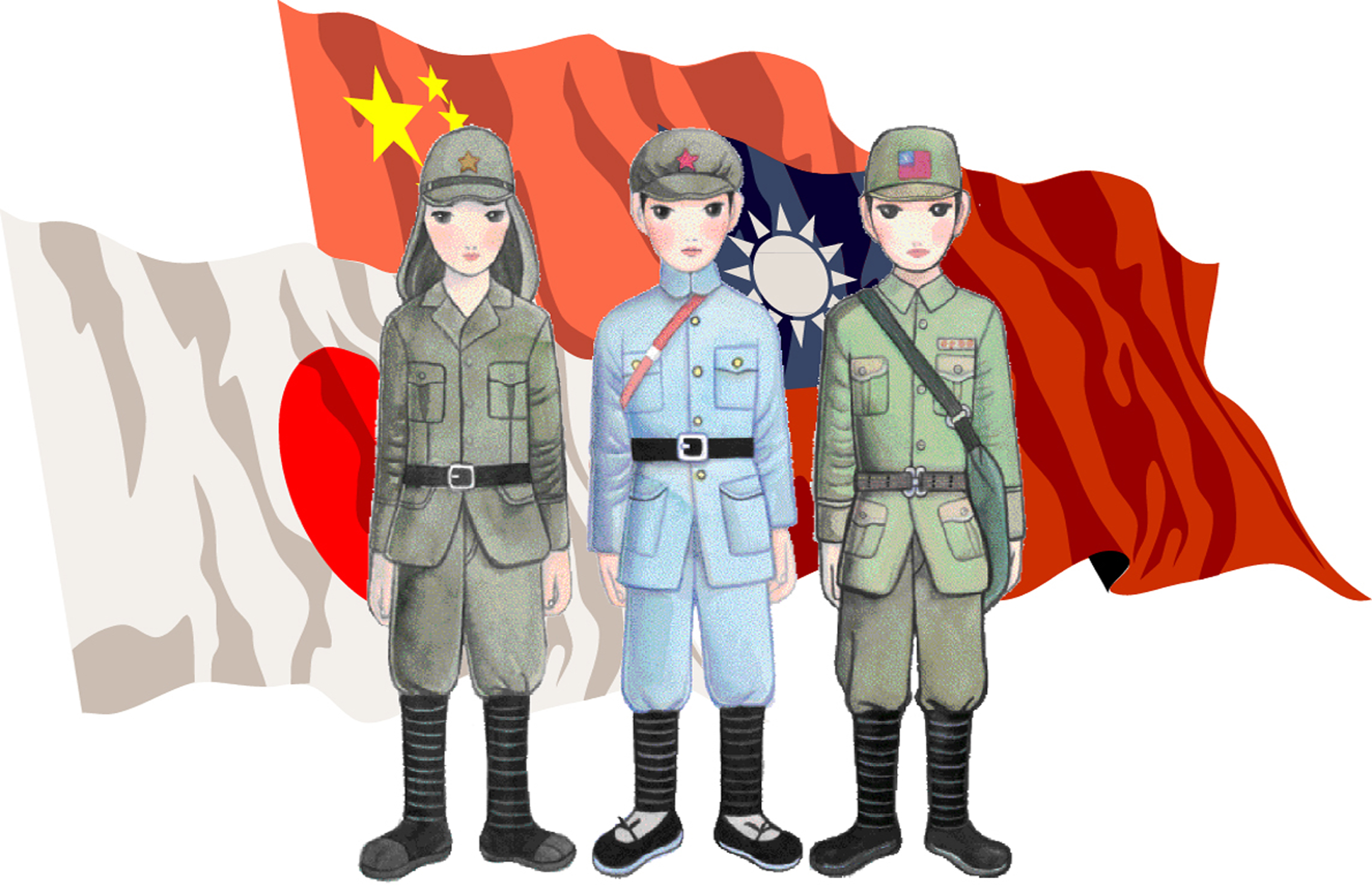

“Dogs go, pigs come,” read the graffiti-smeared walls throughout Taipei in February 1947. It was less than a year and a half since the Allies had driven the so-called “dogs” out, defeating the Japanese Empire and liberating Taiwan from 50 years of foreign rule. Taiwan now belonged to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government, the Kuomintang.

Soon after the Japanese surrender, however, Nationalist attention turned toward a different struggle, this time against Mao Zedong’s communists on the Chinese mainland. Fixated on the desire to seize power, the Nationalists afforded Taiwan scarce attention, and the resulting misrule and widespread discontent led to a massive uprising in February 1947. This came to be known as the “228 Incident,” the aftershocks of which still inform both the Taiwanese sense of identity and its relationship with the mainland.

Historically, Taiwan has played at most a peripheral role in China. The island was populated first by Polynesian indigenous groups and then in the 17th century by mainland Ming Dynasty refugees. Under the relatively weak Qing central rule it became part of Fujian province. In 1895, following Japan’s victory in the First Sino-Japanese War, the Qing Empire ceded Taiwan to the Japanese.

Distance and decades of colonial rule laid the foundations for Taiwan’s future sense of separation from the mainland. At the time of the Japanese surrender, many Taiwanese still regarded themselves as Chinese and welcomed mainland Nationalist rule as a return to the motherland. But soon they began to bitterly resent Nationalist rule, which was nearly as authoritarian as that of the Japanese colonial government — and nowhere near as honest and efficient. The “pigs,” it was said, had replaced the “dogs.”

Understanding the Japanese rule that preceded Taiwan’s return to the mainland is essential to understanding why the acceptance of Chinese rule was so short-lived in Taiwan. Japanese rule was harsh, particularly during World War II. Like Korea, Japan ran Taiwan as a colony with strict government monopolies on key commodities, including sugar, tea, rice, tobacco, minerals and oil refining. Aside from the bare minimum necessary for consumption on the island, Taiwan’s resources were exported to fill Tokyo’s coffers and to satisfy its voracious appetite for the commodities that were scarce on the home islands.

Yet things were not all bad. Tokyo sought to transform Taiwan into a model colony, modernizing and expanding the island’s infrastructure. This included the laying of thousands of miles of railway track. Literacy skyrocketed as Taiwanese children were enrolled in mandatory education through the eighth grade. Many went on to receive university education either at the Taihoku (Taipei) Imperial University or Japan’s prestigious universities — usually in technical subjects that made them productive imperial assets.

A postcard depicting the Seishiwan beach, Kaohsiung City, in Japanese-controlled Taiwan. (Wikimedia)

Many of these elite Taiwanese acculturated to Japanese values and appreciated the orderliness of Japanese rule. The Japanese built high-end department stores, frequented by both Taiwanese and the large Japanese expatriate community. While Japanese laws were harsh, they created a degree of order absent under the repressive Nationalist dictatorship that followed. Many elderly Taiwanese fondly recall a time when they could leave their homes unlocked without fear of being robbed.

A Liberation, of Sorts

When the Nationalists peacefully arrived, it was to great fanfare. The Japanese colonial administrators surrendered on Oct. 25, 1945, on what came to be known as Retrocession Day. Sick of years of war, most Taiwanese eagerly awaited the arrival of the new rulers, but they were soon disappointed. As the carefully arrayed Japanese forces marched to the docks in orderly formation, the much-touted Nationalist 70th Army disembarked from the U.S. Navy troopships that had been assigned to assist in the transfer.

Seasick, unkempt and marching in what hardly even resembled a formation at all, they were a sorry sight for the curious Taiwanese that came out to observe them. The vast majority of the Nationalist soldiers were peasants from China’s interior — the replacements of the replacements of the replacements of a once proud Chinese army unit that had suffered several times its number in casualties. Local Taiwanese laughed at the rustic Nationalist soldiers who wore sandals and stared slack jawed at the elevators in places such as the Japanese-owned Kikumoto department store.

The officers of the new Taiwan Garrison pose for a photograph on the island’s Retrocession Day, Oct. 25, 1945. (Wikimedia)

The disillusionment grew when the Nationalist plans for Taiwan became clear. The Kuomintang seized all Japanese property on the island, including factories, mines and homes. The Nationalist priority was to win the war against the Communists on the mainland, and to that end they forcefully purchased grains and other goods to send to their forces on the mainland, causing food shortages and high inflation. As was the case under Japanese rule, Taiwan’s resources were redirected by a distant government to goals that had little benefit for Taiwan.

Worse, the Taiwanese, who had hoped that liberation would bring about the political rights that had been denied them under Japanese rule, were disappointed to find that they were being ruled as a conquered population rather than as Chinese compatriots. According to Chen Yi, the Nationalist chief executive of Taiwan, the Taiwanese were politically backward for spending too much time under the inferior cultural influence of the Japanese. Chen Yi announced that the liberties guaranteed under the Republic of China Constitution of 1947 would not cover Taiwan, because the people were not yet ready to exercise political rights.

However, the great irony to the Taiwanese was that for all the lofty talk of political advancement from the Nationalist government, the Chen Yi administration was extremely corrupt and hopelessly incompetent. Public services such as sanitation broke down, as did the careful law and order maintained under the disciplined Japanese, to which many Taiwanese had grown accustomed. Pigs, it became clear, were really no better than dogs and, in many key respects, were worse. Resentment built against both the Nationalist government and the mainlanders themselves, and the ensuing events solidified this sense of separation.

The Eruption

On Feb. 27, 1947, this submerged tension once again broke to the surface. As with the outbreak of Arab Spring protests in Tunisia or Hong Kong’s fish ball riots, it started small. Plainclothes officers enforcing the government monopoly on tobacco sales arrested a woman selling black market cigarettes at a teahouse in Taipei’s Datong District. In the struggle, they pistol whipped her and shot into a crowd that formed to stop them, killing one person. The next morning, thousands of Taipei residents gathered in front of the governor-general’s office, demanding the arrest of the agents. Nationalist troops fired into the demonstrators to disperse them, killing more people.

From there, the situation rapidly spiraled out of control. Protesters took over the city of Taipei, administering it with a Settlement Committee and a civilian volunteer corps for a short period. They issued 32 demands for reform, including autonomy, elections and the surrender of Nationalist troops — demands that the Nationalist government was not prepared to meet. Taiwanese took over other cities from the Nationalists, and chaos engulfed the countryside. Angry Taiwanese across the island went about beating or killing mainlanders.

The dissent was short-lived, however. Chen Yi, the Nationalist chief executive whose corrupt administration sparked the debacle, declared the uprising a Communist rebellion and requested reinforcements from the mainland. By March 9, Nationalist troops had arrived from Fujian province, retaking Taipei and violently pacifying the countryside. For three days, anyone seen in the streets was shot. By April, the government had arrested all the leaders of the uprising and executed between 3,000 and 4,000 people. Historians put the toll of what came to be known as the “228 Incident” much higher. Many Taiwanese elite, the Japanese-trained intelligentsia, technocrats and teachers, around whom revolt could coalesce, were killed. This inaugurated four decades of what was later known as “White Terror,” in which Taiwan became a national security state ruled in large part through fear and coercion.

But this uprising in a minor outlying Chinese territory would have been a footnote in history had Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government not been defeated by the Communists in 1949. As Communist cadres under Mao rounded up the remaining Nationalist forces on the mainland, the government fled to Taiwan, clinging onto only a handful of tiny islands. In a massive exodus, 2 million Chinese from across the mainland followed Chiang to Taiwan, where they became the core of a new ruling class and once again changed the social and demographic fabric of Taiwanese society. With invasion by the Communists an even more terrifying prospect than rule by the Nationalists, the Taiwanese were forced to throw in their lot with the murderous regime that had dispatched troops against them shortly before.

While the quality of governance improved after 1947, relations between the Taiwanese and mainlander Nationalists remained uneasy: The mainlander regime did not trust the Taiwanese enough to allow them prominent political positions and reinforced their control by suspending the constitution and imposing martial law in 1949. The struggle of the Taiwanese to bring about democracy and to achieve political power took 38 years, culminating in the lifting of martial law in 1987. The Nationalist party-state fell, and several largely Taiwanese opposition parties were legalized, including the Democratic Progressive Party. From the ashes of the party-state rose one of Asia’s most vibrant democracies.

Persistent Mistrust

The Democratic Progressive Party — formerly an opposition body — has recently gone on to sweep the ruling Nationalist Party from both the presidency and the legislature. This is a demonstration of public doubt over whether the eight years of deepening economic ties with China under Nationalist Party President Ma Ying-jeou have benefited Taiwan. The electoral upset also revealed deep-seated unease, particularly with the Nationalist Party’s official support of the One China Policy, which states that Taiwan and the mainland are part of a single China. The Nationalists still maintain that Taiwan is not a distinct entity but that it is united with the mainland, which is rightly the Republic of China, ruled by an illegitimate Communist government. The Democratic Progressive Party has never accepted the idea of unity with the mainland. The appeal of the One China policy has also waned with the general public. Today, even the grandchildren of the 2 million mainlanders who followed Generalissimo Chiang to Taiwan increasingly identify themselves as Taiwanese rather than Chinese. It is an identity forged in the 228 Incident and in direct contradiction with the One China Policy.

A protester walks under a defaced photo of former President Chiang Kai-shek during August 2015 protests. (SAM YEH/AFP/Getty Images)

The memory of the 70-year-old 228 Incident, which was once a major rallying cry for the opposition, continues to inform the debate about identity in Taiwan. Across the Taiwan Strait, China is once more a single-party authoritarian state, intent on reclaiming the island as its 23rd province. The mainland wishes to reunify with Taiwan under the One Country, Two Systems model already implemented in Hong Kong that guarantees Hong Kong’s autonomy. Yet these days, this promise rings hollow. The Taiwanese see the Chinese government under President Xi Jinping cracking down on the mainland and in Hong Kong, despite the latter’s supposed autonomy. Having fought for decades to free themselves from an extraneous and autocratic mainland regime, most Taiwanese have no desire to subject themselves to increased Chinese authority — or, in their minds, to the dark days of White Terror.