Origins of the Current Crisis : Cameroon is currently in a state of internal conflict and has been since September 2017.

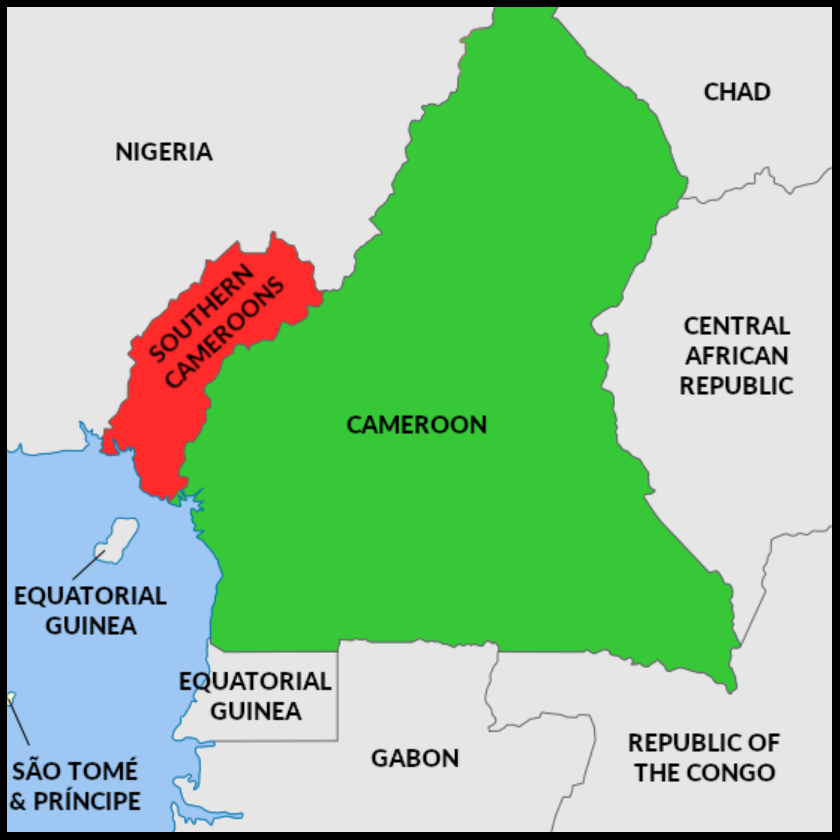

The country is divided among linguistic lines, with a large French-speaking majority and a smaller English speaking minority, near the border with Nigeria. When Cameroon declared independence, the English-speaking region was declared to be an autonomous status. However, the French leadership began to centralize power, and began taking more and more autonomy away from the English-speaking regions.

This intensified in 1982, when Paul Biya became the President of Cameroon, a position he still holds. His time as President has been marred by increased corruption, elections deemed by the international community to be illegitimate; most notably, the 1992 elections where he managed to win with only 40% of the vote (Mbaku & Takouganj, 2004).

Paul Biya, although initially supported by the Anglophone community, has maintained a close relationship with France to the point of maintaining the status quo of having the Cameroon government centralized in the Francophone region, rather than have a bilingual federated state, meaning that over time, the Anglophone region became his biggest opposition stronghold.

In 1983, the government changed the school structure to model it after the French model, rather than the British model. Furthering discontent with the English speakers of the country. In addition, he also changed the name of the country from “The United Republic of Cameroon” to “The Republic of Cameroon” in an obvious attempt to renegade the English speakers to second class citizens (Mbaku & Takouganj, 2004).

This was further exacerbated by an economic crisis that struck Cameroon in the 1980s. Although the country recovered, virtually the entirety of that recovery was felt in the Francophone region of the country, whereas the Anglophone region was left with disproportionate amounts of poverty.

Further, the English-speaking region was the area of several border disputes between Nigeria and Cameroon, resulting in a few military skirmishes between the two countries. The main center of the border dispute lies in the Bakassi Peninsula. In 2006, Nigeria formally relinquished claim over the Peninsula. This, however, was met with fierce resistance from the locals, who waged a three year long guerilla war against the government of Cameroon.

Eventually, this culminated in a series of protests in 2016, and then later, armed secessionists proclaiming an English-speaking Republic of Ambazonia (Browne, 2019).

The roots of the conflict, however, lie in more than just language disputes. It is part of a wider legacy of European colonialism, and of continuing foreign geopolitical ambitions in Africa.

Legacy of European Colonialism

Prior to European colonialism, there was no country of any kind in what is now Cameroon, Cameroon is an artificial entity created by the Berlin Conference. All artificial states have artificial identities and artificial histories to create an artificial means to

cement these identities. Cameroon is no exception.

The Berlin Conference was held in 1884 and 1885, by leading European powers. The signatories to the conference were Germany, Belgium, France, the United Kingdom, the United States, Sweden-Norway, the Ottoman Empire, Russia, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Portugal, Netherlands, Denmark, and Spain.

Some of the major goals of the Berlin Conference included abloshing slavery throughout the world, as well as to avoid a crisis over spheres of influence. The British and French were concerned by Germany’s growing ambition for overseas colonies. The conference itself is representative of the “scramble for Africa” that would characterize Europe’s relationship with Africa for years to come.

In 1884, Cameroon became a German Colony, German Cameroon was not directly governed over, due in large part for its thick natural forests and high mountains making it impossible for both armies and traders to make significant inroads into Cameroon. For Bismark, Cameroon was only a marginal investment (Ardener, 1962). Therefore, governance was largely left up to local administration of various chiefdoms. Other investments the Germans made in Cameroon include the development of roads, railroads, and most notably, schools, under the guidelines of Adolf Woerman. This education included “arithmetic, reading and writing German, Christian doctrine, and agricultural education”. The lasting impact this had on Cameroon was the unification of the various tribes into a single political entity and identity never before seen (Lekane & Asuelime, 2017) .

Under German governance, coffee production was distributed evenly among the local population. Eventually more and more people in Cameroon stopped making food crops and started making cash crops like coffee. This ultimately had a major impact on Cameroon. Prior to this, the locals were primarily subsistence farmers. With the introduction of cash crops, the economy of Cameroon began to grow, although it remained dependent on the production of coffee, as well as German colonial administration (Lekane & Asuelime, 2017).

In 1916, during the First World War, Cameroon fell to the Entente Powers. In the following treaty of Versailles, Cameroon shrunk in size, and was partitioned between the British and French. The British portion of Cameroon was partitioned into Northern and Southern Cameroon, and part of the larger British colony of Nigeria.

In French Cameroon, the French undertook a policy of assimilation, making the people of Cameroon more French than African, such as the adoption of the French language, and making the people of Cameroon subject to French law. There was, however, growing discontent between the locals and the French administration, and this culminated into armed conflict in 1955 (Ardener, 1962).

British Cameroon, by contrast, was left with full autonomous status within the larger Federation of Nigeria, however it was neglected by the British. The governance was largely left up to the local tribes, as in German Cameroon, however the locals were ethnic Efik-Ibibio, different from their Igbo neighbors in NIgeria, which meant that there were greater demands for autonomy.

This ultimately points to a difference in British and French governance over their colonies. While France had a heavy hand in the governance of their colonies, Britain largely left affairs of governance to the locals. The reason for this gap has mainly to do with the leverage that each country had at its disposal. Mainly being that since Britain was an island nation, its leverage was its navy. As such, it could not muster a standing army to muster its rule of law over all the colonies.

In order to achieve dominion over its colonies, Britain had to reform the colonies’ power structure. Britain could achieve very little direct rule outside of the capital city, and so gave local chiefs “customary law”, giving the chiefs discretionary power (Lange, 2004). This made things stable for Britain and worked to the benefit of the local chiefdoms, but it was an unstable political situation for the local population.

In 1960, the British left Nigeria, by which time French Cameroon had gained its independence. This posed a dilemma for British Cameroon. And so, a referendum was held, asking if they wished to remain part of Nigeria, or join the Francophone nation of Cameroon. While Northern Cameroon voted to remain a part of Nigeria, Southern Cameroon voted to join the new nation of Cameroon.

Following the decolonization of Africa in and around 1960, Cameroon needed to find a new way to unite its people. After all, how do you unite a people who never had been unified before? One way of doing so was through language.

In it, Cameroon began to partition between the old French Cameroon, which spoke French, and the British Cameroon, which spoke English:

“Despite these shifts towards a unified country, the Francophone and Anglophone parts of Cameroon remained under the influence of their previous colonial masters’ legal and education systems with strong attachments to their language and culture (Neba 1987; Ndobegang 2009). The legacies of the two Cameroons’ colonial past are still very much characteristic of today’s Cameroonian society polarised around Francophone and Anglophone categories or, more importantly, the dominant features of the political agenda in Cameroon, the “Anglophone Problem” (Lekane & Asuelime, 2017).

There is a difference between the Francophone realm in Africa and the Anglophone realm in Africa. In the Francophone realm, French is spoken by the wider population, with only a few exceptions. However, in the Anglophone realm, while English may be the official language, in many of these countries, the locals still speak many local languages. This points to another reality today: while Britain has no more interest in Africa, the French are determined to maintain their presence on the continent.

Role of French Ambitions in Africa

So too, is this conflict a conflict of French geopolitical ambitions. For as Jaques Chirac once said, “Without Africa, France would slide down into the rank of a third world power” (Neftchi, 2019).

There are multiple ways France implements geopolitical soft power, but one way is through language.

The French language is very different from the English language. While the English language is extremely decentralized, with London having no central hold over the Anglophone world, allowing multiple dialects and creoles of the English language to flourish, the French language is still heavily centralized within Paris. As a result, France used it as a means of reasserting itself in Africa.

Following decolonization, France began a massive undertaking in the setting up of French schools, to insure that the French language remains in Africa, while indigenous languages, such as Bambara, die.

Fortunately for France, Africa is currently in the middle of a population boom. By the end of the century, Africa will be home to the largest population of youth, with one out of every three people on the planet being African.

But this practice of using language as a form of soft power in Africa is not unique to France. In East Africa, notably Kenya, there has been a rise in students enrolled in Mandarin-speaking schools to work in factories set up by China, getting there on a railway built by the government of China(Dahir, 2019). Like France, China too wants a piece of Africa. And so France is using the French language, not just as a means of maintaining it’s hold on Africa, but as a means of keeping China out of Africa.

Aside from Language, there are other means at which French utilize power. In many of the Francophone countries, their currency, the African Franc, further divided into the Central African Franc and the West African Franc, were, for the longest time, tied to the French Franc before the adoption of the Euro.

While this worked for the benefit of the French, it did not work out so well for the African countries, so much so that Jaques Chirac once said “We have to be honest, and realize that a big part of the money in our banks comes from the exploitation of the African continent” (Neftchi, 2019)

This stranglehold on the African Franc, a continuation in many respects of French colonialism, has led to the continuous stagnation of the Francophone African economy. In addition, the continuing French presence in Africa has worked largely to benefit the local political elite, and not to the benefit of the African masses. This has meant that the Francophone realm within Africa has largely remained a source for corruption and the suppression of democratic reforms.

Current Events

Currently, the war shows no end in sight, although a unilateral ceasefire has been declared due to the global coronavirus outbreak. The Cameroon military has been accused of killing civilians, which they have denied. A total of 3,00 people have been killed during the war.

What is the politics of identity/nationhood in an artificial colonial state?

Ultimately, though, one has to ask the question: In a state like Cameroon, an artificial entity that did not exist prior to European colonialism? What are the politics of identity and nationhood? What binds a people together when they never have before? In some cases, it is language, and Cameroon is not the only one to suffer from this dilemma.

On the other side of the world, there is Canada, where the French-speaking part of Canada, the province of Quebec, has long held secessionist views, seeking to become its own country away from the larger English-speaking country. As a result, Canada is a bilingual country in its totality, where all government statements, even going down to the tweets sent out by Canadian politicians, have to be in both English and French.

Another usage of language as a form of soft power-play concerns Belarus. For much of the country’s history since the breakup of the Soviet Union, the official language was Russian, and not the native Belarussian language. Yet in recent years, the country has begun to transfer official government documents from being published in Russian to being published in Belarrusian.

This, in turn, coincides with recent Russian attempts to put more and more influence over the internal affairs of Belarus, most notably when they put a milk embargo over Belarus after they refused to recognize Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent countries.

Another example of what to define politics and identity in a nation-state concerns South Africa. It is no coicnidence that during the Apartheid era, the ruling party, the National Party, was made up almost exclusively of Dutch-South Africans, and that following the end of apartheid rule, there has since been a resurgence in Boer nationalism.

There is also another lasting legacy with regards to language in Africa. With many of these African countries, do they utilize a European language as an official language, spoken by everyone across the country, or do they instead, become a loose confederation of local languages?

In some countries, such as Kenya and Tanzania, rather than utilizing a European language, the main language is instead the local Swhaili language. In South Africa, a country that was under British rule, depending on where you speak, you can speak English, a local language, such as Tswana, Xhosa, or Zulu, or Afrikaans, a Dutch- Based artificial language spoken in the former Boer regions mixing together Durch, English, Hindi, and local African languages.

Language is another form of identity politics with which to wield state control. The Central Government of Cameroon, backed by the French, is using the French language to centralize authority and to prevent inter-ethnic conflict. The French language is used to do this, and it works not just to benefit the government of Cameroon, but also to the benefit of France, who utilize it as a form of neocolonialism, maintaining colonial influence in a post-colonial Africa.

CONCLUSION

European colonial involvement in Africa has had profound effects upon the region. Ever since the Versaille Treaty in 1918, France and Britain have left an indelible mark upon Cameroon specifically. Through establishment of schools, a legal structure, and labor incentives–the social and political environment of Cameroon was forever altered. In the aftermath, new national identities formed, but they were formed along linguistic lines: French and English. Whereas other countries suffer from inter-ethnic conflict, or inter-religious conflict, Cameroon suffers from inter-linguistic conflict. Yet, the language separatist movement utilizes a lot of the same nationalist rhetoric as ethnic separatist movement, as language is another form of identity politics.

SOURCES

Eric A. Anchibome. Anglophonism and Francophonism: The Stakes of (Official) Language Identity in Cameroon. Alizés: Revue angliciste de La Réunion, Faculté, des Lettres et Sciences humaines (Université de La Reunion), 2005, pp.7-26. Hal-02344078

“Don’t fan flames of hatred in Cameroon.” New African, no. 588, Nov. 2018, p. 34+. Gale General u=raritanvcc&sid=ITOF&xid=13525fa. Accessed 12 Mar. 2020.

Kindezi:https://www.dw.com/en/labor-unrest-in-cameroon-after-clashes-over-language-discrimination/a-36551592

Post, Washington. “Cameroon, Divided by Two Languages, Is on the Brink of Civil War.” YouTube, Washington Post,

www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=684&v=f1fUbOd_17M&feature=emb_title.

Neftchi, Shirvan. “Cameroon Is Being Torn Apart by Language.” YouTube, Caspian Report, 21 Feb. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=L6KMXsVicSw.

Neftchi, Shirvan. “How France Maintains Its Grip on Africa.” YouTube, Caspian Report, 6 June 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=42_-ALNwpUo.

Neftchi, Shirvan. “French Military Operations in Africa.” YouTube, Caspian Report, 22 Nov. 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xcx9WXqC_40.

Neftchi, Shirvan. “Is France the next Superpower? .” YouTube, Caspian Report, 19 June 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=k7Kph52MfRo.

Ardener, Edwin. “The Political History of Cameroon.” The World Today, vol. 18, no. 8, 1962, pp. 341–350. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40393427. Accessed 14 May 2020.

Lekane, Gillo Momo, and Lucky Asuelime. “One Country, Three Colonial Legacies: The Politics Of Colonialism, Capitalism And Development In The Pre- And Post-Colonial Cameroon.” Journal for Contemporary History, vol. 42, no. 1, 2017, doi:10.18820/24150509/jch42.v1.8.

Lange, Matthew K. “British Colonial Legacies and Political Development.” World Development, vol. 32, no. 6, 2004, pp. 905–922., doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2003.12.001.

O’Grady, 2019 “War of Words”, Terrence Ranger, Invention of Tradition in Colonial Africa (pg. 211) ,Kindzeka, “Labor Unrest in Cameroon”

Mbaku, John Mukum., and Joseph Takougang. The Leadership Challenge in Africa: Cameroon under Paul Biya. Africa World Press, 2004.

Malan, Jannie. “African Journal on Conflict Resolution.” African Studies Companion Online, 2019, doi:10.1163/_afco_asc_610.

Nfah-Abbenyi, Juliana Makuchi. “Am I Anglophone? Identity Politics and Postcolonial Trauma in Cameroon at War.” Journal of the African Literature Association, 29 Jan. 2020, pp. 1–18, www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/21674736.2020.1717120, 10.1080/21674736.2020.1717120. Accessed 14 June 2020.

“Cameroon Separatists Jailed for Life.” BBC News, 20 Aug. 2019, www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-49406649. Accessed 14 June 2020.

O Grady, Siobhan. “Cameroon’s Language Division Is Tearing It Apart.” The Independent, 26 Feb. 2019, www.independent.co.uk/news/world/cameroon-language-french-english-military-africa-ambazonia-a8770396.html.

Dahir, Abdi Latif. “Kenya Will Start Teaching Chinese to Elementary School Students from 2020.” Quartz Africa, 8 Jan. 2019, qz.com/africa/1517681/kenya-to-teach-mandarin-chinese-in-primary-classrooms/. Accessed 14 June 2020.

Gareth Browne. “Cameroon’s Separatist Movement Is Going International.” Foreign Policy, Foreign Policy, 13 May 2019, foreignpolicy.com/2019/05/13/cameroons-separatist-movement-is-going-international-ambazonia-military-forces-amf-anglophone-crisis/.

Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. “Who Are Cameroon’s Self-Named Ambazonia Secessionists? | DW | 30.09.2019.” DW.COM, www.dw.com/en/who-are-cameroons-self-named-ambazonia-secessionists/a-50639426.

Fichter, James R. British and French Colonialism in Africa, Asia and the Middle East : Connected Empires across the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Centuries. Cham, Palgrave Macmillan. Copyright, 2019.

Lellouche, Pierre, and Dominique Moisi. “French Policy in Africa: A Lonely Battle Against Destabilization.” International Security, vol. 3, no. 4, 1979, pp. 108–133, muse.jhu.edu/article/446264. Accessed 14 June 2020.