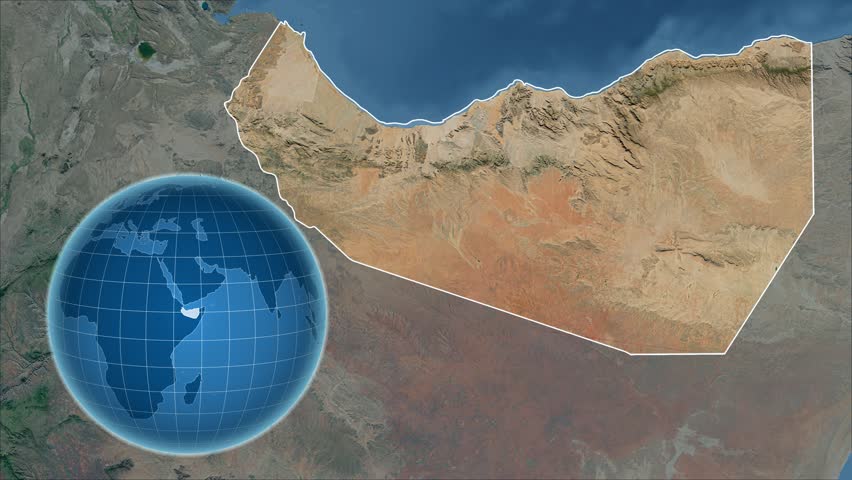

Our special envoy Sam G. travelled to war-torn Somalia in order to continue our series of articles regarding Ghost Countries. Sam’s articles are a reflection of what he saw on the ground when he travelled into Somaliland, an autonomous region in the dangerous and lawless Somalia.

In the port of Berbera, a Somaliland port city on the Gulf of Aden and opposite Yemen, which is itself in a state of civil war, has become the new location of a UAE air force base. A large investment by the government of the UAE to refurbish the dilapidated port has made this air base a possibility. The port of Berbera, provides the unrecognized state with crucial access to international waterways for trade.

Traditionally, most of the products that pass through the port are livestock which is exported to various Gulf states, although much less since the breakout of the war in Yemen. Nowadays in the

Berbera ports, there may be more asylum seekers escaping the war in Yemen than economic trade. The main question for Somaliland regarding a UAE air base on its soil is simple, will the UAE air force use it to launch attacks in Yemen from Somaliland?

The answer to that questions is still unclear. If it does choose to do so, the fear is that Somaliland will now become a target itself and risk being dragged into a regional conflict that it cannot afford to be involved in by any means. The general feeling in the country by its citizens is that they have no interest to be involved in any regional conflict at the cost of peace.

This may be what really differentiates Somaliland from its southern neighbours of Puntland and Somalia, the real desire amongst the vast majority of its citizens to safeguard peace and rule of law in the country. I was told when I was there that when someone moves to a new home in Somaliland, their neighbours will get to know them as quickly as possible. If the new resident arouses any form of suspicion by the neighbours then they will be immediately reported to the police. Although it may sound a little paranoid and extreme, this heightened sense of responsibility and cooperation with local police and security forces may be what is necessary to ensure peace within this fragile region.

Politically, the country is in the midst of finding its place on the international scale. Economically speaking, sadly, it is very weak for almost endless reasons. With an extremely high unemployment rate and the vast majority of the population, (especially male) addicted to khat, (gat, qat) the economy is burdened with large amounts of foreign currency leaving its borders daily to Ethiopia in order supply its citizens its daily fix of the African plant.

Illegal in most western countries, chewing of the green leaves is widely enjoyed in neighbouring Yemen, Somalia and Ethiopia as well. Although an important tax earner for the Somaliland government (about 20% of total taxes revenues) and a large supplier of domestic jobs, the country devotes about 30% of its annual GDP, about 534 million dollars a year to the import of the plant from Ethiopia, paid for in foreign currency. A massive burden on the domestic economy and a wide-scale epidemic of addiction to the plant leading to joblessness, the country would be far better off to criminalize it – if only they could do so without starting a revolution, and that isn’t a joke. After various enquiries as to why the plant is not grown locally, I was informed that the local climate is not suitable for khat production and of course the local water crisis, which makes such a venture all but a dream. It seems as though the government is engaged in ‘khat politics’ in its dealings with its most important ally Ethiopia, and therefore has no immediate interest to put an end to the khat imports, especially as long as they are profiting from the ba

dly needed import taxes.

On arrival to Hergeysa from Ethiopia, (one of the only ways to enter the country) flyers are greeted by a different kind of Somalia, one that is not seen in everyday news. First of all, the Somali flag is nowhere to be seen in the country, only that of Somaliland can be seen. Not only can it be seen, it’s flown from every place possible and painted on every bare spot found. The people of the region are very proud to call themselves Somalilanders and have no problem explaining that their country does in fact exist. It very well might exist, at least according to the stamp on my passport it does and the Somaliland visa I obtained prior to my arrival.

The locals are very friendly and frequently stop to greet and chat with any tourist they see, presumably because there are so few. Although the country is extremely religious with women completely covered, the local women are seen all over the streets and typically make up most of the workforce. Men in the country tend to have a much higher unemployment rate than women. Even with the highly religious nature of the country, it seems to be no problem for opposite sexes to interact with one another, in a country where alcohol is illegal because of religious laws.

Travel within the country is generally quite safe, however problematic. The ride from Hergeysa, to the port city of Berbera is one that would not take much longer than an hour in most developed nations. The poor quality of the pot-hole filled roads and the police checkpoints dotted along the way, multiply travel time drastically and takes three to four hours to complete the journey. The city of Berbera itself is one with huge natural and historical value to tourists. A historical port city with Ottoman, Arab and local Somali influences, it was largely build by traders and has not been renovated for hundreds of years. It may be one of the only places in Africa that is home to a mosque built by the Ottoman Empire and a dilapidated synagogue built by Jewish traders from Yemen, almost side by side. A few kilometres away along the beach, camels roam freely in a country that contains half of the world’s population of camels. If only the world saw Somaliland as independent from Somalia, more tourists may decide to witness the country’s beauty.