The adoption on 26 January, a new Constitution has caused a political détente in Tunisia. Questions concerning the status of women, the role of the sacred, to freedom of conscience being decided by that text, the major economic tradeoffs could dominate public life. But on these issues then, the major parties are struggling to define their strategy. The Question is asked by YD : What Future for Tunisia in these conditions?

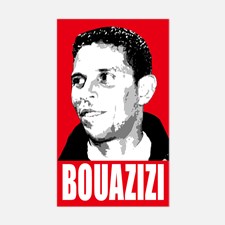

Since the Arab uprisings have known happy developments, nor in Egypt or Syria, or Libya, Tunisia became the region a refuge for those who seek a reason to hope. No social aspirations behind the uprising in December 2010 are satisfied. But after a long political crisis, the country, which grazed the worse with the murder of two leftist leaders last year (1), has recently adopted a new Constitution, approved by two hundred deputies on two hundred and sixteen, and a national unity government of technocrats. Tensions have dropped a notch, a state of grace is installed.

Opponents of the Islamist Ennahda feared they would become embedded in the state apparatus, laying the foundations of a new dictatorship. Ultimately, they have left office peacefully as they had got, politely asked to “disengage” from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Algeria, Western countries (including France), the largest union central , employers, the revolutionary left, the center right, the League of Human Rights …

Without doubt they have bowed to pressure after realizing that their record was unpromising and report adverse international forces of political Islam, weakened in Turkey and forcibly ousted Egyptian president. New elections must take place in Tunisia “before the end of 2014” (Article 148 of the Constitution). Revolution is no longer on the agenda. But the country can recover to believe that he will succeed in building its haphazard in an Arab world where such food is highly sought.

Does this mean that the integration of Islamists into the political system was a winning bet? Yes, from the point of view of those who promised their arrival at the head of the state would not mean a trip without return ticket. But yes also to their enemies, who had expected that once in power they will demonstrate their identity and religious obsession, their economic and social deprivation. “With them, quips Mr. Hamma Hammami, spokesperson of the Popular Front (left), one is before Adam Smith and David Ricardo. The political economy of the Muslim Brotherhood is the annuity and parallel trade. This is not production, not creating wealth, not agriculture, not industry, this is not the infrastructure, not the reorganization of education to serve the strategic goals – economic, scientific, technological. ”

Their “development model”, in the words of Ennahda electoral program in 2011, in fact often comes down to a row of empty phrases: “create new markets for our goods and services,” “simplify procedures” “diversify investments to more useful projects” … Common places embellished with incantations to “revive the virtuous values from the cultural and civilizational heritage of the Tunisian society and its Arab and Islamic identity, which honor the effort and quality work, encourage innovation and initiative “(2).

Mr. Houcine Jaziri, which belonged to the last two Islamist firms, admits: “The weakness of Ennahda, is the economy. We were more locked in moral issues. Someone in our ranks too political, not enough economists. The others have much work these issues we. “He nevertheless said:” We were lucky integrating a government having to think about it. ”

Which is never a bad idea … However, for three years, most of the parties, not just Ennahda, have bothered to anything else. “The tumultuous political period that we have just experienced, notes the economist Nidhal Ben Cheikh, was marked by the discussion of topics relatively taboo in Tunisia – religion, belief, sacred, sexuality, homosexuality, the role of the woman. The foundations of our economic policy have however never been discussed, let alone challenged. Result, the governorates [provinces] which were the cradles of the revolution, the political and social upheaval, Kef, Kasserine, Siliana, Tataouine, Kebili, still suffer from a lack of local production boggling (3). ”

The main opponent of the Islamist party, Mr. Beji Caid Essebsi, also ruled Tunisia after the fall of the regime of Mr Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. Instead of taking advantage of its popularity and the general enthusiasm of the first months (“Jasmine Revolution”, etc.) to scan the liberal policies of his predecessor, he preferred to surround himself with orthodox ministers who have extended the model previous economic, praised by the IMF (4). Result: Mr. Caid Essebsi today notes that “in some areas, marginalized for a long time because we cared much of maritime showcase, there was no improvement.”

Since 2011, no one has actually broken with the choice to insert the country in the international division of labor by offering foreign investors a skilled workforce and paltry wage costs. However, for lack of a self-reliant development, driven by public investment, fed by local demand insolvent, this model can only perpetuate glaring regional inequalities. The risk that the informal economy and smuggling flourish (devouring the way tax revenues), the state backward, jihadist cells enjoy. “The United States, the singers of neoliberalism, have helped nationalize banks [during the 2008 crisis], while Tunisia, in a revolutionary period, the revolutionary gestures is prohibited,” laments Mr Ben Cheikh.

“A country that respects itself pays his debts”

Meet successively Mr. Rached Ghannouchi, leader of Ennahda, and Mr. Caid Essebsi, founder and president of Call for Tunisia (Nidaa Tounes) confirms this lack of programmatic audacity. A priori, everything opposes the two veterans who dominate the politics of their country. The secretariat of the first is cluttered with photographs showing the officers or Islamist intellectuals (Tariq Ramadan, former Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, etc.) and with the Emir of Qatar. The office has the second single theme Habib Bourguiba (5), represented both as a bust, large poster on the wall and small framed photo on the desktop. Or Bourguiba would be condemned to death Mr Ghannouchi, who then felt that the “supreme combatant” founder of modern Tunisia, had committed “war against Islam and Arabism (6).”

When analyzing with them the major economic issues, the differences between the two men are far less clear-cut. Example, the repayment of external debt contracted by the regime of Ben Ali and partly hijacked by members of his clan? “The debt is talked about, but it is not catastrophic, as we are less than 50%, says Mr. Caid Essebsi. Others, like France, have ratios of 85% (7). “Anyway, he precise- immediately,” a country that respects itself pays its debts, regardless of his government. Since independence, Tunisia has never failed. ” That is almost word for word what Mr. Ghannouchi told us yesterday: “Tunisia has long tradition to repay its debts. We will stand it. ”

Debt service is an onerous burden for a poor country; this is the third budget item 4.2 billion Tunisian dinars in 2013 (8). But the General Compensation Fund (CGC), it represents the second 5.5 billion dinars in 2013. Everyone would like to lighten the weight; nobody really knows how. And, on this point too, the Islamists and their opponents is hardly distinguished. We understand their caution: the subject is explosive.

System to subsidize food and energy, the GSC was created in 1970. Since then, the surge in world prices of oil and grain has paid expenses disproportionate levels. The IMF continues to demand reduction, until the disappearance of the compensation mechanism; political parties fear inflation and revolution if they follow this kind of advice …

Far from representing a social conquest, the GSC, reminds us Mr. Ben Cheikh, had as main objective to make a liberal politically sustainable strategy to encourage industry by providing him a cheap labor force. To attract investors, Tunisia has accepted that the national budget finances part of the current consumption of their workers and employees. In sum, for over forty years, for lack of a good salary, the men and women who work, for example, in the textile sector, or engineering industries, could buy flour or the subsidized gasoline.

And all the others … In restaurants and hotels, the pasta and semolina served to tourists are subsidized gasoline consumption of large displacement Libyan is subsidized, energy (often imported) used Portuguese and cement Spanish is subsidized. “It’s a burden, admits Mr. Ghannouchi. We have to find a reasonable solution, not because of pressure from international institutions but because the expense can not be sustained at this level. “Mr. Caid Essebsi says the same thing:” Now we have reached a critical point. It is better to revise the budget to support other priorities. ”

But how to reallocate spending GSC towards productive investment in inland regions without harming immediately to the most disadvantaged Tunisians, that the state does not know otherwise help? When addressing the subject (because in the press …), employers, unions, Islamists Nidaa Tounès show a wait. They denounce abuses without proposing any remedy. Asked about the possibility that a government removes one day the fund, Ms. Wided Bouchamaoui, President of the Tunisian Union of Industry, Trade and Handicrafts (Utica), the employers’ organization, we firmly replied: ” Never! There would be a riot in the country. No political force would not dare do that. “She also says immediately:” It’s not our request. ”

Two thirds of the grant concern fuel. Now, Mr. Houcine Abassi insisted, President of the Tunisian General Union of Labour (UGTT), “most of the unemployed and employees do not have a car. They do not benefit from compensation paid for energy. And when the members of the middle class have a vehicle with a motor of four or five horses, they pay their gasoline at the same price [1.57 dinar per liter] as those who have several luxury cars in the same family “.

Remains to be able to distinguish from each other if, for example, we want to stop subsidizing the endless stream of limousines billionaires who Refueling … “That, we replied Abassi is the responsibility of government. We have proposals, but we are a union; we are not the state, with its resources, its experts, its design offices. To him to seek a strategy. ”

The Popular Front has developed a detailed business plan. This includes both the recruitment of officials in the Finance Ministry in the fight against fraud and smuggling, a 5% tax on net earnings of oil companies, the suspension of the payment of the external debt service pending audit, the redevelopment of the tax schedule to promote low incomes, the abolition of banking secrecy. But when it comes to the GSC, boldness is less noticeable. “Everybody admits Mr Hammami, knows he must not touch the compensation fund. “Discreetly, the government begins to trim subsidies, particularly on fuel position. And everyone looks away.

Decisions of leaders, activists doubts

That is to say towards the next elections. Politically, the suspension of consecutive clashes with the new government meant that the fight continued, but otherwise. The current consensus is based on a precarious balance of forces. The future alliances drafts anticipate unknown election results. Mr. Ghannouchi argues from this uncertainty and regional instability to convince his base, often dubious, correctness of its reconciliation strategy. Considering the country “too fragile for a government and opposition face it,” he wishes now that future elections lead a “coalition government with everybody or, if this is not possible, with the maximum of parties, but also civil society, trade unions, employers’ associations. Ennahda would. ”

Facing him, Mr. Caid Essebsi seems in a strong position. The training he leads is certainly eclectic, mixing bénalistes networks and progressive or trade union activists (the secretary general of Nidaa Tounes, Mr. Taieb Baccouche was General Secretary of the UGTT), but it occupies the central place on the political spectrum. For one, the Islamist party is demanding a national unity without exclusion. On the other hand, the Popular Front wants to counter what Mr Hammami called “despotic Ennahda danger” by extending its joint action with Nidaa Tounès. That will choose the latter? To hear Mr. Caid Essebsi detailing his role in the success of a “consensual solution” with Mr. Ghannouchi, while it covers praise the current government “supported by all political forces,” we imagine that it would prefer that the foundation of the next ministerial team is equally wide. And does not reject the Islamists in the opposition? “It depends on the elections, ‘he says. But we will accept the election results. ”

“Nidaa Tounes was afraid allied with Ennahda, admits Abdelmoumen Belanes, deputy general secretary of the Workers Party, member of the Popular Front. Westerners believe that two great forces exist and that stability requires that they combine. “But fear that Islamists inspired to the left has in no way abated. “Since its founding, the tactic of Ennahda has always been the same, says Mr Hammami. Where there is resistance, it recedes. Where there is sagging, it against attack. But the goal remains to Islamize to impose the line Muslim Brotherhood, both retrograde, despotic and dictatorial. “The strategy recommends that follows from the diagnosis: it is necessary to extend the anti-Islamist alliance with Nidaa Tounès highlighting Democratic priority; we must explain that the realization of this priority imposes social emergency measures; must finally bet that all “democratic” forces “agree on the need to alleviate the impact of the economic crisis for the masses.”

But, asks Michael Ayari, a researcher at the International Crisis Group, think that the basis, what do the militants? Those of Ennahda, who saw their party agree to leave power without losing the election? Those Nidaa Tounès, whose president does not rule to govern with the Islamists under the delighted eye of the IMF? Those of the Popular Front, called to defend democracy by company bosses and former bénalistes? Party leaders concoct their alliances, anticipating the distribution of posts, reassure their donors. Political balance ensues. It is reasonable, enviable, even in a region beset by convulsions. But how long will he last so, three years after the “revolution”, economic and social choices that have triggered so imperturbably continue to be renewed?