Brexit has brought the United Kingdom far away from one of its most important allies in the Indo-Pacific region: Japan. Though has it? Economically, the UK has been declining in importance for Japan. Japanese investment into the UK has been stagnating, Japanese businesses have reallocated from Britain to Continental Europe, and Japan has focused on intensifying economic ties with the European Union. Yet, in the case of defence and maritime security cooperation, the UK’s relation to Japan has been gaining weight.

The UK, once the primary economic, naval, and regional power has advanced in declaring a new interest in the East Asian region. The region contains “…60 per cent of the world’s population, nine of the world’s ten busiest trading ports, and the top three economies in the world…”. Thus, it is unsurprising why the region is so important for Britain. Yet, it is not only that trade and economic reasons which drive UK’s motivation. Brexit has taken a toll on Britain’s diplomatic and political status in the Pacific – especially amongst the “P5” Pacific powers (Australia, Brunei, Malaysia New Zealand, and Singapore). It has therefore focused on rekindling its presence in the region by strengthening its ties with Japan, and vice versa.

Japanese policymakers and Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) came accordingly to the “Tokyo Consensus” – arguing that Brexit may become a “blessing in disguise”. It refers to the idea that post-Brexit Britain will be unable to identify itself with the EU, and that it will attempt to rediscover, and reinvest in, its old self-image as a great seafaring nation. And for now, British activities seem reassuring for Japan.

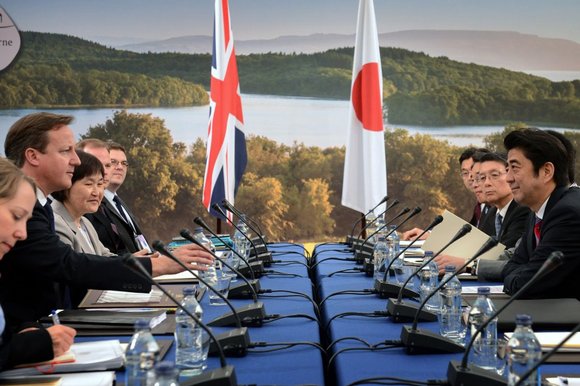

The UK and Japan regularly have “2+2” foreign and defence ministerial-level meetings. Both sides have engaged in defence equipment cooperation, such as joint research and development of new air-to-air missiles, joint military exercises between Royal Air Force fighter jets, or enhanced intelligence sharing. Both have also engaged in a joint drill by flying through the airspace in the Sea of Japan and around Taiwan. In 2016, the UK even deployed its Typhoon fighter aircraft to Misawa Air Base in Japan which was “…probably the most ambitious deployment that the [Royal] Air Force has done to the Far East”. In the future, the UK plans to deploy one of its aircraft carriers to the South China Sea (SCS) to vindicate the rule-based international order against China. For Japan, a highly welcomed move.

Japan’s location is not going to change in the coming centuries. Japan will continue to be offshore the Eurasian landmass, enclosed by water, and surrounded by rivals: Russia, North and South Korea, and China. Japan has invested more than 15 years in evolving its geo-strategic position to counter an assertive China. It has upheld international maritime rules, nurtured diplomatic relations in Southeast Asia, and conducted marine capacity-building programs. However, despite its attempt of connecting with like-minded, democratic, naval powers such as the United States, Australia, or India, Tokyo knows that none of them would interfere if a Sino-Japanese conflict erupts over the SCS or the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea. Therefore, having the UK as a potential law enforcer and political ally on its side – one which would not fear China – is comforting.

In Europe, the UK and France are the only countries which have maintained an Asia-Pacific presence. Both send their navies on a regular basis to the Indo-Pacific region, cherish their maritime identity, and are residential powers in the area. Similarly to the UK, France has re-established its ties with Japan over the last year. It has increased its presence in its territories of New Caledonia and Tahiti, and it has deployed warships and its navies in the SCS to counter China. However, British-Japanese ties date back to World War I. Britain also has more extensive military capabilities compared to France. Not only does it outnumber the French military, its “fleet in being” – referring to the capability to go whenever, wherever it wants without owning significant territory to throw off the regional military balance – is unique in its flexibility. Combined with the UK’s image as a “Gateway to Europe” for Japan, Tokyo has decided to pay more attention to its old friend and ally the UK.