By Eugene Chausovsky

Twenty years have passed since famed political scientist Samuel Huntington published his seminal work, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. To anyone interested in international relations, the book is as relevant today as it was when it was published in 1996, if not more so. It not only anticipated many of the conflicts that took place after the Cold War, but it also fitted them within a context that was starkly different from the view that was widely held at the end of the 20th century: that a more peaceful, democratic and liberal world order was upon us.

Yet The Clash of Civilizations failed to fully grasp and appreciate many of the important drivers of the post-Cold War global system, rooting itself in a civilization-centric perspective rather than adopting a more encompassing and nuanced geopolitical model. And so, 20 years later in a world that seemingly confirms Huntington’s predictions in many ways, it is just as illuminating to take a closer look at what he got wrong.

Analysis

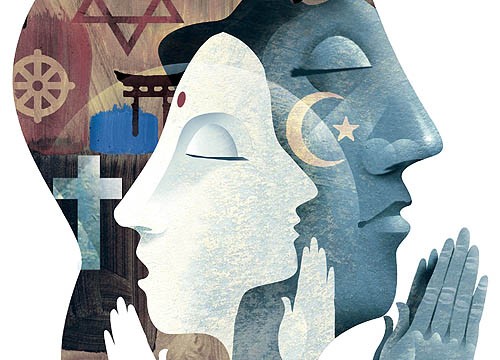

Huntington believed that the ideological conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union — the Cold War era’s two superpowers — would not mark the “end of history,” as so many believed, but that it would eventually be replaced by a conflict between civilizations in the post-Cold War world. Huntington defined a civilization as the broadest level of shared identity between groups of people, and he divided the world into nine of them: Western, Orthodox, Islamic, African, Latin American, Sinic, Hindu, Buddhist and Japanese. It was these civilizational divides, Huntington argued, that would shape the relationships between states after the Cold War came to a close.

Within this broader framework, The Clash of Civilizations described a number of key themes, two of which are especially relevant to the current state of the global system. The first predicted that Western civilization (primarily made up of the United States and Western Europe) would find itself increasingly challenged by non-Western civilizations, especially the Islamic world and China. The second forecast that the fault lines between civilizations, the geographic areas where two or more distinct civilizations are in proximity to one another, would be major sites of conflict in the post-Cold War era.

Challenges to the West Grow

Huntington contended, in what was perhaps his most forward-looking insight, that clashes between the West and the Islamic world would intensify with the collapse of the Cold War rivalry. He astutely observed that the fall of the Soviet Union and much of the global communist movement in the early 1990s “removed a common enemy of the West and Islam and left each the perceived threat to the other.” Huntington argued that the shared universality of the Western and Islamic cultures, which espouse views that they believe all humans can adhere to, would generate competition and conflict between the two. He even went so far as to identify the manner in which this conflict would play out: “a war of terrorism versus air power.”

Support for Huntington’s theory came on Sept. 11, 2001, when al Qaeda launched its attacks against the United States and prompted the subsequent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. These events set Western powers on a collision course with many countries and groups within the Islamic world as the rise of radical Islamist militancies coincided with the United States’ becoming mired in conflicts throughout the Middle East. While the way in which the United States conducts its global war on terror has evolved over the past two decades, there is no question that a dynamic similar to the predicted Islamic-Western conflict has become an important driver of the modern world order. Indeed, the Islamic State’s recent attacks in Paris, which came amid increased Western airstrikes in Syria, seem to suggest exactly that.

That said, the tremendous diversity within the Islamic world serves as an important counterargument to Huntington’s theory. Islam is a faith with more than 1.3 billion followers around the world. They live under kings and presidents, prime ministers and caliphs, and in many cases they have less in common with each other than they do with their non-Muslim counterparts. One could argue that countries such as Tunisia, Malaysia and Turkey have more in common with the West than with Afghanistan or Saudi Arabia. The problem with Huntington’s concept of a broad civilizational clash between the Islamic world and the West is that it assumes there is a single, unified “West” and a single, unified “Islam,” when in fact the distinctions and variations within both worlds are myriad. And just as Huntington overstates the civilizational nature of conflicts in the Islamic world, he fails to address many of the geopolitical imperatives behind them, including the opening of fissures within Islam as the Sykes-Picot era declines and the weakening of centralized states’ ability to contain those divisions.

While Huntington attributed the Islamic world’s rise to its demographic expansion, he credited the post-Cold War ascent of China to its economic expansion. At a time when China had only begun to emerge as a major economic power, Huntington described it as a country that was “gradually emerging as the society most likely to challenge the West for global influence.” He argued that China would ultimately translate its growing economic strength into political and military might, which Beijing would then use to challenge the United States’ dominant position in East Asia.

Like the Islamic world, the Sinic civilization believes itself to be superior to the West, and Huntington predicted it would therefore seek to challenge the West and its designs for global influence. China’s resistance to Western supremacy stems from its Confucian values, which emphasize the importance of hierarchy, authority, consensus and the state’s dominion over society and which clash with American beliefs of liberty, equality, democracy and individualism. The chasm between the two makes a Western-style political structure incompatible with Chinese cultural and civilizational traditions, just as it is incompatible with the Islamic world’s rejection of the separation of church and state. As a result, the relationship between the two civilizations would become increasingly confrontational, especially as China’s economic and military power expands and Beijing begins to pursue a role as a regional hegemon.

The prediction that tension between China and the West would grow after the end of the Cold War has certainly come true. But Huntington’s reasoning behind it is less convincing. Confucianism is not what has created friction between China and the United States; trade and economic patterns have. In much the same way, it was not a unique Japanese culture that brought it into conflict with the rest of Asia and the United States during World War II, but more fundamental geopolitical interests such as securing supply lines for an economy that was heavily dependent on raw material imports. In Stratfor’s view, place matters far more in shaping the global system than does wide-reaching and all-inclusive themes like a civilizational clash.

Volatility at the Fault Lines of Civilization

In a separate but related point, Huntington speculated that conflict between the world’s different civilizations would flare up on the borders separating them. And in the years immediately following the Cold War, he had a number of examples to draw from. In the early 1990s, the Yugoslav Wars erupted, pulling Orthodox Serbs, Catholic (Western) Croats and Bosniaks into a bloody battle fought along civilizational lines. Not long after, the predominantly Orthodox Armenia and mostly Muslim Azerbaijan declared war over Nagorno-Karabakh, and both sides received outside support from patrons within their civilizational categories: The Turks backed their religious and cultural brethren in Azerbaijan, and the Russians came to the aid of their Orthodox comrades in Armenia. Each of these cases seemed to offer recent evidence that supported Huntington’s theory.

But Huntington also predicted that clashes would take place in other areas, with the caveat that tensions would likely simmer under the surface for a while before eventually materializing as conflicts. One such place was Ukraine, which he described as a “cleft country with two distinct cultures,” adding that “the civilizational fault line between the West and Orthodoxy runs through [Ukraine’s] heart and has done so for centuries.” He raised the possibility that Ukraine could “split along its fault line into two separate entities, the eastern of which would merge with Russia.”

This appears to be extremely prescient today, since Ukraine has, in a de facto sense, split after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the outbreak of separatist conflict in the country’s east. But using the same civilization-centric logic, Huntington also predicted “if civilization is what counts … violence between Ukrainians and Russians is unlikely.” He went on to conclude that the most likely scenario was a Ukraine that remained whole and independent, if divided, and that cooperated closely with Russia. The events of the past two years clearly call this forecast into question, showing instead that violence between Ukrainians and Russians is in fact possible and that the catalyst of their conflict reaches well beyond civilizational differences. Instead, it is a struggle shaped by geopolitical interests: Russia’s imperative is to secure a buffer zone in the former Soviet periphery, while the United States’ imperative is to deny Russia that buffer and prevent the rise of a hegemonic power in Eurasia.

What He Got Right

The failure of The Clash of Civilizations lies in its attempt to present civilizational differences as an all-encompassing explanation of global conflict. But this is not a viable model to use, at least on its own, to understand today’s world. Instead, geopolitics, which does not subscribe to any particular universalistic theme but examines how geography intersects with the political, economic, security and cultural ties within and between societies, is a far more effective way of analyzing international relations.

Still, this is not to completely discredit Huntington. The Clash of Civilizationsholds many insights that provided useful context for a good share of the conflicts that have taken place over the past 20 years and remain relevant to this day. With an eventful and volatile 2015 behind us and 2016 ahead, one of these insights is especially worth considering:

“Instead of promoting the supposedly universal features of one civilization, the requisites for cultural coexistence demand a search for what is common to most civilizations. In a multicivilizational world the constructive course is to renounce universalism, accept diversity, and seek commonalities.”

Of course, searching for common values and accepting the differences of others will not fully eliminate conflict, which has existed throughout human history and will continue to do so. But any effort to mitigate it in an increasingly dynamic and unpredictable world is surely, as Huntington argues, one that is worth pursuing.