When I was a teenager, I had to drive my older brother to downtown Phoenix. He couldn’t drive himself; he’d made a series of poor life choices, so it fell to me, the relatively responsible one, to ferry him about. The Global History of the Alt-Right

As we drove, he ranted to me about blacks, Mexicans, and Jews, using all the tried and true tropes of the traditional white supremacist right – tossing in, for my “education,” that the Bible had given blacks over to whites as slave-animals. When we pulled up to our destination, a Mexican guy was hanging out on the Phoenix equivalent of a stoop; my brother would have to pass by the guy. I asked him, in that teenaged point blank manner, what he thought of the man.

“Oh no,” my brother replied. “He’s one of the good ones.” Switching off from racist extraordinaire, he proceeded to carry out his errand and have a light, polite chat with the very man who’s race he’d spent much of our journey together trashing.

It was my first encounter with the double-think that would swirl to become the Alt-Right.

The Alt-Right defined

The Alt-Right is a brand-new lexicon that came of age during the final months of the U.S. presidential campaign in 2016. The term itself is traceable to 2008. As written in Salon:

In 2008, conservative political philosopher Paul Gottfried was the first to use the term “alternative right,” describing it as a dissident far-right ideology that rejected mainstream conservatism.

Yet the intellectual force, not to mention the personalities, of the Alt-Right are considerably older: it pulls threads from old school fascism, 19th-century nativism, slavery-produced white supremacy, Goldwater conservatism, and 1970s-style disillusionment. It is also not a uniquely American phenomenon: Alt-Right forces have bubbled and gurgled throughout the rest of the world since the 1970s.

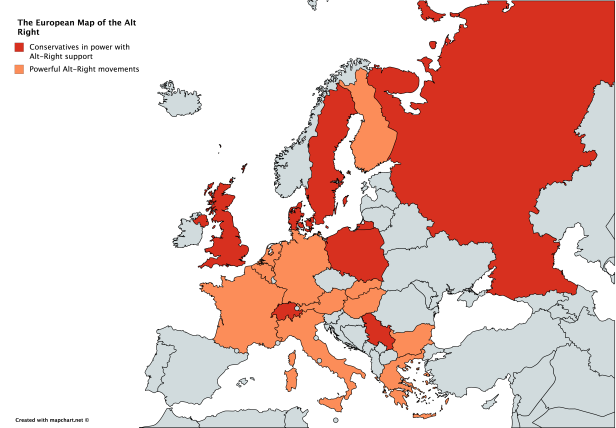

Today, versions of the Alt-Right are global. Virtually every developed country has at least one Alt-Right political party: even idyllic New Zealand has New Zealand First, an anti-immigration party. The English Alt-Right, head by the UK Independence Party, helped force Britain out of the European Union, and has since pushed its Conservative Party further right.

The populist Finn’s Party in Finland has surged to heights it’s never enjoyed before; the Alt-Right-leaning Sweden Democrats Sweden Democrats are fighting against more refugees. Critically, in the Netherlands, France, and Germany, Alt-Right parties are growing to become not fringe but mainstream political phenomena. As the Dutch prepare to vote on March 15th, Geert Wilders, once a political pariah for his extreme Rightist views, is leading in the polls. Marine Le Pen, another Alt-Right force, has spent decades hoping to reach the political popularity she now enjoys.

How did we get here? And what does it say about the international system that produced this force?

The Alt-Right: “Westerners” only

The basic Left-Right divide begins in the French Revolution, when Right-wing forces supported the monarchy and Left-wing forces wanted to introduce Enlightened government through a republic. Depending on how hard they believed, their views could be quite violent.

Since then, Leftist forces have sought change: Rightist forces sought to slow or even reverse it. The Alt-Right builds on the conservatism and Rightist impulses of Europe and the United States. We should step back and look at those modern roots.

Western conservatives used to represent industrial, imperial/royal, and nationalist interests. They built the great empires of the late 19th century; their Christian zeal sent missionaries worldwide as their gunboats shelled native peoples into submission. They also managed to squabble their way into World War I, which completely discredited their royal factions and weakened their imperial ones.

But they kept hold of their industrial and nationalist ideologies until World War II exhausted those as well. Inspired by Allied propaganda, conservatism retooled itself as the ultimate arbiter of freedom, mostly via economic choice. On the western side of the Iron Curtain, it came to represent zealous anti-Communism (especially offended by Soviet godlessness), anti-statism (conflating Keynesian economics with Soviet central planning, which was a nicely dishonest way to start a movement), and cultural nationalism. That last part was a fine needle to thread: cultural nationalism could be contrasted with the Soviet boogeyman, which was trying to refashion the many subjects of the Soviet empire into a single cultural entity. But it could go too far: millions had lived through Axis cultural atrocities.

They did not want to be seen allied to the old fascist survivors of the war, who lurked beneath the political surface. Fear of division in the face of the Soviet menace kept the public from gambling on anything but safe bets: the atomic bombing of Japan was too recent, and the many duck-and-cover drills of the 1950s and 60s hammered in the reality of nuclear annihilation.

How the National Front made the Alt-Right template

In 1972, just shy of the 30 year anniversary of the liberation of Paris from the Nazis, Jean-Marie LePen founded the progenitor of the modern Alt-Right: the National Party. Planks of tough law-and-order, cultural and economic protectionism, and anti-immigration held together a coalition of French voters angered by the changes they were seeing in their country. Many of these changes were self-inflicted: France’s stubborn war in Algeria brought the first big wave of African migrants to the continent, producing a subnationality mainstream France could not figure out how to assimilate. Conflicts between die-hard colonialists and the rest of French society led to a wave of bombings in the 60s and the collapse of the Fourth Republic; old school Vichy Fascists found more mainstream allies willing to overlook their past faults in the pursuit of French national glory in Africa.

The National Front became the archetype of the Alt-Right political party: claiming to protect “Western” civilization from both its own decadence (often by alluding that Jews were corroding it from within) and from evil outside forces (like Islam and Communism), the National Front built a shaky base of French voters initially too spread out to have any national effect.

The 1970s coincided with a marked shift in conservatives throughout the West. Most went hard for the neoliberalism of Ronald Reagan and Margret Thatcher, who produced the conservative ideology only recently upended by the Alt-Right. But some split off: rather than seeing tax cuts and free trade as opportunities to get rich, they saw them as opening doors to new, increasingly different foreigners.

It’s important to note they did not reconstitute with out-and-out old school fascists or racists, who also tried, and failed, to reinvent themselves in this period. Skinhead culture was appropriated by fascists hoping for a more modern edge; it fell flat when they refused to stop Seig Heiling. The Ku Klux Klan appointed a supposedly nicer, better-looking leader, David Duke, to wow cameras, but his traditionally vile worldview could not be hidden under any sugarcoating.

Even Jean-Marie LePen couldn’t hold his tongue when it came to the Jews: as recently as last month, he was still making jokes about Jews in ovens.

As Reagan and Thatcher dominated conservatism, the budding Alt-Right could move nowhere. Too easily lumped in with neo-Nazis and fascists, and with too much at stake in the Cold War, the National Front and those like it went nowhere.

The ground shifts: Sunni supremacism, neoliberal corruption, revitalized Russia, and generational change.

Around 2000, the geopolitical understanding of the post-Cold War world began to shudder and break apart. Sunni supremacism began to violently lash out at Western powers long used to dominating the Middle East’s resources and states; Russia started a slow rise out of its post-Soviet collapse; neoliberalism as an economic ideology began to rust, and the generation that fought World War II began to die in large numbers.

All four combined to create an environment perfect for the Alt-Right.

Sunni supremacism provoked more and more Western thinkers and voters to conflate Islam with violence. Despite the best efforts of leaders like George W. Bush, Tony Blair, and Barack Obama, all of whom differentiated between violent supremacists and everyday practitioners, repeated attacks undermined their arguments. This was exactly what groups like al-Qaeda wanted; the more Westerners hated Muslims, the more Muslims would join al-Qaeda. It also thrilled the nascent figures of the Alt-Right. As early as 2005, Geert Wilders was quoted as saying, “The analysis is clear, we have a great problem with Islam, in the Netherlands too.” Once in the political wilderness, Sunni supremacist attacks in the Netherlands suddenly made Wilders appear sensible.

The return of Russia brought a structural discipline to a movement that hadn’t had any before. While Putin himself does not practice an Alt-Right worldview (it’s more like an imperial nationalism, an older school of geopolitical thought), he saw use in the Alt-Right parties budding throughout Europe and America. Since repeated Sunni supremacist attacks made it increasingly okay to slam Islam, the Alt-Right could no longer be hammered as neo-Nazis as readily anymore. (A common Alt-Right defense for why their Muslim-bashing is not the same as Nazi Jew bashing: The Jews weren’t going around beheading people).

Since Putin’s goals were to roll back values-based institutions like NATO and the EU that might threaten his rule (and possibly undo the Russian Federation), he had to find useful assets that could corrode those institutions. NATO and EU values are rooted in neoliberalism: free trade and open borders through the EU and human rights protected by hard power through NATO. By supporting parties that undercut these values, Putin sought to undermine both the NATO and the EU.

We now know about Putin’s Facebook and Twitter bot army andRussian financing of Alt-Right parties throughout Europe. The accusations that the Kremlin did something similar in the United States is gaining credibility. Russian spy tradecraft provided discipline to movements that were otherwise too prone to fracturing.

But that would have been irrelevant had neoliberalism’s cracks not begun to show. Even as early as 2000, it was obvious that free trade deals were widening the wealth gap and benefiting only the upper classes. The battle of Seattle, the anti-globalization protests that took place in 1999, were just a harbinger of the energy that would be mobilized against neoliberalism.

The world realized the emperor had no clothes, however, in the wake of the Financial Crisis, when all the inequalities of neoliberalism were laid bare. Years went by with both American and EU leaders trying to cobble together formulas to save the system without addressing any of the problems caused by it: during that time, conservatives began to drift away from economic freedom and free trade and towards the protectionism that had long been espoused by the Alt-Right.

Finally, and perhaps most crucially, the 2000s also saw the end of the World War II generation as a major political force. The veterans and their memories of Axis horrors died off and left their children and grandchildren without any check on Rightist impulses. Political decency, a key post-war value meant to act as a breakwater again violent, thuggish politics, fell away: politicians and public figures could get away with saying increasingly outrageous things. Rightists felt no responsibility or connection with the Hitler era, and were so less stung by the accusation by their enemies that they were behaving like Nazis.

After all, can you imagine a World War II veteran excusing Trump’s Pussygate?

The perfect geopolitical storm

When one sees Hillary Clinton as the standard bearer of discredited neoliberalism, her defeat makes a lot more sense. So too does Brexit; the European Union was always designed as a neoliberal project. The disappearance of the World War II generation’s political power has coincided with the rise of the Alt-Right’s thuggishness: their check on the Alt-Right was crucial.

Yet these alone might not have been enough to propel the Alt-Right to its heights were it not for the machinations of outsiders. Russian plots to bolster Alt-Right parties have largely worked; their ultimate success will depend on the outcome of both the French and Dutch elections this spring. Moreover, Sunni supremacists welcome the takeover of the West by Alt-Right holy warriors, who want the same civilizational showdown they do. If the Alt-Right becomes the dominant ideology of the West, it would almost certainly mean wider war in the Muslim world.

Now what?

The Dutch election will be critical; should Wilders gain power, it will be another out and out Alt-Right government. That will put both France and Germany in the ideology’s crosshairs. Nobody expected Donald Trump to win the presidency, just as nobody expects Marie LePen, the less overtly anti-Semitic leader of the National Front, to do so in April.

Such electoral victories might tip Great Britain’s conservative movement firmly into the Alt-Right; it already dangerously tiptoes that line. Other borderline governments like Poland, Sweden, and Denmark could also firmly act more like the Alt-Right. That would leave only Germany as a force powerful enough to withstand the complete collapse of neoliberalism. Such a task would be beyond its reach, however, should the United States slip firmly into a new Alt-Right consensus: Berlin cannot hope to stand up against both Russian and American political interference.

In the long run, should the West become dominated by the Alt-Right’s nativism, nationalism, and protectionism, the world risks returning not to the 1930s but to the 1910s, when brute geopolitical interest propelled each power to seek its own short-term gain. The Alt-Right cannot hold together NATO; Alt-Right forces already mumble against it. It actively seeks to destroy the EU. Without either, Europe returns to its pre-war self: an anarchic continent of powerful nation-states unsure of the intentions of their neighbors. That is an environment Russia can thrive in, but it will leave Germany, France, and Britain all the poorer, as they waste resources trying to gain domination over one another.

There are good reasons to believe this won’t happen. Already forces are arrayed against the Alt-Right, most powerfully in the United States. Should Trump be impeached and convicted over his ties to Russia, it could kill the movement globally. This could simply be the final, most dramatic act in the Strauss-Howe Crisis, giving way to a gentler 2020s.

Or it could be the beginning of a new normal. Watch the Dutch today; watch the French in April. And watch how long Trump occupies the White House.

(Correction: The ruling government of Sweden is not an Alt-Right leaning government; the Alt-Rightists there are the Sweden Democrats. Sorry.)