At this time last year, a string of leaderless resistance-style attacks by grassroots jihadists in the West was making people very nervous. And their concern was understandable: In late October 2014, the tempo of attacks by grassroots jihadists in the West reached its highest point in history. The spike in activity largely stemmed from a statement made by Islamic State spokesman Abu Muhammad al-Adnani a month earlier, urging individuals in Western countries to:

“… single out the disbelieving American, Frenchman, or any of their allies. Smash his head with a rock, or slaughter him with a knife, or run him over with your car, or throw him down from a high place, or choke him, or poison him.”

The wave of violence continued through the end of 2014 and into 2015, as assailants struck Australia and France in December, followed closely by the Charlie Hebdo Attack in Paris in January and the Copenhagen attack in February. But since that time, it has become clear that the momentum of the attacks has slowed, and that grassroots jihadists have not been able to keep up a consistent tempo of striking multiple times each month. In other words, the violence taking place in October last year was an anomaly, not the start of an emerging trend. The question is: Why didn’t the movement gain more traction?

The Limited Appeal of Jihadism

At least some of the reduction in violence can be traced to stepped up law enforcement efforts to identify potential attackers and disrupt plots. But it is also becoming increasingly clear that, the Islamic State’s appeal has its limits, and after an initial spurt of dramatic growth, the group seems to have reached its pinnacle. Now, the market for its ideology has hit a point of saturation, and its recruiting attempts are becoming less and less successful.

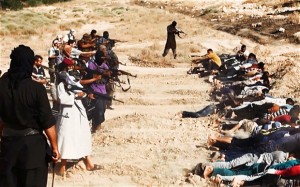

This is not to say that the jihadist ideology, or even the Islamic State’s version of it, will disappear anytime soon. Jihadist insurgencies and terrorist attacks will persist for the foreseeable future, albeit at a slower tempo. However, the factors that led to the Islamic State’s stunning rise in popularity last year — the group’s territorial gains, its successes against authorities, and its propaganda — are starting to wear out. Much of the group’s appeal lay in its portrayal of itself as an agent of apocalyptic Islamic prophecy. The Islamic State wasn’t just talking about the end of times; it was actively working to make it happen.

There are other ways the group’s diminishing appeal is making itself known. In addition to the slowing tempo of grassroots attacks, many reports have surfaced in recent months of the Islamic State arresting and executing its fighters as traitors when they try to leave the group’s territory and return home. The days of the “five-star jihad” that promised lavish lifestyles to new recruits are clearly over, and many of the foreign fighters who traveled to Syria and Iraq have become disenchanted with the Islamic State — especially because many of the people they are fighting and killing are other Muslims.

A recent remark by FBI Director James Comey highlighted this trend when he said that fewer Americans are attempting to travel abroad to join the Islamic State. Of course, some of the decline could be explained by officials’ efforts to make travel more difficult, but the key thing to note is Comey’s phrasing: He said fewer people are attempting to travel to join the group, not that fewer people have successfully traveled there. There also has not been a corresponding spike in attacks by Islamic State supporters who may have been prevented from traveling, or a spike in arrests of people trying to travel to Islamic State-held territory. Clearly, the group’s appeal has waned among American Muslims since last year, and many of its remaining supporters appear to be losing their zeal to be arrested or killed during an attack in the West.

Exposing the Islamic State’s Vulnerability

Prior to the U.S.-led coalition’s bombing operations over the past year, the Islamic State seemed to be invincible as it gobbled up large portions of Iraq and Syria. The media’s coverage of these conquests only added to the hype as it portrayed the group as far more powerful than it actually was. The Islamic State’s battlefield successes, coupled with the media limelight, played right into the group’s apocalyptic propaganda that the end of times was near, and that it would triumph and conquer the world. To Muslims seeking a transcendent cause, the Islamic State’s message held great appeal.

But since that time, the coalition’s bombing efforts have significantly degraded the Islamic State’s capabilities, even if they have not destroyed the group entirely. As a result, it has stymied the Islamic State’s spread, as has the human geography of the region, and the group has not seen much success beyond Sunni areas. In fact, in many areas, such as northern Syria, coalition air power has played a decisive role in helping forces such as the Kurds push the Islamic State back from key border crossings. While smuggling in and out of Islamic State territory still occurs, the volume of goods and people crossing the border is undoubtedly far less than it was when the Islamic State controlled strategic areas around it.

By halting the group’s advance and destroying its military units, the coalition has also helped curtail the Islamic State’s biggest supply of resources: the homes, farms, business, goods and people that do not belong to the group, as well as the taxes levied on conquered citizens. This type of logistical model is severely undermined once conquerors can no longer acquire more territory to rape and pillage to support the areas already under their control.

And make no mistake, controlling territory requires resources, especially in large cities the size of Mosul. The rulers of such cities must provide services, utilities, food, water and security for the population, all while guarding against any threats from locals who are unhappy with their rule. So while many have noted that the Islamic State is “the richest terrorist group in history,” they must also account for the vast economic drain that comes with holding and governing the amount of territory the Islamic State has, on top of the financial toll its war efforts are taking.

The Draw of Apocalyptic Ambitions

The Islamic State’s brutal rape and pillage strategy has not alienated all of its potential recruits. For many in the region controlled by the Islamic State, they have no other choice but to support the group or die, and often few other career opportunities exist. But beyond these captive supporters, there are still many who have volunteered to support the caliphate experiment because of its transcendent purpose and because the idea of approaching the final days is so powerful that it can override any qualms about how the end is to be achieved. If you are fulfilling an apocalyptic prophecy, does it really matter that you murdered, raped and robbed?

The Islamic State’s end goal is powerfully appealing to jihadists around the world, and even beyond to many non-jihadist Muslims. The opportunity to bring about an Islamic prophecy is exciting, and Islamic State leaders truely believe what they are preaching. The group’s barbaric actions prove that its leaders genuinely subscribe to their apocalyptic vision and do not care about possible repercussions. Their doctrine has an especially powerful pull among marginalized individuals who tend to flock to cults, gangs and radical groups, as we can see not only in the young fighters and brides traveling to Syria but also in the grassroots jihadists conducting leaderless resistance-style attacks in the West.

The powerful appeal of apocalypticism can influence people to do unthinkable things. In the past, we have seen followers of the apocalyptic cult Aum Shinrikyo try to kill millions of people with biological and chemical weapons. Members of the Branch Davidians gave their daughters to David Koresh as brides and fought to the death to keep him from being arrested. Followers of the Heaven’s Gate cult committed suicide in the hope of getting onboard the UFO hiding behind the Hale-Bopp Comet, and members of apocalyptic Christian cults have sold all their possessions in preparation for the foretold second coming of Jesus Christ that never came.

These historical examples point to the major limitation of groups that embrace apocalypticism: They lose their appeal when their predictions fail to materialize. When the second coming of Jesus did not take place in 1832, 1878, 1914 or 1975; when chemical attacks against the Tokyo subway system did not usher in the end of the world; and when David Koresh did not rise from the dead after three days, the organizations promoting such claims quickly became less attractive and began losing their ability to recruit new members.

This doesn’t mean that the Islamic State’s appeal will disappear overnight. But as the group’s offensive operations are thwarted, as its economic engine stalls, and as the events it waits for do not come to pass, people will become increasingly disenchanted with its ideology. There are still Aum Shinrikyo and Branch Davidian supporters in the world, just as some of those who are invested in the Islamic State’s ideology will continue to support the group until their final breaths. Once a person has sacrificed so much for a cause, it becomes hard to let it go. But as the clock continues to tick and the world continues to spin, time will ultimately undermine the apocalyptic ideology of the Islamic State.

This article was written by Scott Stewart.