A lack of coordination among Germany’s officials is chipping away at the popular perception of the Berlin government as a well-oiled machine. In the latest example of internal discord, a government spokesperson said Thursday that Interior Minister Thomas de Maiziere had decided to reintroduce EU regulations on asylum seekers without first informing the country’s chancellor or refugee coordinator. On the surface, this behavior might seem erratic or even indicate a competition for power among German ministries taking place beneath the surface, but in reality it hints at a much deeper problem — one that could seriously undermine Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government and have wide-ranging repercussions for the rest of Europe.

The ongoing refugee crisis has overwhelmed Merkel. The German chancellor is famous for her ability to sense the direction of public opinion and adjust her policies accordingly. This time, though, many think she may have miscalculated. When asylum seekers began arriving en masse to Germany early this summer, Merkel promised that her country would receive them with open arms — and open borders. And Germans initially supported her decision, which they saw as an opportunity to show solidarity to those in need.

But as the influx of people grew, many Germans started to worry that their government had failed to assess the true magnitude of the crisis. Suddenly, Merkel was no longer the infallible leader who could do no wrong but an impulsive head of government who had put her country in danger. Some began to see the chancellor’s famous statement about refugees — “we can manage” — as proof that Berlin had lost control of the immigration problem.

What is a Geopolitical Diary?

Doubt began to build among the German people, and cracks formed within the coalition government. The center-right pushed for a tougher stance on immigration, while the center-left found itself trapped between its ideological sympathy for asylum seekers and its need to respond to voters’ demands. Conservative lawmakers who were already upset by what they perceived to be a soft stance on Greece renewed their vocal criticism of Merkel. As a result, the German administration hardened its position on migration while chaos within the government reached new heights. Questions arose about whether Merkel would be able to complete her third term, which is set to end in late 2017.

At the moment, Merkel’s position is not under threat. Even if Germany’s conservatives decide to withdraw their support, the process required to replace a German chancellor is extremely cumbersome and requires lawmakers to show that they can appoint a new government to replace its fallen predecessor. But if the center-right chooses to stop backing Merkel, the center-left probably will not be far behind. At that point, early elections would be nearly impossible to avoid.

Nobody in Germany is ready for a new round of elections, at least not right now. The popularity of Merkel’s conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU) has declined since the refugee crisis began, which has reduced the party’s appetite for an early vote. Meanwhile, Germany’s center-left is still trying to sort out its own contradicting imperatives and has no clear candidate to put forth for the chancellorship. And as the country’s major parties struggle in the polls, support for the anti-immigration Alternative for Germany party has reached a record high of about 10 percent, and attacks against immigrants are becoming more frequent. Altogether, the complexity of Germany’s current political situation means that the chances of new elections taking place in 2016 are slim.

Still, many things could happen in the coming months that would have long-term ramifications for the country and the Continent. Even if Merkel keeps her job, the ruling coalition could become increasingly ineffective, and infighting over her succession could undermine her leadership. Elections in several German regions in 2016 will test the popularity of the parties within Merkel’s coalition, and the outcome will affect their calculations about seeking early elections. Should the CDU perform poorly, party members will probably start planning for a future without Merkel.

The problem is, the CDU does not have many natural successor candidates to choose from. The only party figure who rivals Merkel is Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble, an experienced politician who lost his race to head the CDU to Merkel over a decade ago. The Greek crisis revealed a more virulent side of Schaeuble, who went so far as to suggest that Athens be expelled from the eurozone, but he has remained relatively quiet throughout the refugee crisis and has only sporadically criticized the government’s policy. With his image as the defender of Germany’s fiscal stability and economic interests, some think Schaeuble may be preparing to challenge Merkel for her post.

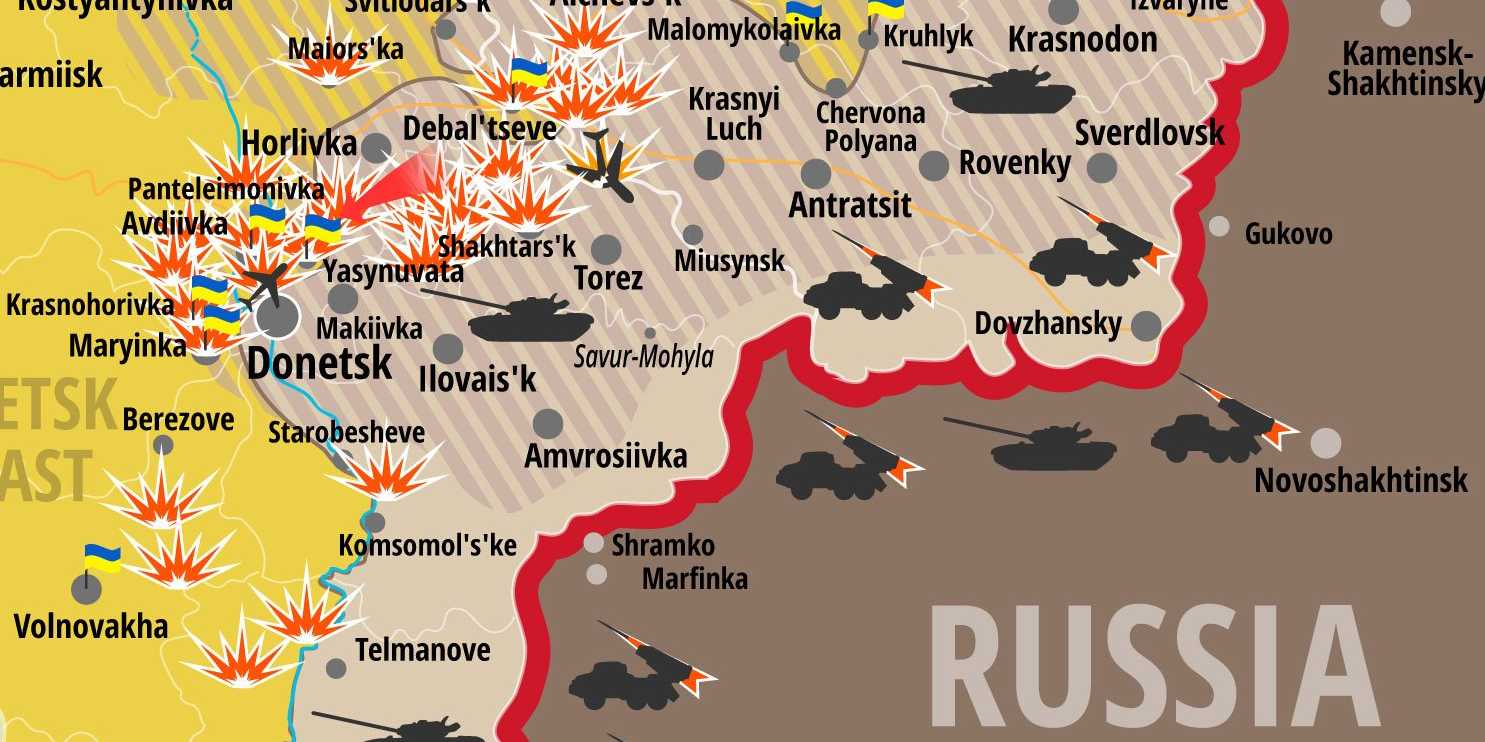

Regardless of who heads the government, though, the current situation in German politics is important for several reasons. First, a government too focused on dealing with internal disputes and preparing for new elections will be less effective in leading the European Union as it deals with a number of major issues, including heightened tensions with Russia and the migration of massive numbers of refugees. Second, the emergence of a political crisis as the already-existing migration crisis plays out could lead to a more inward-looking and Euroskeptic government. This year’s events have already debunked several myths about the European Union, from the irreversibility of the eurozone to the sanctity of open borders; if a new German government arises from the ashes of the immigration and Greek financial crises, its effects will be felt across the entire bloc.