By Philip Bobbitt

I don’t envy the officials in Washington who are tasked with forming a plan to resolve, or at least mitigate, the crisis in Syria. Like the punch line of the familiar old-timer from Maine’s reply to the perplexed tourist from the city, “well, if I was going there I wouldn’t start from here,” it really doesn’t advance things to say — as I have found myself saying — that the time for action was three years ago.

Syria, whose population is less than 23 million, has more than 7.5 million internally displaced persons. One in every four refugees in the world is a Syrian. The United Nations estimates that more than 200,000 persons have died in the conflict; the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights claims that figure is over 320,000.

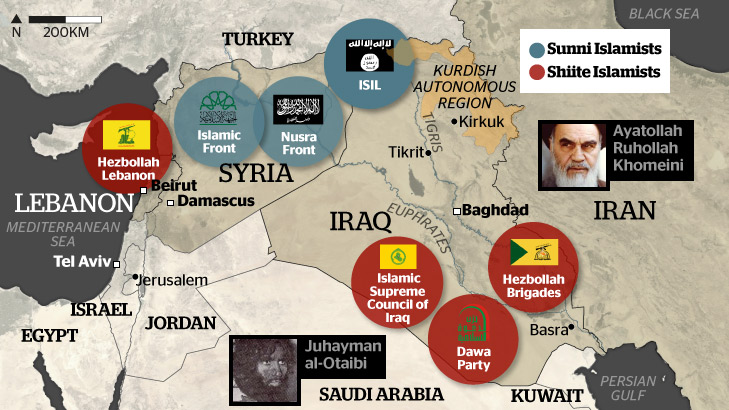

Currently, the United States has four main options. One is to try to contain the conflict and stand aside, which in light of Russian aid to the Syrian regime would crush the popular opposition and eventually end the civil war. A second option is to arm the opposition, especially the transborder Kurdish fighters, with more effective anti-aircraft and anti-tank weapons backed by U.S. airstrikes, while acquiescing to Saudi Arabia’s arming of the al-Nusra Front and its jihadist allies. A third possibility is to tacitly align with Iran and Syrian President Bashar al Assad’s regime in the destruction of the Islamic State. The final option would be to intervene with a coalition including Turkish and U.S. forces, as well as other militaries, striking directly at Damascus and terminating the regime.

The first of these options would be a historic embarrassment for the administration whose “red lines” the Syrian government has so studiedly crossed; nevertheless, embarrassment is seldom a justification for prolonging a deadly civil war. Indeed, some critics think this is one of the lessons of the United States’ involvement in Vietnam.

The second option would prolong the civil war, perhaps even increasing the mass depopulation of Syria with all its consequences for human suffering. At least thus far, it seems unlikely that opponents of the regime aligned with the United States could effectively hope to hold enough territory to force a negotiated peace. Indeed, the longer the war continues, the more momentum accrues to the most retrograde and anti-Western insurgents. Arming the Kurds would also enrage Ankara and Baghdad.

The third option is at least consistent with what seems to be a long-term bet on Washington’s part of an eventual rapprochement with Tehran. The relative youth of the Iranian population, its level of education compared to those in neighboring states, and a consistent trend in public opinion among the educated and the young that favors closer ties with the United States all seem to encourage this bet. Against such hopefulness, however, we must consider that strategic success by Iran’s military forces and theocratic regime is unlikely to lessen their grip on power.

The last option would plunge the United States once again into an open-ended commitment in which it finds itself arrayed against forces that are currently warring with each other. It is not impossible to imagine the “exit strategy” demanded by commentators; in all likelihood, it would amount to a partitioning of the country and some sort of negotiated cease-fire, the policing of which need not require U.S. ground forces. But at least as likely would be an ignominious withdrawal forced by a disillusioned and frustrated American public, making this option the riskiest of all because of its potential domestic consequences. The possibility of armed clashes with Russia would only add to this risk.

Reframing the Issue

Facing such unpromising choices, the wisest course is often to reconfigure the problem. I remember the popular cartoon strip of my youth, Pogo, drawn by Walt Kelly. Few of my readers will remember those brilliant satires, but something of their narrative structure lived on in Charles Schulz’s Peanuts and its ensemble of characters. In Pogo, as in Peanuts, the chief character was an earnest, rather gullible straight arrow whose basic decency was often thwarted by the complexities of a small but diverse world. At Pogo’s side was his friend Albert. (I should add that Pogo was a sober, sensitive possum and Albert was a rather louche alligator, both always depicted standing upright with human accoutrements.) In the strip I wish to recall for you now, the two friends are playing checkers. Albert is wearing a velvet smoking jacket and chewing meditatively on a cigar. Suddenly, in a frenzied triumph, Pogo jumps all of Albert’s checkers, wiping them from the board. The alligator is aghast; the cigar drops from his mouth. But then he recovers his poise. He reaches into his smoking jacket and pulls out a hand of cards. “I got a straight flush! What have you got?”

So I propose that we stop looking at this question as a problem of the Middle East; of course it is that, but it is not just that. More important than any of the United States’ assets in the Middle East is the North Atlantic alliance. A refugee crisis of unprecedented proportions, at least in the decades since World War II, is shaking NATO countries to their constitutional foundations. A NATO ally, Turkey, has encountered its own troubles: the Islamic State has attacked it, Russian fighter planes have invaded its airspace, Syria has shelled its villages and its borders have witnessed the worst scenes of war-torn refugees seen since the Yugoslav Wars. In the past two weeks, surface-to-air missile have locked onto Turkish aircraft flying in domestic Turkish airspace. The situation cries out for the United States and its NATO allies to send aid of all kinds to protect a member of the alliance, to relieve the onward pressure of refugee migration to other allies, and to help alleviate the burden on Turkey.

The problem is that Turkey is no longer the repository of our hopes for a progressive democracy among Muslim states. Indeed, the quest for a democracy seems to have destroyed the secular basis of the state. As a result, Turkey’s president has supported the very Islamic State that now attacks his country and appears to be responsible for the Oct. 10 massacre in Ankara. He has broken off negotiations with the Kurds, even though they are the most effective fighters in the region who, like the United States, oppose both the al Assad regime and the Islamic State.

In this situation, the creation of safe zones along the Turkey-Syria border offers a different kind of option. The United States has years of experience enforcing no-fly zones in the region with considerable success. The problem, as we saw at Srebrenica, is that safe zones must be enforced by regular ground troops or they will become killing fields. Air power alone, which can enforce a no-fly zone, cannot protect a safe haven. A NATO force including Turkish, American, British and French troops could effectively establish such a zone for refugees. It’s only a beginning, and that is to say, something as troubling as it is promising.