December 4th marked an important occasion in Chinese-African relations, signalling, as it did, the 15th anniversary of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). This is a relationship that has been largely overlooked, and yet it is one of the world’s most significant. China is Africa’s largest trading partner by far, and trade between the two is predicted to reach $300 billion by the end of 2015. However, despite pledges by Beijing to invest $60 billion in strengthening infrastructure and development projects, there are those who have been swift to point out that China’s resource hungry nature is something less to be welcomed than to be wary of. In its greed to exploit the continent’s resources, some are asking, what might the social and environmental consequences of its policies be?

A Zambian national, labouring in one of the very poorly ventilated and incredibly dangerous Chinese run copper mines, would no doubt have his own ideas on this matter. Indeed, so cavalier an attitude do China’s captains of industry have towards their worker’s safety, that employees must work 2 years before they even get safety helmets. And woe betide those who have the audacity to rage against the machine, with sackings of obstructive union officials routinely administered; protest assemblies typically dispersed with swift and unforgiving violence. Africa’s environment has suffered little better at the hands of its Chinese investors, and illegal gold mining has led to a number of issues. Indeed, research by WACAM has shown that as many as 250 rivers in Ghana have been polluted by those cyanides and heavy metals that are a by-product of the local Chinese community’s illegal gold mining activities. To rub salt in the wound, laws introduced disallowing foreign nationals to either mine or sell gold have been circumvented by dubious practices lower down the retail chain. However, despite the evident risks associated, African governments continue to embrace vast Chinese investments in their commodity industries. In March 2015, China Hongqiao Group secured a mining and port investment deal for the development of Guinea’s bauxite reserves– the largest in the world – with the first shipment unloaded in Yantai port a mere 8 months later. While Guinea has been keen to attract investors to this highly lucrative industry, looking farther afield, the country’s desire for Chinese investment might turn out to be a poisoned chalice.

Indeed, while China’s presence on the African continent is rather new and African leaders are enthusiastic at basking in Beijing’s deep pockets, the example of several Southeast Asian countries should give them a moment of pause before popping open the champagne. Why? Because in their mad dash for resources, Beijing has turned a blind eye to the massive environmental damages done by mining companies.

Malaysia’s case is but one of these and, if it is any indication of how sustainable China’s investments in Africa are to be, then the future looks bleak. Bauxite, the most plentiful source of aluminium ore and a huge part of China’s plans to modernize heavy industry, is a hugely valuable commodity to Malaysia – raking in profits of almost $200 million in 2014. Unfortunately, industries of this value are naturally resistant to the kind of political will needed to deal with the inherent issues, where significant short term gain is inevitably made at the expense of longer term interests, especially when an industrial giant of China’s stature is cracking the whip. And the issues are significant. In areas where bauxite mining is most prevalent, there have been complaints of the sea ‘turning to blood’, a side effect of poor waste management and allowing by-products to seep into the water. In addition, road transportation of bauxite ore has led to significant air pollution, adversely affecting the health of local populations, as drivers fail to adhere to containment regulations in an industry where minutes lost are a fortune squandered. The Malaysian government has made some progress towards dealing with these and other related problems but, as observers point out, the lip service paid to the environment over the gains to be had by exporting bauxite under China’s demand has been perfunctory to say the least.

This issue is not Malaysia’s alone, however, as neighbouring Vietnam has had its own problems. The source of the world’s third largest natural deposit of bauxite, Vietnam was also a victim of China’s resource hungry policies, and while initially welcoming Chinese investment to develop its bauxite reserves, Vietnam might now be wondering whose victory this actually was. Whilst China has benefited to no end, the Vietnamese authorities have become so entrenched in efforts to protect this relationship that those who object have been met with surveillance, restrictions on their movement, and even violence. Typically, such objections revolve again around environmental concerns, with tales of “red seas”, air pollution and waste spillage once more doing the rounds. Most worryingly, Vietnam seems even less inclined to implement proper regulatory controls in an industry which is careering out of control in the wake of China’s gluttonous demand.

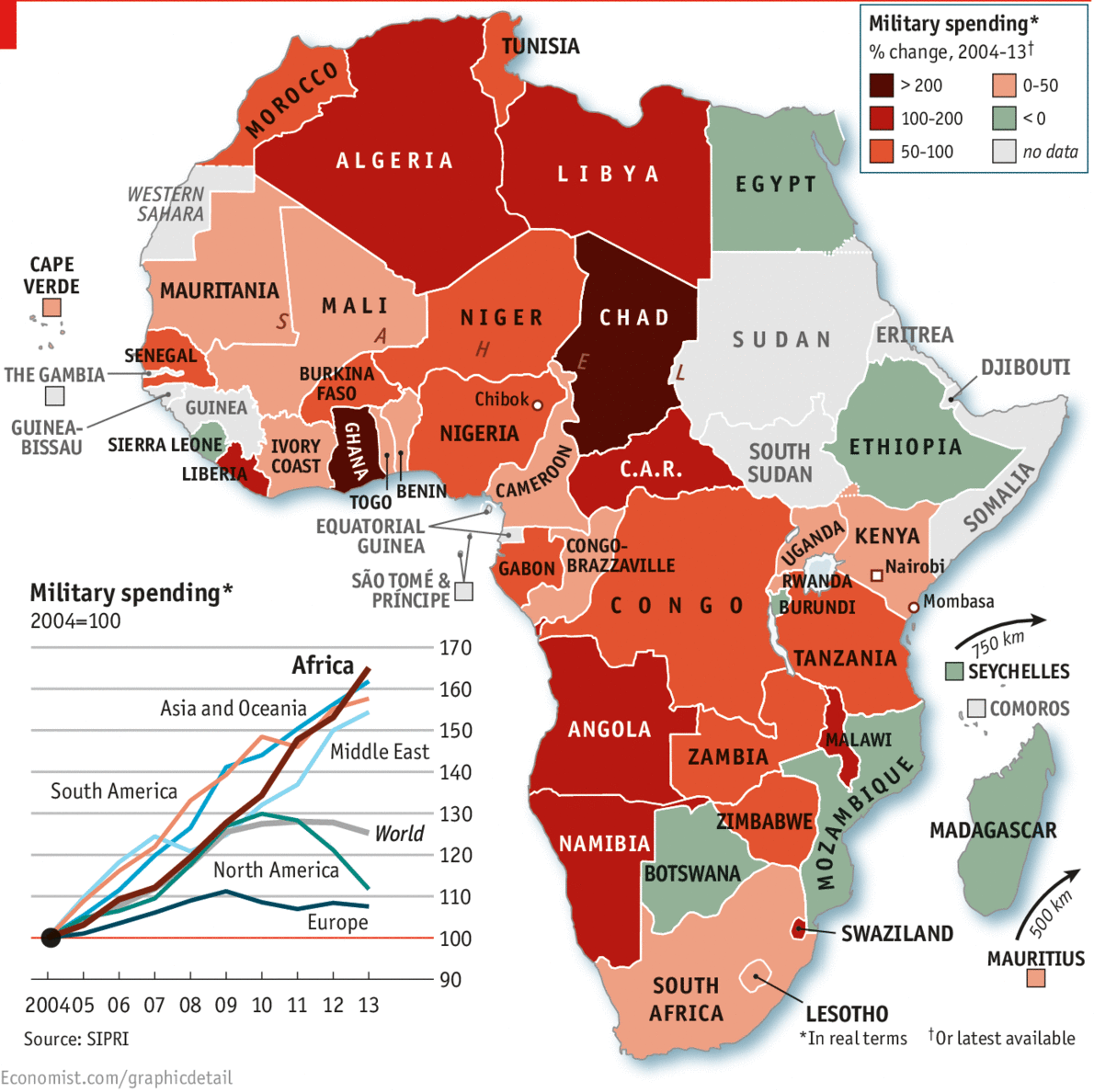

In hitching itself to China’s rising star, Africa has developed a relationship in which aspiration is no longer the pipe-dream it once seemed. With Chinese investment offering significant promises for developing African nations, cooperation with China is proving to be a significant stepping stone on the road to development. However, with the negative long term social and environmental impact that this cooperation potentially threatens – regarding bauxite mining, gold mining, or any other venture – it would wise of African governments to tread cautiously before committing to a course of action which might have entirely the opposite effect to that intended. China’s rise on the African continent might indeed provide an opportunity not to be missed, but denied the proper checks and balances it could prove less a win-win relationship. The example of Southeast Asia should be warning enough.