Bird’s-Eye View of the 9th AIPA Caucus Meeting :The ballroom was abuzz with foreign parliamentarians and staff preparing for the ASEAN Inter-Parliamentary Assembly (AIPA) 2017 caucus. Interpreter booths, cameras, and lights marked the start of two days’ worth of working group discussions. Members of parliament from the corners of South-East Asia soon settled down as the Vice Speaker for the Indonesian House of Representatives, Fadli Zon, as a host welcomed them to conduct discourse on a variety of different topics from marine security and cooperation, peaceful conflict resolution, the protection of endangered species of flora and fauna, to expanding AIPA’s capacity, subjects that are of the utmost importance to ensure the integrity of the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN).

What is AIPA?

AIPA’s efforts to tackle substantial regional issues by laying down common norms may be harder than it sounds.

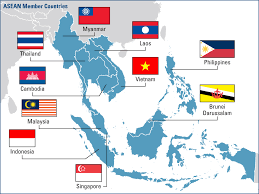

AIPA may not be as well-known as other intergovernmental organizations in the region; however, the forty year-old organization’s existence plays an important role in uniting different legislative bodies and establishing a more cohesive ASEAN by building a consensus upon which domestic bills and other legislative byproducts are based upon. Its resolutions are by no means legally binding, but it is the closest thing ASEAN has to a regional parliament. In spite of good intentions, with ASEAN’s high regard for non-intervention, AIPA’s efforts to tackle substantial regional issues by laying down common norms may be harder than it sounds.

Marine Security And Cooperation

Marine security and cooperation is an all-encompassing subject title to label the various issues states face when dealing with the seas surrounding them. One can name several issues off the bat including the traditional nation-to-nation threats such as the South China Sea dispute; man-made threats such as movement of refugees, trafficking of illegal goods, illegal fishing, etc.; and even non-traditional threats such as marine pollution. In the first working group for the caucus, Dr. Arif Havas Oegroseno, Deputy Minister of Maritime Sovereignty for the Indonesian government, stated how environmental issues cannot simply be overlooked and will greatly impact ASEAN’s future regional economy and overall stability.

It seems impossible to unravel the complexities of international marine cooperation and security in a matter of two hours, and that improbability is evident in the first working paper. Parliamentarians seem to understand that there was not much room for them to explore deeper, so instead they created a product that reiterated altruism and underlined the importance of legal frameworks (both international and domestic) that are already in place without suggesting considerable changes to the status quo.

Marine Plastic Pollution

What was perhaps notable was the extra attention given towards marine plastic pollution. Cambodia suggested that an improvement should be made to the working paper by recommending that states slowly wean themselves off of petroleum-based plastics in the course of five years. Vietnam echoed the suggestion and recommended that nations create legislations that will change consumer behaviors through proper use of propaganda, impose higher tariffs on plastic production and its trade, including develop further research on plastic alternatives and waste treatment. However, despite the much needed recognition bestowed upon the subject of marine environment, the parliamentarians seemed hesitant to propose the idea of discussing the potentially more controversial topic of marine security that would include bringing out skeletons such as drug and peoples trafficking, illegal arms trade, and more out of countries’ closets.

the parliamentarians seemed hesitant to propose the idea of discussing the potentially more controversial topic of marine security that would include bringing out skeletons such as drug and peoples trafficking, illegal arms trade, and more out of countries’ closets.

The opportunity to discuss further about security presented itself in the second working group that sat down to confer on the matter of peaceful conflict resolution. ASEAN does deserve commendation for successfully preserving a modicum of regional peace and stability since its establishment in 1967. Numerous instruments and modalities have been made to resolve differences and potential conflicts in the region. However, individual ASEAN countries have their own social turbulences and security threats that need to be addressed by the whole association to provide support, mitigate the spread of conflict and unrest to neighboring countries, or simple humanity and respect.

Ignored Regional Challenges

Parliamentarians of AIPA are aware of the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar, extrajudicial killings and terrorist uprising in the Philippines, the prospective clash with China in the South China Sea, as well as forest fires and haze that are all potential threats to ASEAN’s integrity. However, the issues were never more than whispered through the room; Myanmar’s members of parliament smiled meaningfully at Malaysia’s offer to help the Rohingya situation; unlawful killings and questionable executions were never brought up by the caucus members although the Philippines insist that conflicts must be solved through means that are “equitable and humane”; Indonesia calmly brushed off Brunei’s concern about haze; while Indonesia, Myanmar, Brunei, and Singapore refuse to commit through the working paper that the South China Sea will be resolved peacefully on the basis of international law. The only remotely admirable stance that the caucus reached (but was not specifically concluded in its final working paper) was Brunei’s proposition to help the Philippines with the strife in the Mindanao and Bangsamoro. A careful read of AIPA’s second working paper for the caucus merited the conclusion that no significant legislative recommendations were made to tackle the very real conflicts currently in the region.

During the Working Group 3, the caucus discussed the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Freeland, a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) that aims to free the world from wildlife trafficking and human slavery, graced the meeting by sharing its views on the matter. Freeland was represented by its Head of Liaison for Monitoring & Evaluation and Development Program Liaison Officer of ASEAN, Brian V. Gonzales, and Sallie Yan, Freeland’s Legal Specialist. As an NGO, Freeland is an ideal partner for the governments of ASEAN member states, and AIPA MPs especially, to work upon the intricacies of implementing CITES. Non-governmental organizations in the region can provide valuable on-the-ground insight as well as objective critique to states’ policies on the transport and trafficking of endangered plants and animals. AIPA would do well to continue exploring the many opportunities for collaboration with related NGOs.

Through the report each parliamentarian made on how their country has adopted CITES into their own national laws and regulations, some member countries have gone as far as establishing ad hoc courts dedicated to cases pertinent to environmental crimes, including wildlife-related violations. What exacerbates the issue of wildlife trafficking is the convoluted supply chain of cross-border transactions. In response to this reality, the meeting proposed a creation of a special joint task force to tackle illegal trade of wildlife and plants such as the Siamese Rosewood within AIPA member countries. This action point and previous domestic measures exhibit a degree of commitment from member countries on the matter of CITES to tackle the insidious issue of wildlife trafficking and preserve particular endangered species from exploitation.

Moreover, the meeting also included a special session on developing AIPA’s capacity as a regional forum of parliamentarians. Isra Sunthornvut, the Secretary General of AIPA, initiated the open discussion by admitting that AIPA is at a crossroad. It needs rejuvenating, rebranding, and revamping in all of its aspects, including the relevance of its existence for the past four decades. It is apparent that AIPA, as an institution that complements ASEAN, is showing signs of a mild existential crisis.

Considering the essence of the institution as the representative of the ASEAN people, it is ironic that the public seems to know so little of the assembly. It is obvious that AIPA is not getting the amount of exposure it needs. Even some of the present ministers of parliament (MPs) during the caucus confessed that they had very little knowledge of AIPA before being actively involved in the institution. As the Indonesian proverb goes like “Tak Kenal Maka Tak Sayang (Unknown therefore unloved)”, in order for the people and its MPs to be concerned about and prioritize AIPA, it is obligated that they get acquainted with the institution itself. Mainstream media coverage should be encouraged along with the engagement of civil society organizations, NGOs and the public in general through the well-implemented social media strategies.

Consensus?

Achieving consensus on the final results of the caucus was by no means easy, but the reports will be useful resources for AIPA’s General Assembly. The arduous process also illustrates that open discussions, which allow each MP to voice their concerns, can democratically yield results. Although perhaps not the best resolutions by the end of the day, it is enough to signify that every member has a different voice and has the opportunity to give valuable contributions to ASEAN’s foundation as a regional international organization that prides itself for its cooperation, solidarity, and unanimity.

In light of its most recent caucus, MPs seem to have bitten off more than they could chew during the ninth AIPA caucus: the topics were much too broad and all-encompassing to be effectively resolved in such a brief amount of time and AIPA’s limitations makes constructing adequate recommendations a game of skirting around the principle of non-intervention with a dash of diplomatic propriety. In spite of that, it must be noted that international governance is by no means easy even on a relatively small regional scale such as ASEAN. If ASEAN countries want to continue to work together seamlessly, respective domestic laws and regulations need to be in sync for a common regional development; thus, even though AIPA may be far from being a regional parliamentary body such as the European Parliament, its role is still imperative. It has to anticipate future obstacles and respond to current difficulties by providing concrete and specific legislative recommendations that are clear-cut but still malleable enough to fit the different needs of its member state. At the end of the day, AIPA has so much more to give to ASEAN than simply as an advocate of good intentions.

By: Rizkina Aliya & Ardy Nugraha

ISAFIS 2017