Summary

Editor’s Note: This is the third installment of an occasional series on China’s transformation that Stratfor will be building upon periodically.

China’s Communist Party is locked in a struggle for political legitimacy. For most of the past three decades, economic growth has buoyed the party and underwritten its promises of full employment and ever-improving material conditions for the majority of Chinese. But that growth is slowing. As the country’s export- and investment-led growth model loses steam, unemployment has risen and living conditions in many parts of China have suffered, exacerbating tensions between provinces and casting doubt on the central government’s competence.

Beijing now has to rapidly expand high-value manufacturing and services industries while fostering the domestic consumption necessary to support these industries in a time of weak demand. If it does not do this quickly enough, China will face social and economic dislocation and the Communist Party will experience a severe crisis of legitimacy that may be insoluble. Many have come to speculate that China may adapt to these domestic and international pressures by transitioning to a quasi-democratic system like many of its Asian neighbors. This outcome would certainly seem likely given the features and challenges of the current government, but it is ultimately unlikely not only because of the Communist Party’s founding ideology but also, and more importantly, because of China’s status and identity as a great power.

Analysis

Stratfor has long emphasized that China’s ruling party is more resilient and its grip on power more durable than may seem to be the case. The resilience is partly rooted in successful Communist Party efforts to improve the quality of the country’s governing institutions and to extend the reach of the domestic security apparatus. It is also bolstered by the less tangible forces of nationalism andentrenched institutional bureaucracy, which bind a nation together and slow the onset of crisis. Government survival is also helped by the relative restraint that major powers have shown amid China’s economic rise and military modernization. The United States, for example, has not pushed aggressively against China’s currency revaluation, moved to constrain China’s maritime expansion or isolated China diplomatically.

Asia’s Managed Transitions

China’s situation, therefore, is one of seeming contradiction: The government is suffering an existential crisis even as its political institutions are more powerful and sophisticated than ever. The uncomfortable mixture of institutional strength and political vulnerability may seem exceptional. The history of modern East Asia, however, is replete with governments that have faced either acute or chronic challenges to their legitimacy at the peak of their effectiveness, including South Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and Myanmar. Some of these challenges were precipitated by economic crisis but just as often they were not. Most relevant for China is that each of these governments began as authoritarian, or nearly so, and ended by embracing freely contested elections that bolstered their legitimacy without undermining their power and influence. All responded with state-managed, carefully orchestrated transitions to democracy as well.

Myanmar is an emblematic — and recent — example of such a transition. From 1962 to 2011, the country was ruled by an authoritarian military government. After a managed transition, the long sidelined National League for Democracy won a resounding victory Nov. 8 in a general election that has been lauded as both free and fair. At the same time, members of the former ruling government not only retain a strong position in parliament, but far more important, continue to exert extensive influence over the country’s business community, civil bureaucracy and military, which remains Myanmar’s single most powerful institution by far. In other words, the former junta’s long-planned concession of elections and apparent defeat do not amount to true power concessions in terms of Myanmar’s long-term trajectory and evolution. In the meantime, the government has managed to garner new respect in the eyes of its own people and the international community, guaranteeing that if its leaders return to office — as they intend — they will command greater legitimacy with the electorate.

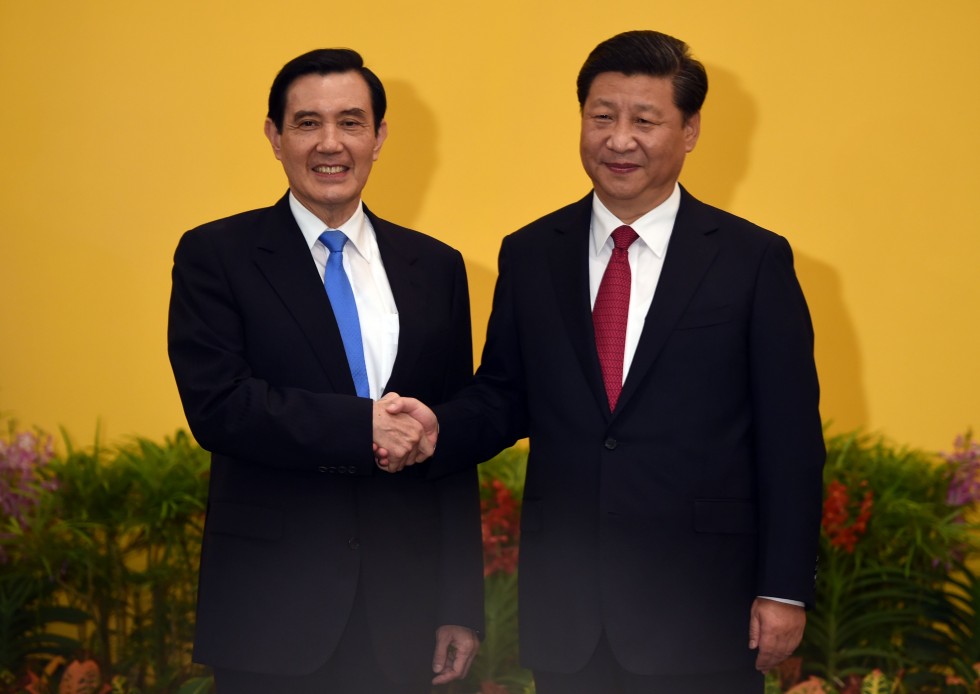

Of course, Myanmar’s military junta has followed the lead of governments in South Korea, Taiwan and Malaysia on the eve of their own transitions to electoral democracy. In each case, the entrenched political elite opted to hold elections when confronted by a confluence of declining legitimacy, grassroots political pressures and economic stress. However, these elections were structurally designed to prevent them from undermining the ruling elite’s power within the economy and bureaucracy. In Singapore and Malaysia, the former rulers won the elections and retained formal power. In Taiwan and South Korea, by contrast, the former rulers temporarily lost formal power but retained control of much of the bureaucracy. In Indonesia, the elite of the previous government never regained formal political control but continue to exert extraordinary influence in business, administration and local politics. In all cases, the old government and the elite at its helm preserved their core interests: survival and influence.

What all of these transitions have in common is that none of the governments absolutely needed to democratize when they did. This is true of China as well. These governments held immense strength compared to other domestic political parties and likely could have endured for years without change. Their embrace of elections was not reactive, but strategic. Elections staved off threats to government stability or to the safety of the elite while bolstering the elite’s long-term chances at retaining de facto control — or eventually control in name. In international terms, these governments ensured the goodwill of the United States and the many benefits of Western support.

Conceding from Strength

What about China? The potential for China’s Communist Party to follow these examples and concede to elections from a position of strength is an essential question for the future of East Asia. China possesses all the features noted above of a government on the verge of a state-managed transition to democracy. These include a strong, well-established party with a proven track record and deep pockets but a persistent problem securing the full support of the population.

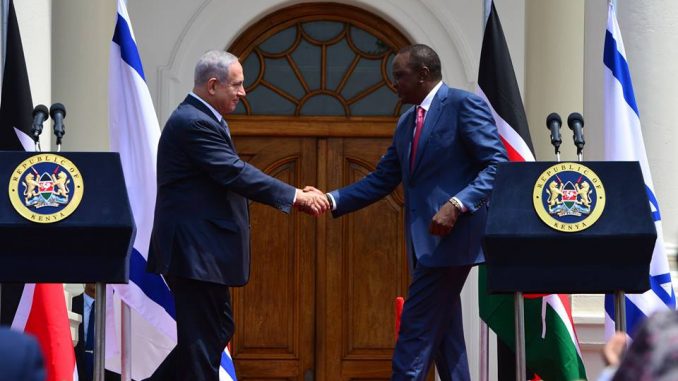

A democratic China does not seem unlikely and a managed transition would solve some of Beijing’s problems. Regular elections would offer a release for the suppressed social pressures that are difficult for China’s leaders to measure much less mitigate. Clear electoral victory would help ease Communist Party leaders’ constant fear of losing the “mandate of heaven” by quantifying the level of support that the Party enjoys at any given time. Planning for economic, security and social policy would also function differently in a democratic China, as would the management of tensions between Beijing and the provinces or between local governments themselves. Internationally, democracy would bolster China’s strategic interests, whether in Africa or Southeast Asia or North America. It would also improve China’s negotiating position with the United States, perhaps paving the way for China to accede to groupings such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

But it is its very position in the international community that prevents the Communist Party from conceding to a democratic system — a system intimately tied with the U.S.-led world order. If democracy ever comes to China, it will be once the Communist Party government has been thoroughly delegitimized through profound and sustained crisis or defeat in war. This is because of the simple fact that China, unlike Myanmar or South Korea, is a great power. With this status, Beijing sees itself as having the potential to challenge dominant U.S. power in the world system, whereas other powers are by definition secondary to the world system and must react.

The Communist Party, the entity that has elevated China to great power status, has staked its legitimacy on realizing the country’s potential to fundamentally reshape the international balance of power. This requires economic growth and good governance, but is not reducible to them. The gambit has become more pronounced and explicit in the last few years, as slowing economic growth has spurred a shift to increasing nationalism. The party’s claim to legitimacy and to being China’s rightful redeemer after a “century of humiliation” has been central to the Communist Party’s self-conception from the start. And like all rising great powers before it, China’s self-conception has become inseparable from its relationship with the system’s sole superpower, the United States. Earlier rising powers, such as the Soviet Union, understood themselves to be locked in a struggle for world supremacy with the United States. It is not ideological hatred of democracy that animates the Communist Party’s rejection of elections but the need to lay out a different path from Washington and to present China as an independent and equal pole of geopolitical power.

As growth slows and security needs mount, the Communist Party’s stance will serve to bolster popular support — nationalism feeds on external threats. In the longer run, however, it will make governing China and meeting the ever-rising expectations of its people far more difficult. To bet one’s legitimacy on nationalist aspirations is risky, especially when fulfilling those aspirations requires confronting an international order crafted by a state as powerful as the United States. Whatever the outcome, the Communist Party’s unwillingness to follow the path of other East Asian democracies and to accept the subordination to a U.S.-led order will make China perhaps less predictable to its counterparts and competitors in the coming years, but it will also make it far more interesting to watch.