An accord with Moscow could end liberal democracy in Eastern Europe as well as America’s values-based foreign policy. By

The Russian hacking scandal of the Democratic National Party continues; accusations that incoming President-elect Donald Trump is a Russian stooge are as steady as the drumbeat of yesteryear’s cries that Barack Obama was not really a citizen. The evidence behind the attack is still thin. Yet it is also irrelevant because it seems the incoming administration has concluded that an alliance with Moscow is just what America’s geopolitical doctor has ordered.

A Russo-Trump alliance is in the offing and it does make a lot of sense in the short term.

Alas for the international system, and for the United States, it’s a deal with the devil that will exact ever-higher tolls the longer it goes on.

Going beyond Trump: The Republican Party is ready to be led to the arms of Vladimir Putin in exchange for burden sharing against Sunni supremacism

The US has been fighting Sunni supremacism for fifteen long, expensive years. It has a shaky ally in Afghanistan, propped up by just under 10,000 US troops who hold together the Kabul urban regime but little else. It has been forced back into Iraq and somewhat into Syria; its military is deployed against Sunni supremacist forces in Libya, Yemen, Somalia and, for now, the Phillippines.

That war-weariness has set in on both sides of the political aisle in the United States is rather reasonable. But the hyperpartisanship of today’s generational Strauss-Howe Crisis has meant that sides were willing to endure sacrifice so long as it’s their side demanding it.

That was, and is, not a politically sustainable model: someone must eventually find a cheaper way to wage war on Sunni supremacism to pave the way for the next era of good feelings coming in the mid- to late-2020s. That will be a time that demands consensus, not bickering. And so now is the time to put forward proposals for that consensus.

And so the GOP, led by Trump, is proposing a Russo-American grand alliance to annihilate Sunni supremacism.

After all, this has been done before: despite deep ideological animosities, the USSR and United States combined to destroy fascism in World War II. (The House Un-Aamerican Activities Committee, a communist witch hunt, began in 1938, just two years before America would be forced to share not just kind words but actual tanks with the much-maligned Soviet Union).

The ideological gap is not so great this time around. Putin’s authoritarian ideology hinges on Russian imperial nationalism and crony capitalism, measures he takes to preserve his own power and the current borders of the Russian state. Moscow does not, at least for now, aim for world domination.

And both the US and Russia hate and fear Sunni supremacism

The United States is not about to fully abandon the Middle East, tempting though that is for the superpower’s citizens. It must continue to secure energy supplies for its allies in Europe and Asia; it is now hyper-aware that conflict in the Middle East can spill over to crucial allies in Europe in the form of both refugees and terror attacks; and its elites, short-sighted though they can be, are still dimly cognizant that forces in the Middle East want to create an anti-American Islamist superpower, whether led by Tehran, Mecca, Cairo or Ankara.

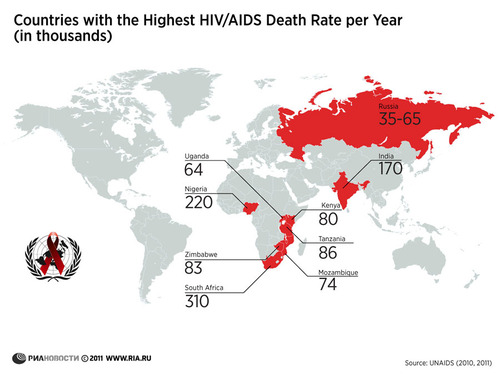

The Russians don’t have the energy need. “No blood for oil” is not a clever protest slogan in Moscow. Instead, Russia fears spillover conflict into its own Muslim regions. Forget not that a Russian airliner full of tourists was downed by the Islamic State in just 2015. The litany of Sunni supremacist attacks in Russia itself is long.

Moreover, the same proto-superpower that might just emerge from the Islamic world should it be left alone could menace Russia. Putin specifically fears his Muslim population, some of whom agitate peacefully for secession, others violently. He fears that Islamist influence could topple his friends in Central Asia, right up through Kazakhstan, making an already tough border even harder to hold.

This overlap of interests has been around since at least 1999, when Russia and America both suffered their first waves of major Sunni supremacist attacks. When the US invaded Afghanistan in 2001, Russia, which only 25 years before had been fighting a proxy war against Washington there, provided logistical support.

It’s the reason that Iran, and not Russia, was the primary conduit for insurgent weapons during the US occupation of Iraq. It’s the reason why Putin never avenged the Red Army’s blood in Afghanistan by arming the Taliban. It’s also partially the reason Russia decided, in late 2015, to storm into Syria and save the ostensibly secular Assad regime.

But why Russia? Why not force NATO states to spend more in guns and blood?

Trump has, of course, muttered about this. But US elites, including Republicans, still seem aware that a disarmed Europe is one that benefits the United States. Returning Germany to traditional geopolitics is certain to bring a major challenge to the US. Europeans themselves have become so inured to being defense free riders that few want to rearm enough to be a major partner in war. Thus US elites don’t particularly want to rearm Europe and Europeans don’t have much incentive to do so anyway.

But Russia remains armed and increasingly capable. Having leveled Grozny in 1999 in its first major anti-guerilla war, Putin’s propaganda machine has projected a Russian military both capable of winning big battles and immune to human rights watchdogs. If Chairman Mao is right and guerrillas are fish in the sea, then Putin has taken a line from Guatemalan president Efraín Ríos Montt and is draining that sea. The bombing campaign on eastern Aleppo makes sense in those terms.

This is a fascinating aspect of both fake news and propaganda: by all measures, the United States is better at both counterinsurgency and anti-terrorism. It can project power in multiple theaters; it’s doing what Putin is in Syria in both Afghanistan and Iraq and has been doing so much, much longer. It’s applying a lighter but still formidable touch in three other countries: Libya, Somalia and Syria. This is while it’s facing down a rising China in Asia and Russian adventures in Eastern Europe.

But Putin’s Russia has managed to win the information war. Not a huge surprise, given Putin’s KGB background, yet effective nonetheless. It looks like Putin is more capable when he’s still a weaker partner whose hands are largely tied. It helps that Putin is applying a lot of force on just a small set of locations. Your aim always seem better when several guns are firing at just one spot.

And so a combination of perceived and actual strength is why the GOP is now ready to gamble on some kind of alliance with Moscow against the forces of Sunni supremacism.

And yet short memories make for repetitive stories

As noted above, this has been done before. The Allies made a deal with Stalin in an hour of dire need. As the GOP and Trump does now, they misread Russia’s needs and intentions. Their combined forces overthrew Hitler’s legions and won World War II in Europe, but the price was a Soviet Eastern Europe and 45 years of nuclear-armed hostility that gave life to numerous proxy wars around the world.

Russia as it exists today must have a secure western frontier: the further west into Central Europe, the better. Russian state psychology does not allow for a benign western flank. Too many betrayals, too many graves, for that kind of thinking. A distant Islamist superpower is threatening, but not nearly as threatening as a democratic NATO and EU. These are both a direct strategic threat to Russia’s heartland and a direct political threat to Putin’s authoritarian system.

As this Russo-Trump alliance goes forward, no one should be surprised when Putin takes advantage. He will first go for Ukraine, where the wobbly and still-inept Kiev government could still be replaced by a pro-Moscow proxy. Without Western political and military support, it’s unlikely Kiev’s current government will survive. That will return Ukraine to the Russian camp and the status quo ante of 2011.

He will, of course, presume Bashar Assad, or his allies, remain in power in Syria. They will hardly be well dispositioned to think much of the West or its Gulf Arab allies, but in the smoldering ruins of their country they won’t have much power to cause harm.

He will hope to loosen the sanctions regime now crippling his economy and to return to the fore as Europe’s main natural resource supplier, building trade links deep into Europe.

His biggest target will be Germany. Eastern European states have a living memory of Soviet occupation that they still hate; Germans, even eastern ones, instead now indulge in an odd nostalgia for this suppressive past.

Poland, Romania and the Baltic states fear returning to Russian orbit and will take measures to prevent that. Germany, on the other hand, enjoys a buffer between it and Russian power.

Moreover, Germans don’t despise their communist past as Eastern Europeans do.

Finally, Berlin needs a steady stream of natural resources to keep its manufacturing base open: a friendly Russia is good for business.

A Berlin-Moscow alliance once spelled doom for Poland. It won’t be so dramatic this time around, but it’s not mad to presume that, in the long run, Poland and other Eastern European states will fall under pro-Russian rulers who might decide Russia, and not NATO, is key to the security of the continent.

This would undo all the geopolitical progress the US has made in Europe since 1991. To lose half of Europe yet again to Russia is to begin building a rival to the United States itself.

Allied with Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union managed to jumpstart itself to superpower status and directly challenge the US. Putin is not so ambitious. We should not presume his successors won’t be.

It will also mean the death knell for values-based foreign policy

This is the “never again” mantra of so many now-displaced Western elites. Never again Auschwitz, Rwanda, Bosnia, they mean, using Western force to save lives. In the ruins of Aleppo, in the killing fields of Darfur, in the burning villages of eastern Myanmar, in the shattered hillsides of Yemen and in the mass rapes of South Sudan, this policy already has many practical failures. You cannot police everywhere at once. But a Russo-Trump alliance doubtless means to abandon it in principle as well.

In other words: even when the West can do something, it will not.

Such values-based foreign policy also pushes for liberal republics or democracies enshrined by strong constitutions, powerful checks and balances and a respect for human rights. Putin’s Russia is a new political model: the illiberal authoritarian democracy, a thuggish state whose leadership is able to cudgel their way through politics. Viktor Orbán, the prime minister of Hungary, exemplifies how this could work in the heart of Europe: a nationalist, self-interested nation state which seeks gain above all things.

Such a state ignores refugees, famines and natural disasters unless aid to the victims directly benefits the state.

Such a state is also jealous and petty. It whips up nationalistic furor to survive, dances with war more often and crushes the individual beneath state need.

They can be effective states, especially in a time of crisis. But they are not nice places to live, nor do they have the ability to self-correct from mistakes as readily.

A Russo-Trump alliance means America’s Republicans have bought into self-interest over values. Many will argue the US has never been about values. I don’t think that’s wholly fair. The US has tried to rebuild places and support peoples solely because it believes doing so will make the world a more peaceful place.

And yet it may be that the world needs a demonstration of how much values-based foreign policy mattered. In its coming absence, the world will have ample demonstration of how much more brutish the West can be.

This article originally appeared at Geopolitics Made Super, January 3, 2017.

Sometimes understanding why some country is blowing up another, or why it’s blowing itself up, is hard. Not a lot of people make that easier. Geopolitics Made Super aims to break down foreign policy and make it more fun or, failing that, to at least make you get why one nation does something that makes you so, so mad.