In the early 1990’s, Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori started a process of free-market reforms after strong tensions among the former President Alan Garcia and the US government and International Financial Institutions as well. Fujimori’s political and economic reforms reconfigured the structure of Peruvian economy under many of the principles of the so-called Washington Consensus.

These reforms pursued to integrate the country into the international economy, to put an end to a 10 year long armed conflict against domestic terrorist groups, reduce the State intervention in national economic and social affairs, and establishing a system of self-regulating supply, demand, and pricing mechanisms as well.

Peru’s 1990’s reforms coincide with a favourable trend to open-market policies in Latin America, in a moment when around the hemisphere appeared new and great expectations about the creation of a ‘neo-regionalist’ model of integration under free-trade patterns. As we already mentioned, some milestones in this direction were the creation of MERCOSUR in 1991, as well as the CAN and the WTO in 1994.

However, unlike other countries like Chile or Argentina that were in the middle of their own democratic transition processes, Fujimori consolidated his authoritarian government after the dissolution of the Peruvian Congress in 1992 and the elaboration of a new Constitution in 1993. The concentration of power by the President in the early 1990’s, helped him to promote his reforms freely without major resistance from opposition parties, trade unions or civil society actors.

Figure 1: President Alberto Fujimori announcing the dissolution of the Peruvian Congress, as well as the intervention by the Executive Branch in all major institutions, like the Judiciary, the Ombudsman, and the Tribunal of Constitutional Guarantees (1992). Source: América TV.

Fujimori opened all sectors of the Peruvian economy to Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and lifted restrictions on remittances of profits, dividends, royalties, access to domestic credit, and acquisition of supplies and technology abroad. In addition, the government offered tax-stability packages for foreign investors for terms of ten to fifteen years and implemented wide-ranging privatization programs that offered international investors investment opportunities; eliminating competition from state-owned and domestic firms that enjoyed clientelistic or material advantages. However, it is important to point that the privatization process was Fujimori’s authoritarian project keystone. Under the argument of the need to create a business-favourable environment, Fujimori sold most of Peru’s strategic assets and undervalued State-led companies guided only by short-term considerations, without a coherent strategy. After selling 68% of electricity, 35% of agriculture, 90% of mining companies, 85.5% of manufacture industry and 68% of Hydrocarbons, Fujimori’s government obtained USD 9,221 million. However, from the overall amount obtained by privatizations, only USD 6,445 million entered into the public coffers. That money was used to buy military machines, the payment of the external debt (forbidden by Peruvian Law), and for clientelistic social spending in order to gain domestic support.

After Fujimori’s fall in 2000, the Peruvian market-oriented reform process was ‘deepened’ through the signing of a Free Trade Agreement with the United States, where various issues relating to state intervention in the economy, property rights and governance were included. We identify four reasons about why Peru decided to engage in a bilateral negotiation with the US instead of operating through multilateral organizations like the WTO or the Andean Community:

At the global level, the stagnation of the post-Uruguay Round negotiations, which initially proposed the total liberalization of World trade. The failure of the WTO summit in Seattle (1999) and the long agony of the Doha Round were the main global reasons of why countries pursued less ambitious and more regional-focused agreements.

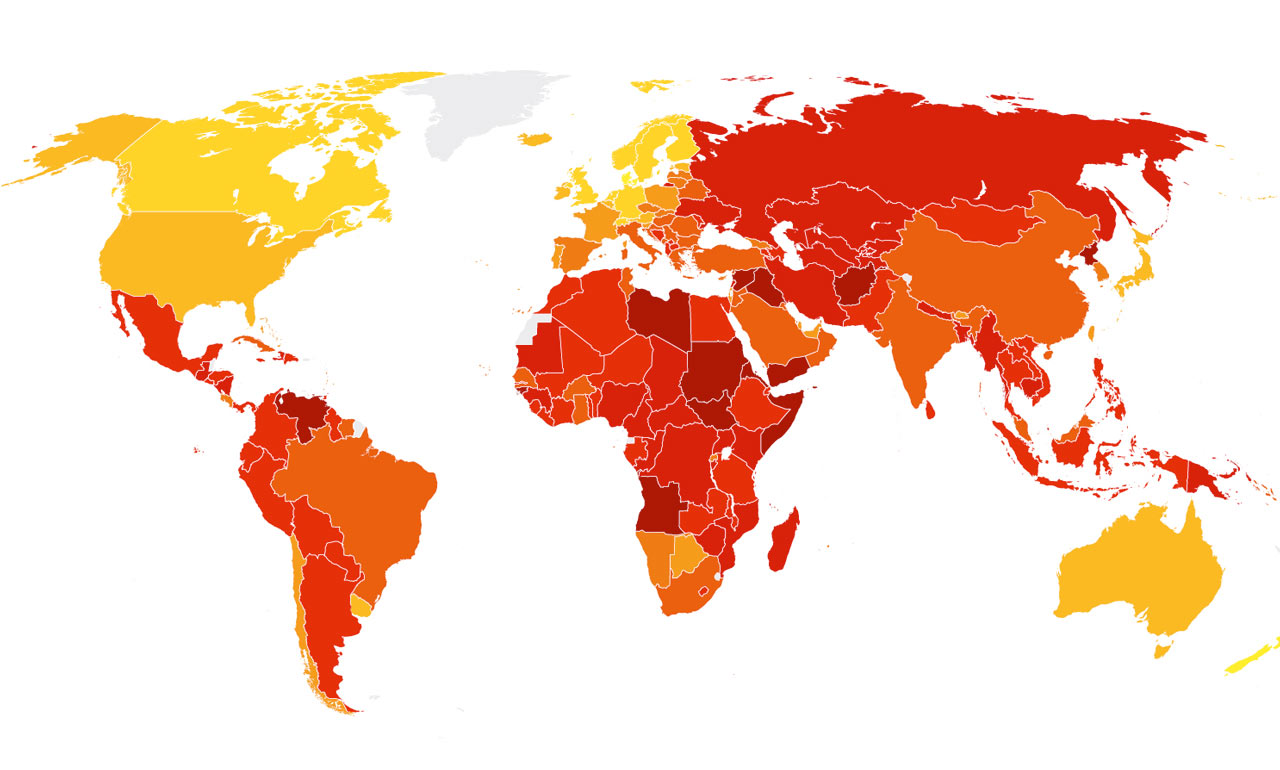

The failure of the United States to obtain consensus in Latin America to create a free-market space that encompasses all the Western Hemisphere (except Cuba). Designed as an ‘expansion’ of NAFTA, the so-called Free Trade Agreement of the Americas (FTAA), seek to promote an unified set of rules in issues like tariff reduction, barriers and access to markets, trade of goods and services, FDI, privatizations, agriculture, intellectual property rights, subsidies, antidumping measures, free competition and resolution of disputes. The potential capacities of such trade area would encompass a population of at least 800 million people and a GDP of USD 8.5 billion. Nevertheless, due to internal resistances coming from the US and the Latin governments (for different reasons), the agreement would never been signed. In the US, the Congress opposed to authorize President George W. Bush to use the ‘fast-track’ mechanism for trade negotiations without a previous surveillance and approval by the House and the Senate. In Latin America, the left-interventionist group of countries (Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador) with the support of Brazil and Argentina, criticized the US intentions to establish a FTA while keeping at the same time protectionist measures due to ‘domestic politics concerns’, like antidumping measures, agriculture subsidies, President Bush’s lack of interest on environmental issues, as well as the ‘democratic clause’ of the draft proposed by the US with the objective to exclude Cuba from the agreement. Finally, the FTAA was definitively rejected in the 2005 Mar Del Plata Summit of the Americas, when the deadline for the signing of the agreement was settled.

Figure 2: Former Presidents from Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela in the Cumbre de los Pueblos in Mar del Plata, Argentina. (2005). Source: Telesur.

At the regional level, there was a profound disagreement among the CAN country members due to ideological and economic reasons. In parallel with the FTAA negotiations, the Bush government was also trying to pursue less ambitious, but more geographically focused agreements with the already existent integration organizations, like the CAN. While excluding Venezuela due to President Bush’s sour relations with President Hugo Chávez’s, the US tried to establish an Andean Free Trade Agreement with Peru, Colombia, Bolivia and Ecuador. Because of the interest by Peru and Colombia to negotiate with the US directly without caring about the concerns of their Andean partners (Especially about biodiversity, environment and labour issues), the Venezuelan government declared ‘the death of CAN’, and asked to leave the organization in 2006.

Figure 3: US President George W. Bush and Peruvian President Alejandro Toledo in Lima, Peru. (2002). Source: Peru.com

At the domestic level, the export-oriented Peruvian economy was experiencing a slow, but uninterrupted recession process since 1998. Furthermore, the lack of juridical and political stability did not create incentives to attract new FDI; and a not-reliable instrument regulated the trade regime with Peru’s most important partner: the Andean Trade Preferences Drug Enforcement Act (ATPDEA). Even if this agreement gave most Peruvian products a preferential access to the US market without tariffs, it was not a reliable instrument to attract FDI. The ATPDEA needed to be renewed each 3 years, and it was conditioned to Peru’s support of the US War on Drugs in the region. Of course, the American Congress was able to deny a renewal if they feel that Peru was not ‘keeping its compromises’; not only in the drug fighting but also in other non-narcotics issues like intellectual property rights.

About the Author :

By: Anthony Medina Rivas Plata

Peruvian. Master in Public Policy by Erasmus University Rotterdam and the University of York. He currently works as Director of International Cooperation at the Institute of Andean Political Studies.