Summary

Feb. 27 marks the anniversary of the assassination of Russian opposition heavyweight Boris Nemtsov. His killing sparked two weeks of intrigue in Russia’s top political circles, laying bare previously obscured Kremlin infighting and putting President Vladimir Putin’s continued control in question. The dispute, which went far beyond the death of one opposition leader or even broad factional competition, was in fact a struggle over who controls Russia’s future. In this it mirrored a three-year period of division in the early 1920s that ended in a leadership transition and set the trajectory of the Soviet Union.

Analysis

Struggles among the Kremlin elite are as old as the fortified stone citadel itself. The name Kremlin literally means “fortress inside a city,” a potent metaphor for the murky elite power struggles at the heart of Russia’s bustling government system. For the past decade, the Putin government has been divided into four camps: the powerful Federal Security Services (FSB), the so-called liberal reformists, the hawkish non-FSB security circles and a circle of those who are loyal to Putin alone.

These clans are constantly competing for power, assets and influence, with Putin playing the role of arbitrator. At the moment they are balanced — no one clan can change the power at the top. Russian history has shown, however, that this can change quickly. The pattern in recent years has held steady, with the FSB squaring off against the other clans and even against Putin himself in some cases.

Ukrainian Roots

The story behind the Nemtsov assassination begins with the 2014 Euromaidan uprising in Ukraine a year before. The popular protests that ousted Kiev’s pro-Russia government took Moscow by surprise. Russia’s deep networks of influence unexpectedly failed to prevent a change in government, and only a sliver of eastern Ukraine rose up in defiance of the pro-Western government. For Kremlin insiders, blame for the failure fell squarely on the shoulders of the FSB, which held the main portfolio responsible for influence and intelligence inside of Ukraine. As a result, the FSB briefly lost its lead position overseeing Ukraine and, moreover, Putin reportedly restructured the group shortly thereafter.

This put the FSB on its heels, spurring it to engage in a series of power grabs that gave it control over key positions and increased its reach within various security circles. Toward the end of 2014, Putin’s control over the FSB also came into question. His behavior became increasingly odd as he missed major press conferences and spent his birthday alone in the Siberian forest. Putin ultra-loyalists among the Kremlin elite, particularly Chechen President Ramzan Kadyrov, rallied around their leader, flooding social media with messages of support. The Chechen leader also gathered 20,000 troops from his infamous Chechen Brigades to support Putin and suggested deploying them directly to Ukraine.

The clash between Putin’s cadre and the FSB escalated in 2015, culminating in two full weeks of disarray in the Kremlin. Nemtsov’s assassination on Feb. 27, 2015, was part of this. Authorities then arrested a ring of Chechens connected to Kadyrov for the murder, and Putin canceled his trip to Kazakhstan, disappearing from public view for 10 days. Russian media went into a panic, speculating that illness or even a coup had taken Putin out of commission.

These high-profile power struggles added to the standoff in Ukraine. The start of an economic recession in Russia at the end of 2014 worsened the situation, creating a perfect storm for Putin. Today, Kremlin elites are still divided along the lines that emerged from the Ukraine crisis, disagreeing over both who should be in power and how to tackle Russia’s various crises. Putin is still trying to manage these swirling controversies.

Stalinist Parallels

The current situation in the Kremlin bears distinct similarities to the period that saw the rise of Josef Stalin to replace Vladimir Lenin, a long process that was cemented in 1924 with Lenin’s death. Lenin had ridden to power on the back of the Bolshevik Revolution, which stemmed from Russia’s catastrophic role in World War I and collapse of the Tsarist system. As the Bolsheviks consolidated power in the early 1920s, they had to manage continual famines and an economy in shambles. Lenin ruled in conjunction with a system of elites who were rough analogues of the current Kremlin clans. Those in power were assiduous in moving to secure control over economic assets before the civil war among the Reds, Whites and an array of different forces had even ended. In fact, Lenin had begun his process of ruthless economic and political centralization as early as 1918.

But when the civil war ended and the Soviet system began to take shape, the elites within the Kremlin became deeply divided over what sort of economic system should come next. The region under Russian rule was in disarray, ravaged by war and blighted by famine. The Kremlin needed to catch up with the other great powers but was unsure how to rapidly modernize Russia’s industrial sector. In another parallel to today, the main split was between those who wanted to pursue further centralization and those who wanted to reverse course and liberalize the economy. Lenin came down in favor of a more open economic system, warning that Russia is “being sucked into a foul bureaucratic swamp” of entrenched corruption.

Elites were similarly divided about policies in Russia’s near abroad — much as Kremlin clans are today. In what came to be called the Georgian Affair, in 1922 Stalin proposed absorbing all the Caucasus states — Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia — into the Soviet Union in one overarching republic. His motivation was to prevent those populations from consolidating local power and challenging Moscow. Lenin accused Stalin of trying to create a “Great Russia,” a historical concept that advocated that Moscow control all the lands of Rus, especially the ethnic and linguistically related populations of Ukraine and Belarus. Stalin won the debate, although Lenin continued to push his point in the years up to his death.

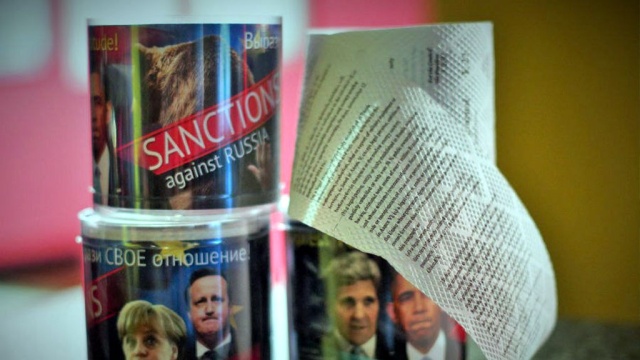

Similar concerns about Russia pushing beyond its borders undergird the ongoing dispute over Ukraine policy. For the past two years, Putin and many within the conservative non-FSB security circles have evoked a concept similar to Stalin’s Great Russia, Novorossiya. The idea has its earliest roots in the ousting of the Ottomans by the Russian Empire and encompasses the swath of territory that includes southern Ukraine, modern day Transdniestria and the Donbas. Ultraconservatives in the Kremlin originally wanted Moscow to militarily capture all of Novorossiya, though Putin instead decided on a somewhat more moderate approach: annex Crimea and maintain eastern Ukraine as a semi-frozen conflict. Many are still pushing him to launch a full-on military intervention in Ukraine. However, the Kremlin’s liberal circles have begun advocating a pullback on actions in Ukraine so sanctions can be lifted and the Russian economy can heal.

In the 1920s, the similarly divided elites shored up their respective positions. As Lenin’s health declined, he continued to denounce Stalin as an unsuitable successor both within the Kremlin circles and in his written testament, which detailed his view of where the country should go. But Stalin had already started to groom loyalists behind Lenin’s back and isolate Lenin from key decision-makers under the pretext of Lenin’s illness. Toward the end of Lenin’s life, there was a dilemma within Stalin’s circles over whether to move against the iconic revolutionary. This led to wild vacillations of position and loyalties among the elites until Lenin’s death and Stalin’s consolidation.

Infighting among the Kremlin factions is similar to that seen in the Stalinist circles of the early 1920s. Putin has long been the uniting factor within the Kremlin, arbitrating among the clans, but now he seems increasingly isolated. Over the past year, Putin has encircled himself with ultra-loyalists and distanced himself from power players such as the FSB. One of the greatest factors keeping the Kremlin clans from moving against Putin is his extraordinary popularity among the Russian people. With myriad problems plaguing Russia, Putin is still the only elite able to appeal to the dissenting points of view — at least for the moment.

The echoes of the 1920s do not mean that Russia is going to witness the rise of another Stalin but that the Kremlin is in a period of division that makes it unclear precisely who is driving Russian strategy. Putin implemented a system over the past 15 years to stabilize Russia following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the chaotic years under former President Boris Yeltsin. This is much like the Soviet system, which attempted to stabilize the union following war, the fall of an empire and a revolution. But cracks in the system are surfacing, and Putin’s ability to continue driving a united regime is in question. It is an uncertain period for Russia — on its borders, within the homeland, and inside the Kremlin itself.