BY: KATIE DOBOSZ KENNEY

On February 15th, 2018, Jacob Zuma resigned from the office of president effective immediately, a position he has held since 2009. Over the past year, Zuma’s approval rating sank to an all-time low of 18%– he faced increased scrutiny by opposition parties for corruption, and barely survived a vote of no confidence in August 2017. His resignation came at the urging of his party, the African National Congress, to step down. The following day, Cyril Ramaphosa was elected by parliament to serve as interim president until the 2019 elections. The change in power was greeted by celebration from the ANC and cautious optimism from opposition parties eager to remove Zuma from power.

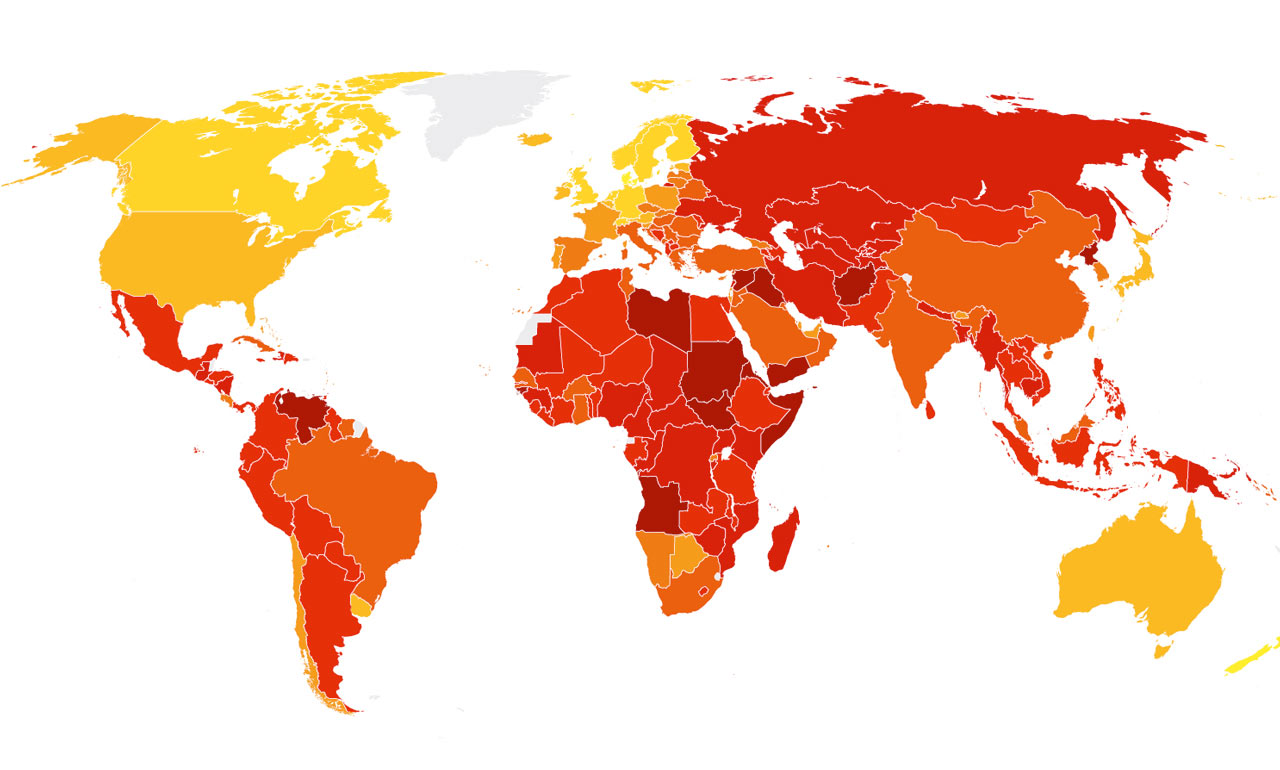

Effectively combating systemic corruption has been a failure of the South African government for years. Even out of office, Zuma still faces close to 800 charges of corruption, and as recently as last week, the government went after Zuma’s affiliates, including the Gupta business family for their long suspected influence over government contracts and political appointments. Widespread civilian discontent of government corruption has boiled over into protests over the last two years, including the clothing and textile labor unions and university students in the Fees Must Fallmovement. South Africa remains one of the most economically unequal nations in the world while over 7 million of its citizens are HIV positive. President Ramaphosa promises to end the era of state capture and to work with opposition leaders for the good of the South African people. But will we see much of the same corruption and in-fighting even with new leadership? Ramaphosa, the ANC, and the oppositions’ track record make it seem likely that the status quo will continue.

The deputy president since 2014, Cyril Ramaphosa was a devout labor unionist in the anti-Apartheid movement and founder of the National Union of Mineworkers in 1982. After being passed over for the position of deputy under Nelson Mandela, Ramaphosa became involved with the Black Economic Empowerment program, from which he benefited greatly. His net worth is now approximately $700 million; but it is wealth generated through his firm and Shanduka’s questionable investment in union-active industries like mining. At best, Ramaphosa’s corruption is limited to profiting from this conflict of interest. At worst, it implicates him in the murder of 34 miners during protests against the NUM’s perceived support of mine owners over laborers. Despite charges linking him to the incident being dropped, many still suspect his guilt, including opposition leader Julius Malema, with whom Ramaphosa is now supposedly dedicated to working with.

Julius Malema founded the Economic Freedom Fighters in 2013 after being ousted from the ANC for his incendiary personality and divisive viewpoints. Malema espouses a racially-leaning populist agenda, including nationalizing the mining industry. He was found guilty of hate speech against white South Africans in 2011 and charged for inciting violence in 2017 for encouraging black South Africans to take over unoccupied land. Though his fervor and personal mission to remove Zuma from power has gained Malema popularity, the EFF only earned 8% of the vote in the last election.

The largest opposition party, the Democratic Alliance (DA) has unfortunately functioned almost exclusively as a watchdog to the ANC’s political and financial corruption, a position to which they will hold steadfast even under Ramaphosa, according to party leader, Mmusi Maimane. Seen historically as the party of white South Africans, the DA has struggled to gain widespread support of the majority black population – a perception emboldened by the fact that it took until 2015 for the DA to elect its first black leader.

Presumably, inter-party feuds are far from resolved with Zuma’s departure, and in these fights, the South African people stand to lose the most. Unemployment consistently reported at around 27%, but when speaking with citizens of Kliptown and Soweto in June 2017, historically two of the poorest neighborhoods in South Africa, they expressed that many South Africans believe the rate to be much higher.

Additionally, Cape Town is about to become the first modern city to completely run out its water supply. The countdown to “Day Zero” or the day the city will officially run out of water is likely to occur sometime between April and June of 2018. Severe austerity measures are currently in place, limiting residents to approximately 6.5 gallons of water per day for everything from bathing to cooking.

Nelson Mandela would likely not recognize this South Africa from the one he liberated in 1994, and the citizens’ blatant cries for the South Africa of Madiba seem to have fallen on deaf ears. May the end of Jacob Zuma’s reign be the first step toward healing and a word of warning to Ramaphosa and his contemporaries who choose to neglect the will and well-being of South Africa.

Katie Dobosz Kenney holds an MS in Global Affairs from New York University with a concentration in Peacebuilding. An educator for almost 10 years, Katie had developed global and peace education curricula in Florida, Mississippi, and Timor-Leste. Katie currently works as a graduate program administrator at NYU’s Center for Global Affairs and has co-lead study abroad programs to South Africa and the UAE.