What is happening in South Sudan has happened the world over: factions fight for power with no end in sight.

This Article was written by Ryan Bohl for Geopolitics Made Super , Young Diplomats’ Partner. The original article is available here.

There are no famines anymore, unless people want them.

South Sudan is starving. As reported by Foreign Policy, the world’s newest country is also one of the world’s hungriest.

On Feb. 20, the United Nations declared a famine in parts of the country, saying that some have already died from hunger and another 100,000 people are on the brink of starvation. One million more are headed toward the same fate. “Our worst fears have been realized,” Serge Tissot, the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization’s representative in South Sudan, said in a news release.

In an age where Hobbsian scarcity has been nearly conquered, it is discomforting in the extreme to see starving children on HD video. Humans produce some 17% more food per person than 30 years ago, yet that means little to the South Sudanese.

In the cruelties of its civil war, there are key geopolitical understandings to be had in South Sudan. Why do some countries starve? How can one African country peacefully reject a dictator while another pits two democratically elected leaders into armed conflict? How much blame does the rest of the world deserve, and what does this say about the future of our species?

South Sudan: high hopes, faith in the goodness of people, and no enforcement

“Trust but verify,” goes a Russian proverb most recently favored by President Obama. It’s fine to think highly of people, but there’s nothing wrong with checking in on progress.

Alas, in South Sudan, the international community decided to merely trust, despite 19,000 soldiers and police under the UN flag.

South Sudan is everything that’s gone wrong with values-based international relations. When all you have to unite people is a hope that everyone believes as you do, there is nothing to stop bad actors from doing as they like. Nor is there anything to stop people from regressing to age-old habits.

There are some basic bullet points for why South Sudan has come to such a low point:

- No interest from great powers, leaving backbenchers to run the UN mission

- Poor development from 60 odd years of civil war with Sudan

- A liberal democracy imposed by outsiders on a human landscape ill-suited for one

- Tribalism that produces Big Men who fight to the finish for power

South Sudan operates in a geopolitical vacuum. That leaves it exposed to old human nightmares: war by starvation, conquest by brutality. These are behaviors that regions under the influence of the great powers and their institutional ideas have largely banished.

That isn’t because the great powers are naturally moral: it’s because, in the ashes of Hiroshima and Auschwitz, they learned that they had to limit how they could wage war, or else they risked exterminating the entire species.

Moral values are important in how states interact and behave, but we should not forget morals don’t last unless they empower and strengthen the elite and the states they run. When they don’t, humanity returns to older forms.

The forlorn story of South Sudan: the land great powers forgot.

South Sudan is a relatively new construct, only forged just as Great Britain prepared to decolonize Sudan in the 1950s.

That’s because the geography of South Sudan has long conspired to keep civilized powers at bay and to prevent the indigenous development of a South Sudanese civilization. Much of South Sudan is savannah, the ideal hunting ground for hunter-gathers, and the very biome where it seems likely humanity originated from.

While the exact origins of civilization are still fuzzy, they seemed to have formed only in places where the climate was just harsh enough to force cooperation between people, while rich enough in natural resources like iron, rivers, and wild, farmable plants to give them the ingredients for civilization.

Those original centers of civilization along the Indus River Valley in Pakistan, the Yellow River in China, and the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in Iraq appeared in such locations. Technology then transferred to other regions with similar qualities like Egypt, India, Anatolia, and eventually everywhere from Spain to Japan.

South Sudan does have natural resources and rivers, but the savannah biome means it has always been easy for nomadic hunter-gatherers to survive. Their mobility made it difficult for civilizations nearby to move in and hold the region; the lack of critical resources made it unnecessary for anyone to really try. Nearby Ethiopia developed a very advanced civilization, but neither wanted nor needed to hold the South Sudanese lowlands.

China faced the same problem with its Mongol frontier: open grasslands allowed nomads to raise their frontiers while resisting most attempts at conquest.

This contrasts sharply with north Sudan. North Sudan is much like Egypt, with most of its population crowded along the Nile River. When Egyptian armies went south, they found holding north Sudan a much easier job than trying to grab the savannahs. This is a key reason why north Sudan is Arabized and Muslim: as Egypt fell under Arab Muslim control, north Sudan did too. But South Sudan did not.

Until technology changed enough to conquer the nomads and their tribes.

As China put down the Mongols with firearms in the 17th century, so too did the Egyptians to South Sudan’s tribes. When Egyptian forces, ostensibly part of the Ottoman Empire but functionally independent, invaded South Sudan in the early 19th century, their usage of European-style armies allowed an outside power to at long last colonize the grasslands.

When Egypt fell to Britain, so too did South Sudan. Britain saw South Sudan as a means to an end rather than an end in and of itself: it was merely a link in the chain to build a grand empire from north to south Africa, another stop on the hoped-for trans-African railway that aimed to travel from Cairo to Capetown. This meant Britain did not put much effort into developing or institutionalizing the region, as it did other African colonies with more valuable specialized resources. Being on the Nile made South Sudan useful, but there wasn’t anything special about the colony’s resources.

Moreover, Britain didn’t think of South Sudan as anything more than the southern province of Sudan. With a larger population and bigger economy, the Khartoum-based colony functioned much like Nigeria, ruling over a diverse, very tribal population.

When decolonization kicked in, Sudan was one of the least ready to go. British policymakers understood as early as the 1920s that certain colonies would have to be developed into Commonwealth Nations if Britain were to hold onto its empire – independent domestically but part of a closed trading system that favored the UK. They focused on the richest or most advanced colonies as nation-building projects first: Sudan was near the bottom.

Which left a dearth of trained elites. When Egypt slipped from Britain’s grasp after the 1952 Revolution, Sudan became an appendage of an empire that no longer wanted it. Britain almost immediately abandoned the colony: in 1955, Sudan became independent.

And just as fast, the north and south began their first civil war. While north Sudan was united by a large, Egyptian-influenced cultural core of Arab Muslims, South Sudan was a polyglot of humanity united only by a fear of the north. British missionaries had Christianized uneven portions of society; other areas followed their old religions. While arguably there was a nation underneath the state of north Sudan, there was no such thing in the south.

Southern Sudanese tribes and elites embarked on a nearly non-stop war to break away from the Arab north. It was a war of attrition; because Sudan did not have a central role in the Cold War, neither side ever gained the support necessary to be decisive on the battleground. Then as now, the superpowers had other, greater worries than the squabbles along the Nile.

And 55 years later, South Sudan emerged onto the map.

The long back and forth civil wars, coups, invasions, and intrigue are better told elsewhere: the essential tale is that South Sudan’s elites wore down the north. When Arab Sudan fell under the sway of Omar al-Bashir, a genocidal Islamist and Arabist, South Sudan saw a door open. Bashir used up precious state power trying to create a purely Islamic Arab state. In the course of his butchering, he lost the ability to control the south.

When Omar al-Bashir began his genocide in Darfur in 2004, the international community, then in the throes of values-based diplomacy, reacted with horror and swift action. South Sudan transformed from a backwater tribal war to a noble struggle for independence from a maniac dictator, then all the vogue for war correspondents. Bashir had a clear choice: he could continue to Arabize the north through terror and violence, or he could hold onto South Sudan. He chose the former.

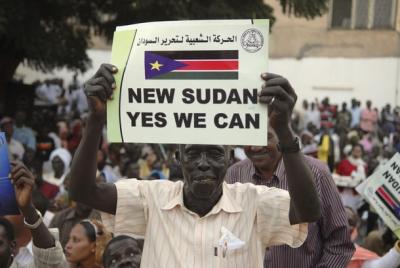

In 2011, South Sudan was shepherded into being by the international community. And it truly was international: the African Union and the United Nations were key in that aspect.

Yet what they had invented was not a nation-state, but a geopolitical blank space. Where order and purpose was once provided by the struggle against northern Sudan, now there was nothing. The long years of civil war had not wiped out tribalism, nor produced an elite capable of governing beyond self-interest. Rather, it had empowered both.

Which brings us to the crisis of 2013.

While the north-south civil war ended, South Sudan remained plagued by the age-old tribal wars typical of a savannah. As the AU and UN patted themselves on the back for saving South Sudanese from Omar al-Bashir’s murdering army, no political center of gravity emerged in Juba, South Sudan’s capital, able to control the whole country.

Since the AU/UN mission was entirely values based, nobody wanted to step on local toes and appear like a new colonizer – an easy accusation to make for any of the tribal elites who might be on the losing side of the AU/UN. The president of South Sudan, President Salvar Kiir, and the vice president, Riek Machar, began to compete in the most traditional of tribal fashions: by exterminating one another’s supporters.

When push came to shove between Kiir and Machar, they did not resort to the peaceful politics of Western liberalism, leaking gossip about one another and scheming for the next election. Instead, they resorted to the basest form of warfare.

The AU/UN watched helplessly as rape was employed as a weapon and whole villages were massacred by both sides. In 2016, some aid workers were raped by what appeared to be the president’s soldiers. The world of values-based diplomats was horrified: how could South Sudan, so recently a freedom fighter, embark upon such barbarities?

Well, barbarism is relative. For Kiir and Machar, the struggle is not about making South Sudan a “good” place to live: it’s about who lives and who dies, and who gets the lion’s share of its wealth and power. It is a primal, basic struggle, fought with all the violence necessary to win it.

And since South Sudan lacks a defense industry, it means war must be fought by other means. Those are cheap: they are rape gangs, manmade famines, and machetes. They do the same job as tanks and drones without any of the plausible deniability.

It was not so long ago that Europeans fought the same way. But advanced countries only backed off full-scale annihilation in the aftermath of nuclear weapons and two world wars. South Sudan missed those lessons: it was, after all, little more than a stopover colony. Britain did not train elites ready to displace tribalism, nor did tribal elites ever get the superpower in the Cold War support needed to provide the country with a cohesive ideology and governing structure. South Sudan was a geopolitical hole, an empty place left behind by those who might change it, as changing it would cost great powers more than South Sudan was worth.

South Sudan is the new Congo

Like the Congo, South Sudan doesn’t warrant enough attention to reorder. It will be allowed to sink into war after war as the international community busies itself elsewhere. There is no great incentive for South Sudanese tribal elites to abandon the power structures that give them leadership: why bite the social hand that feeds them? There is no outside foe that might unite South Sudanese into a new nation: even Omar al-Bashir cannot hope to storm Juba.

So instead, cycle upon cycle of violence will prevail. Left alone, this will break on its own: either some faction will grow strong enough to wipe out all the others, or several factions will tire of the war and develop enough to decide to embark upon cooperation. Remember that Rome created modern Europe by exterminating the Celts and co-opting the Greeks. It was a long and ugly process full of war, yet very human. We should withhold judgment of South Sudan’s civil war: its brutality is, after all, traditional to all our cultures.