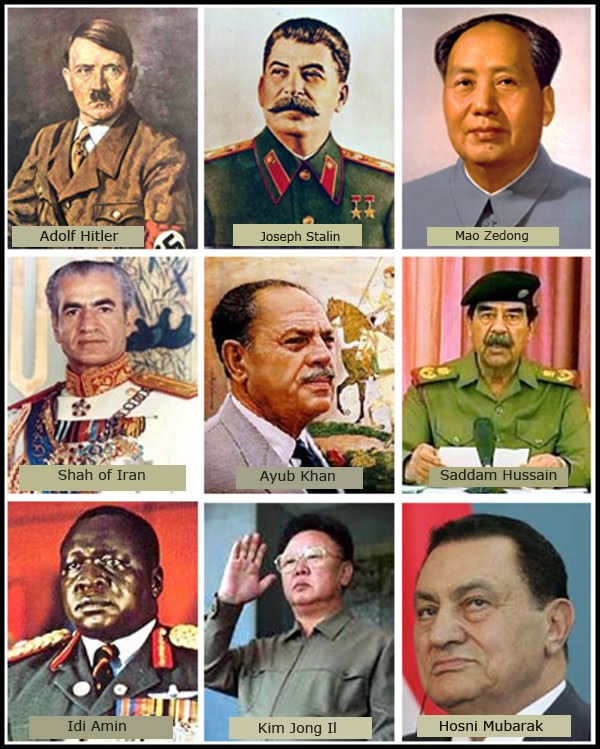

The Politically Untouchable

A drawback to accepting a controversial exiled leader is the potential blowback a host country can face. Certain fallen leaders are perceived to be untouchable by a patron state — no matter the strength of past relations. A notable example is Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the deposed shah of Iran who was forced into exile in 1979. The controversy surrounding his reign prompted the administration of U.S. President Jimmy Carter to deny him an extended stay (apart from temporary medical trips), forcing the ailing monarch to travel from country to country — including stays in Morocco, the Bahamas, Mexico and Panama — until Egyptian President Anwar Sadat finally granted him a reprieve in 1980, not long before Pahlavi’s death. In a similar case, Mobutu Sese Seko, the former leader of Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) who plundered billions of dollars from his country before being forced out in 1997, first fled to Togo, where he was coldly received by the government, before ending up in Morocco, where he died. Saudi Arabia has given refuge to exiled leaders unwelcome in their former patron states, helping to sweep situations under the rug while gaining favors from the powerful patron nations. When Ugandan dictator Idi Amin sought exile abroad, the kingdom stepped forward, offering the fallen strongman a gilded refuge in exchange for staying out of politics.

While not a political exile in the traditional sense, former NSA contractor Edward Snowden, whose leak of intelligence data led to espionage charges in the United States, fled his homeland to seek refuge abroad. Snowden eventually found sanctuary in Russia after having applied for asylum in 21 countries, only to see most of his requests denied (more often than not as a result of U.S. pressure). Snowden’s exile put additional strain on U.S.-Russia relations at a time when the situation in Ukraine was deteriorating.Hosting Snowden was a windfall for Moscow, however, which was able to demonstrate its willingness to stand up to the United States. In addition, Russia’s intelligence service was afforded an opportunity to debrief Snowden for any further intelligence secrets.

Exile is a fact of life in the rough-and-tumble world of many countries’ political systems. So when we examine exile at the geopolitical level, a leader’s fall can reveal the true nature of previously hidden relations among nations.