In January following the assassination of Iranian General Qassem Soleimani, the Iraqi parliament voted unanimously for the removal of the remaining U.S. troops in the country. The non-binding resolution was encouraged by Shiite political factions outraged by the killing of Iran-backed militia leader Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis in the same airstrike.

The resolution was subsequently passed without minority Sunni or Kurdish lawmakers present. However, Iraqi-U.S. relations have improved since the selection of a new prime minister in May, Mustafa al-Kadhimi. This selection came about after a leadership vacuum plagued Iraq for four months, following Adil Abdul-Mahdi’s resignation in November 2019. As the country’s former intelligence chief, Kadhimi has good relations with U.S. officials but emphasises his desire to take back sovereignty from foreign powers.

On June 11 the United States and Iraq began strategic talks covering the future of the 5,000 U.S. troops in Iraq and the economic situation following a collapse in oil prices and the developing Covid-19 pandemic. Iran-backed forces in Iraq have been applying pressure for U.S. military withdrawal through relentless shelling of the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad.

The U.S. have an important decision to make on how to withdraw troops from the region without undoing years of hard work since the U.S. first began engaging in Iraq in 2003. However, as conflict between U.S. and Iranian proxies accelerates a path toward two alternatives is developing; all-out war or a fast US withdrawal.

Here, I will briefly outline what I perceive to be the outcomes from the U.S. choosing to either withdraw, partly withdraw or remain in Iraq.

Firstly, the option to withdraw U.S. troops from Iraq would avoid further conflict and all-out war in the region with Iranian proxies. However, this undermines the U.S. efforts to counter Iranian influence in the region. The U.S. acts as a counterweight to Iran and once withdrawn would expose an economically hurt Iraq to the more powerful Iran. The increasing Iranian presence is likely to spark yet more protests against foreign interference following protests in October 2019, resulting in the death of 420 Iraqi protesters and the resignation of prime minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi. Furthermore, the U.S. has held an important role in training and funding Iraq’s counterterrorism service. Peter Neumann, the founding director of the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation claims this service is “multi-ethnic and largely incorrupt”. The U.S. withdrawal from the region would lead to this counterterrorism service being merged with the Shiite Iranian-backed militias also fighting ISIS. Without the funding and training towards counterterrorism from the U.S. there is the possibility of an ISIS resurgence in Iraq and with it a threat to U.S. national security.

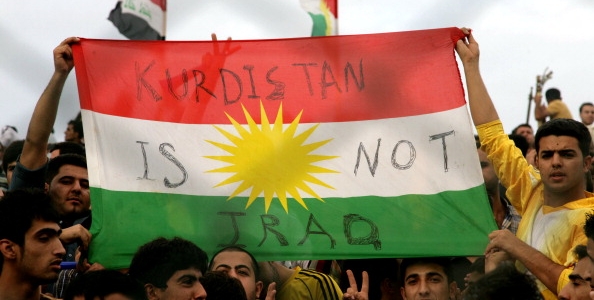

A second approach to U.S. withdrawal from Iraq would be to transfer troops to military bases in the autonomous Kurdistan region in the north, at the request of the Kurds. The presence of US forces acts as an insurance policy for Sunni’s and Kurds against a rejuvenation of ISIS and help to strike a balance between all Iraqi religious sects and political powers. Galip Dalay, a fellow at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs noted that a U.S. withdrawal would mean that “the Kurds would be more at the mercy of the militias, Iran and the central government”. This option would likely relinquish Iraq’s ability to resist Iran and so surrender the majority of Iraq to Iranian influence in the same way as in the previously explained option. In addition, would U.S. bases in Kurdistan afford the Kurds the strength to apply pressure in disputed regions, leading to increasing tensions between Kurdistan and the ceded pro-Iran Iraq region?

Moreover, the U.S. may choose not to withdraw and remain a presence in Iraq but levy significant economic sanctions on Iran leading to a defunding of the militias in Iraq. The U.S. policy of “maximum pressure” imposing economic sanctions on Iran, has led to an inflationary recession in the country and the Iranian currency to fall two-thirds of its value. Despite food and medicine being exempt from sanctions the lack of Iran’s access to the global financial system has led to shortages in these necessities. Although the sanctions are failing to bring Iran back to the negotiating table or trigger unrest in the country and an overthrow of the regime, the sanctions are successfully cutting funding to Iran-backed militias in Iraq. Earlier this year the new commander of the Iranian Quds Force, Esmail Ghaani, had to substitute the usual cash handouts to Iraqi militias for silver rings. The reduction in funding has led to divisions emerging in the Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF), the umbrella group of mainly Shia fighters. Could economic sanctions on Iran lead to a breakup and loss in cohesion between the Pro-Iran factions responsible for attacks on U.S. forces?

The final option occurs where the U.S. does not withdraw from Iraq and the U.S. are unable to sufficiently thwart Iran economically leading to a continuing of the current status quo of retaliatory conflict in Iraq between militias and U.S. However, is it impossible to conceive of a “hot war” between the U.S. and Iran in the future if tensions rise and the Iranian regime is not brought to its knees? Despite the U.S. comparatively dwarfing Iran militarily with the U.S. military budget being over 57 times larger than Iran’s, the challenges of increasing competition with Russia and China makes conflict with Iran unappealing. Therefore, if the U.S. were to maintain their presence in Iraq, they should do so by continuing with the small force currently stationed there focused on training and support of the Iraqi Security Forces.

Of the options discussed here I would suggest maintaining the U.S. presence in Iraq with a focus on avoiding conflict and training Iraqi Security Forces. By staying in the region the counterweight the U.S. holds against the increasing Iranian presence in Iraq and against the rejuvenation if ISIS is maintained. Furthermore, the insurance the U.S. provide to minority groups is not threatened and conflict is not heightened by moving U.S. troops to the Kurdistan region.