Forecast

- Mexican organized crime groups will continue to exploit Mexico’s energy industries despite recent government efforts to stop the theft.

- Among Mexico’s various crime groups, organizations in the Tierra Caliente region will increasingly be the primary perpetrators of fuel theft.

- The expansion of Tierra Caliente-based organized crime into territory historically controlled by Tamaulipas-based groups will introduce more security threats to Mexico’s energy sector.

Analysis

Mexico’s energy reforms are opening up its oil and gasoline markets to foreign firms. But any companies entering the country will have to deal with the growing risk of fuel theft, as a mounting number of criminal organizations illegally tap pipelines or intercept trucks carrying finished gasoline. Fuel theft has long existed in Mexico, but whereas it was once a crime committed largely by individuals and small, localized groups, over the past decade it has transformed into a hugely profitable business for drug cartels looking for new sources of income.

With the expansion of organized crime into the business, fuel theft has ballooned. Every year since 2007, more illegal taps siphon hydrocarbon products, primarily diesel and gasoline, from the pipeline network of state-owned Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex). There were an estimated 3,500 illegal taps on Pemex pipelines between January and August 2015, compared with about 2,300 during the same time period last year and with 1,700 in 2013.

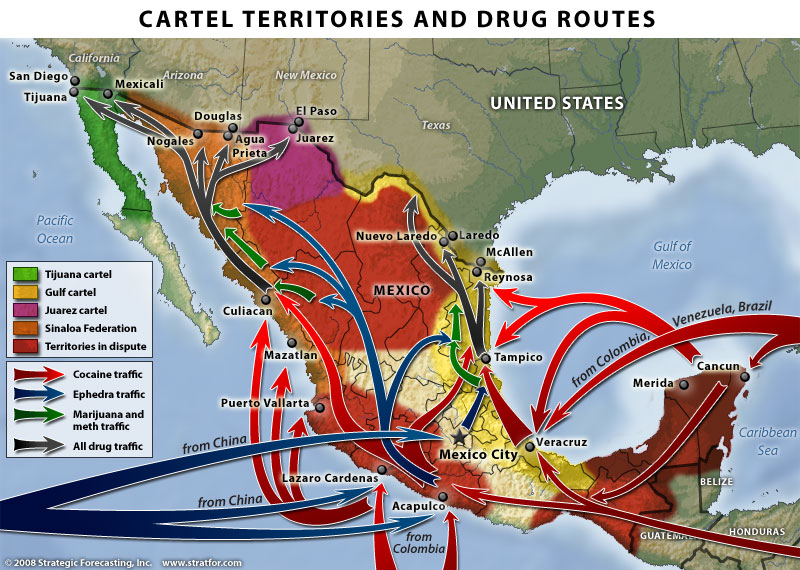

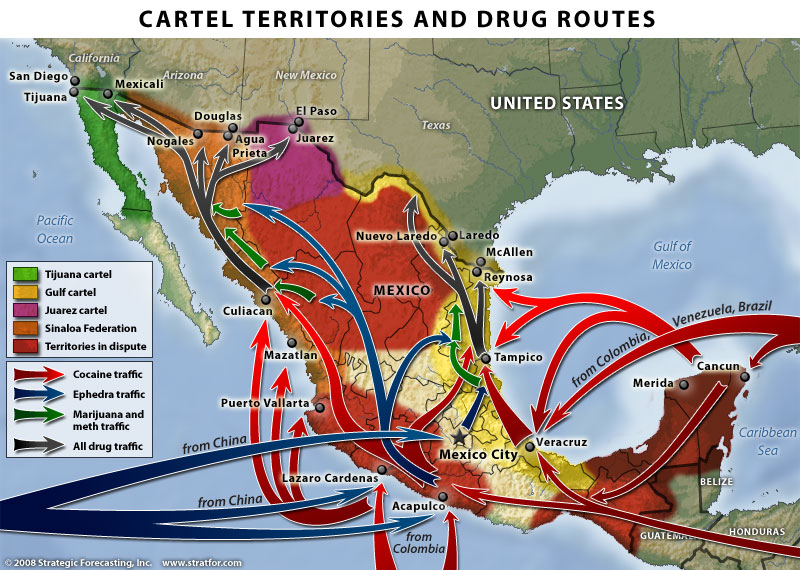

This rise is in part attributable to decentralization in the Mexican drug trade. Whereas the illicit narcotics industry was once dominated by a few immense cartels that controlled numerous franchises throughout the country, now a growing number of smaller, independent groups have arisen, each laying claim to a more limited share of the market. This has not only led to fierce and sometimes violent competition for territory but has also pushed crime groups to diversify their sources of revenue. Along with human trafficking, kidnapping and extortion, fuel theft is another source of income for groups operating in a highly competitive environment. It is also highly profitable: According to the Mexican Association of Gas Station Owners, stolen fuel makes up 30 percent of the 200 million liters of gasoline sold each day in Mexico. And at roughly 6 pesos per stolen liter, organized crime grosses 360 million pesos ($21.7 million) daily in stolen fuel.

The High Cost of Fuel Theft

Illegal tapping of pipelines certainly cuts into corporate profits. In 2014 alone, illegal tapping cost Pemex about $1.16 billion, and that year Pemex announced that it would invest $228 million into improving its ability to detect illegal taps throughout its pipeline system. To deter theft and the purchase of stolen fuel, the company began to implement new measures in February 2015, including phasing out the transportation of finished gasoline through its pipelines. Using unfinished gasoline in vehicles can seriously damage engines. By transporting unmixed gasoline to distribution centers and adding the final additives at the end of the process, Pemex hoped to deter thieves. However, that fuel theft has only increased this year suggests organized crime groups are still finding ways to steal finished fuel.

The entrance of foreign energy firms into Mexico’s energy market will introduce a new variable. The same cartels that currently exploit Pemex infrastructure will likely go after foreign companies as well. The threat will be particularly pronounced for firms that invest in the energy retail market — which Mexico plans to liberalize in 2017 — because organized crime has a substantial stake in the supply of stolen fuel in those markets.

Beyond its economic cost, fuel theft also presents Mexico with a host of security concerns. Theft often leads to corrupt officials, pipeline explosions and leaks and, most significantly, violent conflict over territory. Seeing the potential for huge profits from access to the pipelines, criminal groups frequently clash for control of those areas.

Indeed, the expansion of organized crime into this particular brand of criminal activity is already breeding conflict in the southern states of Veracruz and Tabasco. There, Los Zetas operations became the target of frequent attacks in 2014, likely by a substantial internal rivalry or by a competing major crime group such as Cartel de Jalisco Nueva Generacion or the Velazquez network. Puebla and Gunajuato states have also experienced turf wars. On Aug. 5, the bodies of two men with gunshot wounds were discovered on a ranch near Salamanca, Guanajuato state; authorities believe the killings were linked to fuel theft. Then on Sept. 28, a group of gunmen dressed in military attire killed a fuel thief in Tepeaca, Puebla state, by setting fire to the truck carrying the victim and two others, who survived.

Combating Organized Crime

In 2014, Mexico City stepped up its efforts to fight organized crime, in part to combat security threats to oil and gasoline. Much of Pemex’ infrastructure is located in areas where Tamaulipas-based groups control most of the organized crime. Therefore, groups such as Los Zetas, the Velazquez network, and various Gulf cartel gangs have been responsible for most of the country’s fuel theft in recent years. In May 2014, the military deployed troops to Tamaulipas in response to rising violence in the south of the state and has since had some success capturing or killing crime bosses. In March 2015, troops captured the top leader of Los Zetas, Omar “Z-42” Trevino Morales and several of his colleagues.

But control of the fuel tapping industry may be shifting away from Tamaulipas-based groups, which are suffering from persistent internal rivalries and have lost some territory to groups affiliated with Tierra Caliente-based crime, one of the other major players in Mexico’s illicit drug trafficking industry. If Tierra Caliente-based crime expands its reach, particularly in Veracruz and Tabasco, it will likely take over the fuel theft activities once conducted by Tamaulipas organized crime.

In fact, states seeing the greatest upticks in discovery of illegal taps during 2015 have, with the exception of Tamaulipas state, been those largely dominated by Tierra Caliente crime groups. Guanajuato state, for instance, discovered 555 illegal taps between January and August compared with just 240 during the same period in 2014. In Puebla state, illegal taps more than doubled during the same period. The increase was more moderate, but still striking, in Jalisco state, where the number of recorded illegal taps rose to 362 in 2015 from closer to 200 the previous year. These are all areas dominated by Tierra Caliente-based criminal organizations such as Cartel de Jalisco Nueva Generacion.

A Multi-Faceted Problem

Despite the government’s efforts to quell the practice, fuel theft in Mexico will likely become even more common over the next year. Rivalries between crime groups will continue. And while escalating conflicts between competing cartels are partially a function of decentralization and of fiercer competition generally between independent groups, the primary driver of conflict is the expansion of the Tierra Caliente-based franchise. Wherever Tierra Caliente-based crime expands, fuel theft will likely also increase.

Regardless of which cartel predominates, illegal gasoline siphoning poses a serious challenge to Mexico’s government. Reforms to the energy sector compel Mexico City to protect its infrastructure and to create a safe environment for foreign firms. Military operations alone, while effective, will not be sufficient: The government also needs to root out corruption among employees and state officials working in the energy sector. But a lack of resources will hinder Mexico’s ability to effectively secure its pipelines. With weak public security institutions and a limited number of federal troops, the country will have as much trouble curbing fuel theft as it does alleviating drug trafficking.